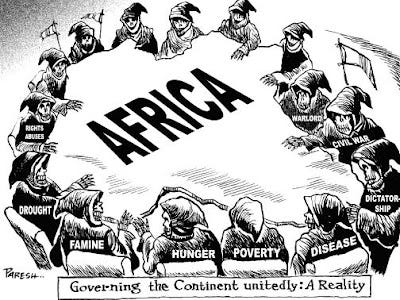

Africa's needs determine its patrons

America and Europe's roles narrow while those of Russia, China, and India grow

Images of Africa today vary greatly. China and India spot huge future labor and consumer markets that will naturally accompany the continent’s demographic dividend now in the works and peaking mid-century.

Russia, bottom-feeder that it is under Putin, sees only opportunities to replace the US and Europe as a mini-Leviathan-for-rent for various regimes as they turn rightward and boot the “neo-colonialists” out (France taking a licking as of late).

Europe, aping America’s take on Latin America, sees mostly the threat of migrants, driven increasingly desperate by climate change, and so it spends money — quite cynically and in certain instances with great malevolence — on North Africa states, buying their disposal duties.

WAPO: With Europe’s support, North African nations push migrants to the desert

Expect the inevitable scandals and cover-ups on this sort of activity in the years ahead.

As for America, we still view Africa largely through the GWOT (Global War on Terror) lens, which drove us to stand-up Africa Command years back to formalize and institutionalize our head-hunting activities there.

This remains our essential difference with China, explored in America’s New Map:

In a world teeming with insurgencies, great powers reach for counterin- surgency strategies. Some, like Russia (in Chechnya, Syria, Ukraine) or Saudi Arabia (Yemen), use brute force—they make a desert and call it peace. In contrast, the United States prefers to swoop in, take out the bad guys, and leave (the Powell Doctrine). Then there is China, which is all about creating facts on the ground—one infrastructure project at a time. America prefers its crisis- oriented, quick-fix interventions because they fit our default unilateralism and short attention span. The Chinese prefer a crisis-avoidance, long-term investment approach because it fits their ideology of noninterference. Washington has a hard time recognizing Beijing’s strategy because it is so counterintuitive to our emergency-responder mindset.

After 9/11, America became obsessed with homeland security. As for threats beyond, we turned to our tried-and-true method of power projection, sending overwhelming military force to destroy them at their source. Our top-down approach is to eliminate bad actors and, on that basis, secure the environment. Do we succeed? Not really. As soon as we leave, somebody new steps in, picking up that gun—and the fight. The roster of “we got him!” super-villains is long (e.g., Noriega, Hussein, Qaddafi, Bin Laden, Baghdadi, Zawahiri); the list of countries we fixed is not.

China approaches the challenge in a bottom-up fashion. The Chinese point to their history of subjugation by outside forces as reason both to fortify their perimeter and to consider that fortification entirely insufficient. Sensing themselves vulnerable to globalization’s dangers, Beijing seeks to create and enforce safe zones at home and across the world. These heavily sensored safe zones are digitally enforced (e.g., CCTV cameras, location tracking, contact tracing, facial/mood recognition, biometrics, AI). Beijing tracks its citizens like Amazon monitors warehouse workers—invasively surveilling every single human action to systematically judge its potential threat to the state (or, in Amazon’s case, to productivity). It is the reduction of individuals by algorithms into controllable cogs within a high-performing system—a process of dehumanization first flagged by Karl Marx in his searing critiques of capitalism but far more frequently found in dictatorships than in democracies.

Unsurprisingly, given this correlation of superpower forces, American strategists, looking at Africa today, see America losing the superpower brand war.

AMERICAN SECURITY PROJECT: The U.S. is Losing the Great Power Competition in Africa

The U.S. has recently been stepping back from its involvement in Africa after protests and officials in several African countries asked the U.S. to leave. In Niger, protesters called for the removal of American troops from the country as the government revoked its military cooperation deal, resulting in the likely loss of a six-year-old air base. In Chad, a letter from the Chief of Air Staff implicitly threatened to end its security agreement with the U.S., leading to the withdrawal of Special Operation Forces and 75 other personnel. These two withdrawals mark a broader shift in the region away from Western nations and towards Russia and China. The loss of these countries as partners, as well as the U.S. military bases located there are serious blows to counter-terrorism operations in the region.

These withdrawals are also a significant concern for key mineral imports, as investment and engagement in Africa helped to strengthen America’s mineral supply chain. Currently, the U.S. is almost 100 percent reliant on “entities of concern”— mainly China. The increasing importance of minerals such as cobalt, graphite, and manganese, has led to global competition over African resources. Meanwhile, Russia and China both have used predatory mining practices to extract these key minerals.

Despite their destructive interference, China and Russia have risen above the U.S. in popularity in the region, a significant injury to American soft power in the region. Outlook on Russia and China has increased because of their willingness to trade in arms and in material support at levels at which the U.S. has thus far been unwilling to engage. In March, the head of U.S. Africa Command warned Congress of Russia’s expanding influence in Africa, primarily through disinformation campaigns and its Wagner mercenary group in such countries as Mali and Burkina Faso. China has also been expanding its influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, a development plan to bring more countries under Chinese influence.

Naturally, this shift is being captured and codified in polls:

GALLUP: U.S. Loses Soft Power Edge in Africa; China's popularity grows, while United States' wanes

A new Gallup report shows median approval ratings of Washington -- indicative of the country’s soft power -- slipped from 59% in 2022 to 56% in 2023. Of the four global powers asked about, the U.S. was the only one not to see its image improve across Africa in 2023. Meanwhile, China’s approval in the region rose six percentage points, from 52% in 2022 to 58% in 2023, two points ahead of the U.S.

This tracks well with influence data as presented by Pardee Center and cited by me in my second MOOC (Massive Open Online Course):

The explanation:

The observation:

The Pardee measurement method clearly downgrades Russia because most of its influence peddling is non-official.

Now, to The Economist piece that triggered this post:

ECONOMIST: The Africa gap (special reports - jan 11th 2025) — The economic gap between Africa and the rest of the world is getting wider, says John McDermott

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.