Branded House (China) versus House of Brands (United States)

A thought exercise that "might" work for you

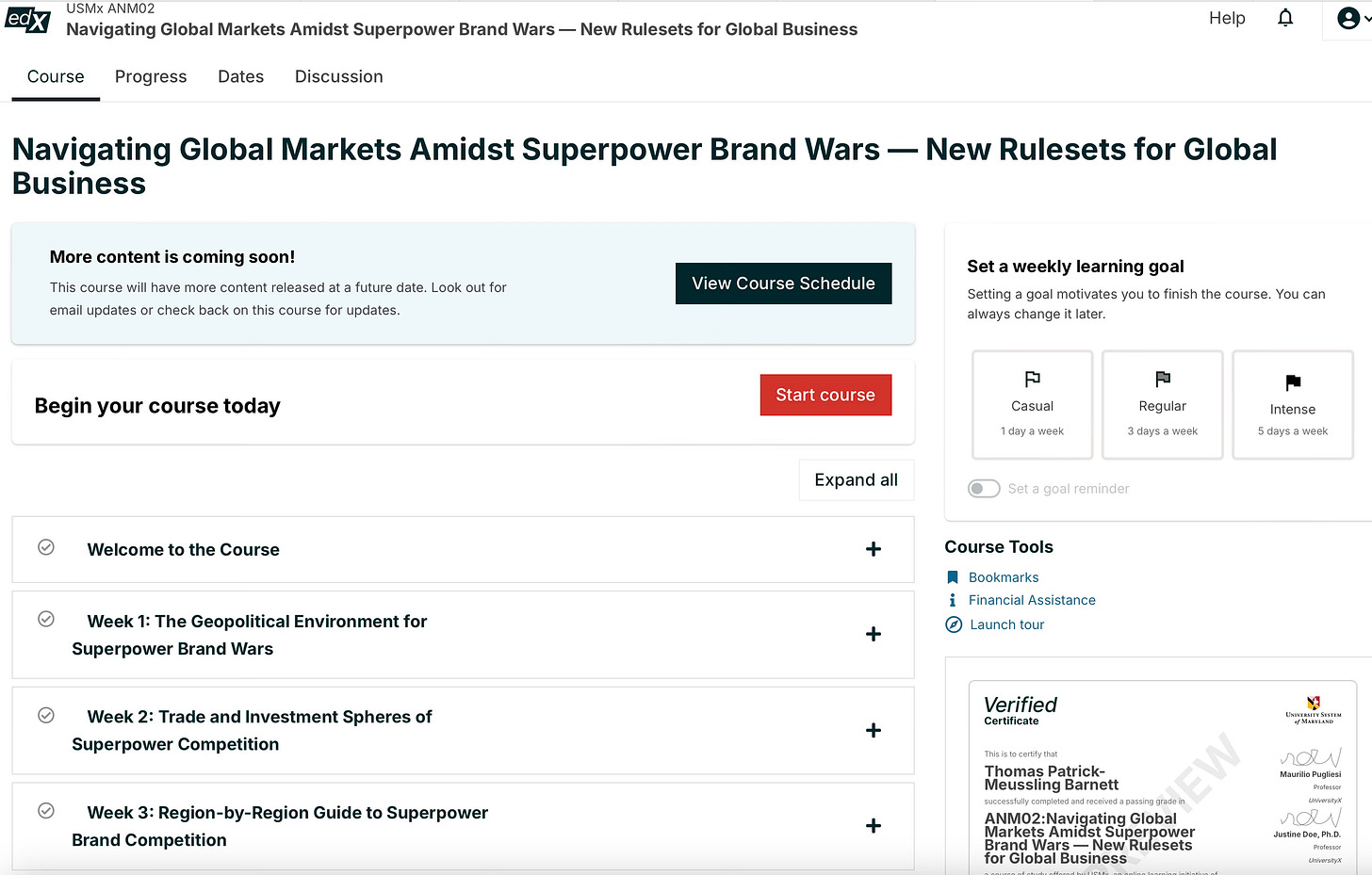

Spent yesterday afternoon collaborating with John Clay Elliot Johnson of U Maryland on our second Massive Open Online Course entitled, Navigating Global Markets Amidst Superpower Brand Wars: New Rulesets for Global Business. It’s the second in a series (curriculum) that we’re building on edX, the first one being Superpower Grand Strategies: Winning the Great Game of Globalization (already up and operating with students from 59 countries and first place going to those 25% hailing from India [US about 15%, EU about 10%, and then 56 other states making up the other half]).

The first MOOC was basically America’s New Map as a course. The second one is a segue from my new analysis of how the five superpowers (US, EU, Russia, India, China) are competing across the world for economic opportunity and ideological influence. So, basically, five competing across eight world regions (N. America, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East/North Africa, Europe, Former Soviet Union, S. Asia, and E. Asia).

My portion of the course consists of 18 short lectures (all taped and in post-production) spread across three “weeks” (self-paced). John, my collaborator and author of many business-oriented MOOCs, then fills out weeks 4 and 5 with marketing and brand strategy analysis that expands upon my geopolitical and geo-economic material up front.

The course should be up and available within a couple of weeks, and I will announce that when it happens.

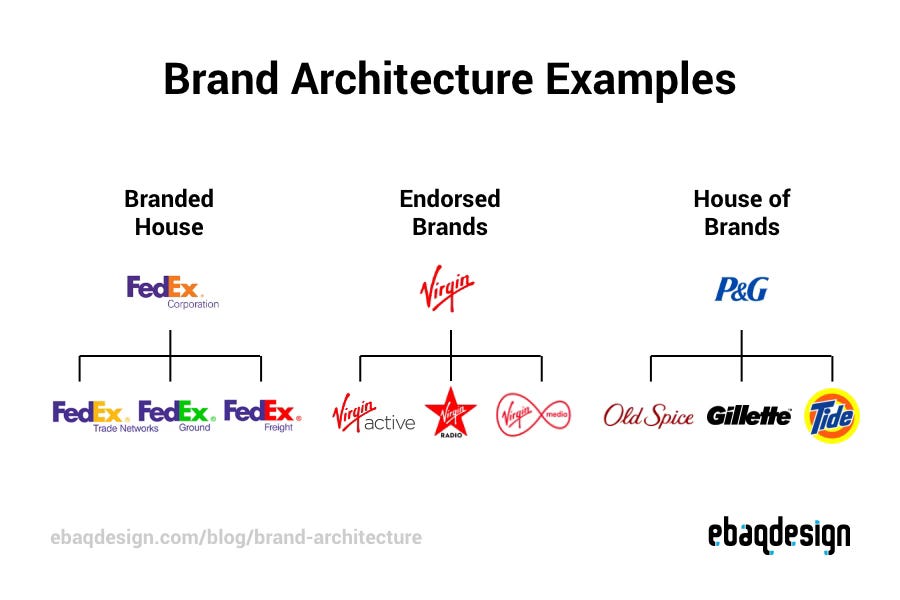

Today, I just wanted to note a distinction that I found very interesting in John’s material: the House of Brands approach versus the Branded House. I became fascinated by the difference because it struck me as encompassing the differing ideological appeals of the US (House of Brands) and the PRC (Branded House) as they compete across the Global South this century (China far more aggressively, the US more defensively/lethargically).

So, first, let me explain the basic difference between the two approaches, each of which offers unique advantages and challenges influencing how products are marketed and perceived by consumers.

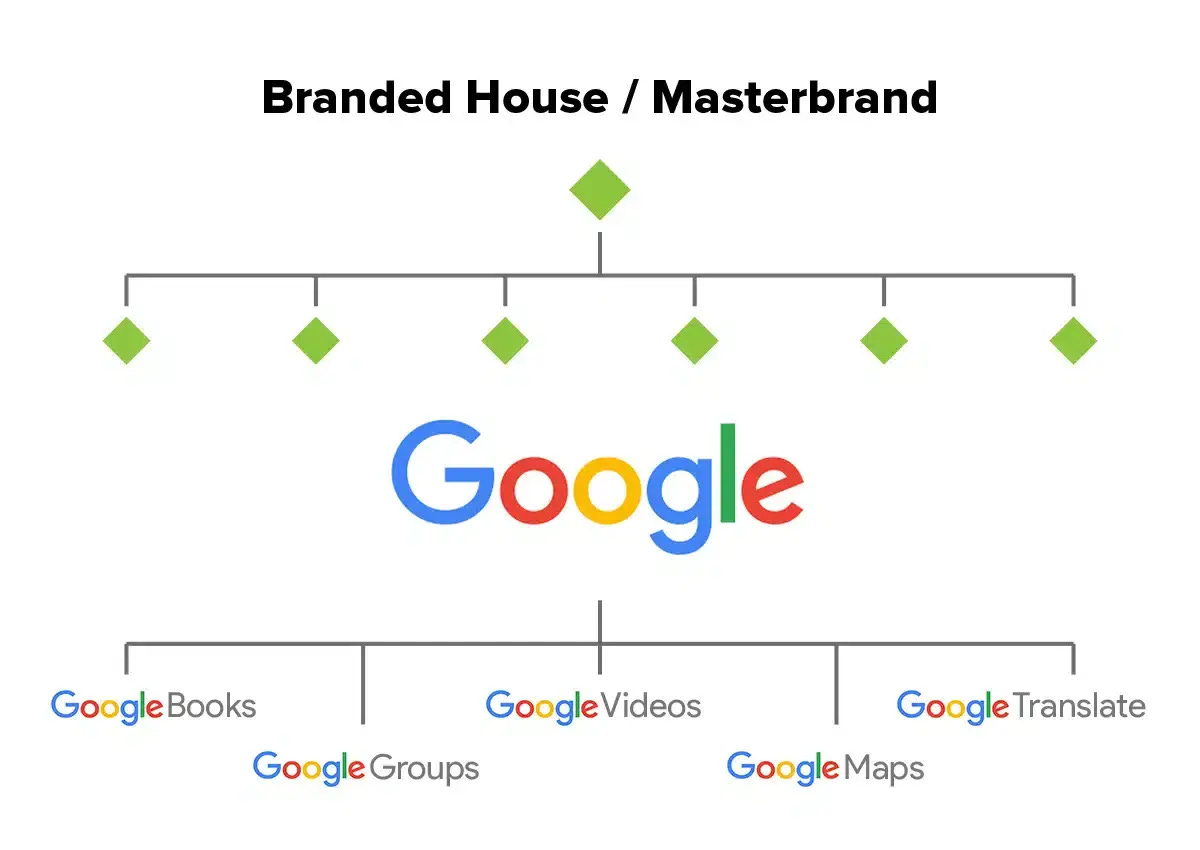

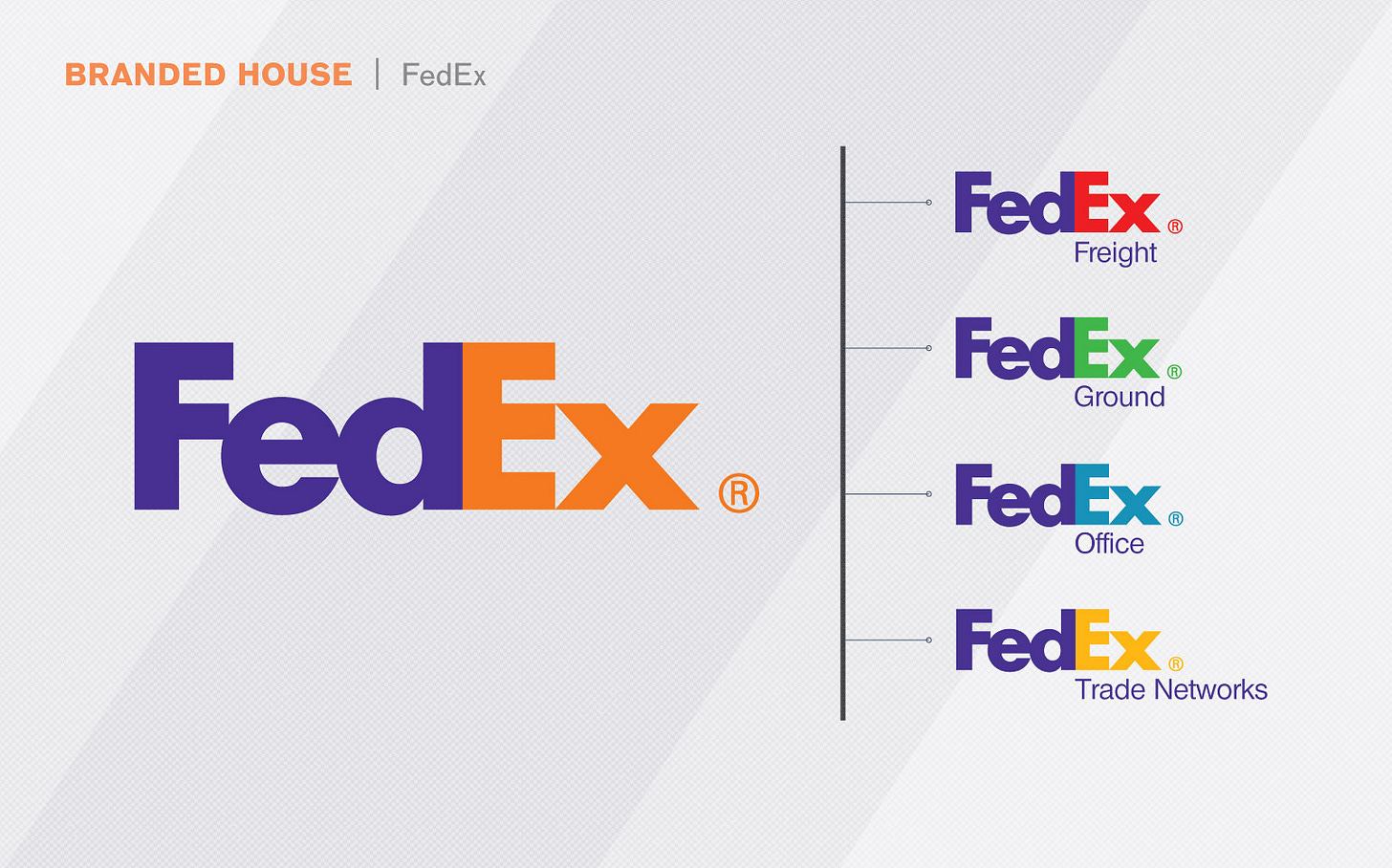

A Branded House features a single overarching brand comprising all products or services under its umbrella. This approach thus emphasizes a cohesive brand identity, within which all sub-brands are closely tied to the parent.

This means all offerings typically carry the parent’s name, allowing for consistent messaging across products. Google is a good example, along with FedEx.

A Branded House approach builds strong brand equity, as new products leverage the established reputation of the parent, triggering immediate consumer recognition and trust. There is also tremendous efficiency in marketing this way, because it keeps things simple and systematic.

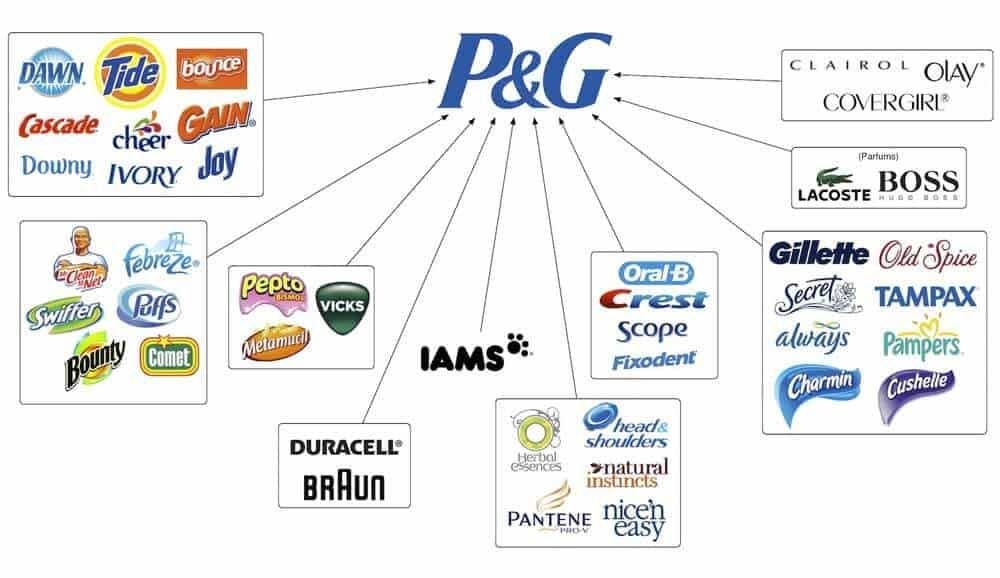

The House of Brands approach involves multiple distinct brands, each with its own identity, target audience, and marketing strategy. This allows for greater flexibility and specialization and autonomy. Good example is Proctor & Gamble, which comprises all sorts of independently recognized brands.

Because each brand operates on its own (there aren’t, for example, P&G commercials), they can tailor marketing strategies and thus appeal to specific demographics.

The is the opposite of the all-eggs-in-one-basket approach of a Branded House. Here, if one brand faces a crisis (e.g., massive recall for tainted product), it typically does not affect the reputation of its fellow brands within the portfolio.

When it comes to choosing between the two, it comes down to two big considerations:

Which appeals more to your target audience? Diversity or uniformity?

Does your firm have the resources and capabilities to manage many brands? Or is it more suited toward pushing just one?

Here, a general rule of thumb applies:

Companies own products, but consumers (and employees) own the brand.

Brands go beyond mere legal ownership of image and name. They’re really built on the shared experiences and perceptions and identities cultivated across both consumers and employees. I can be a “Mac guy” but it’s almost impossible to be a “P&G guy.”

Apple operates as a Branded House, where all its products are closely tied to the Apple brand. The consistent use of the Apple, Mac, and “i-whatever” names, replete with the Apple logo, work to reinforce a unified brand identity across its offerings. It is a lifestyle comprising an implied ethos captured in synergistic products and services

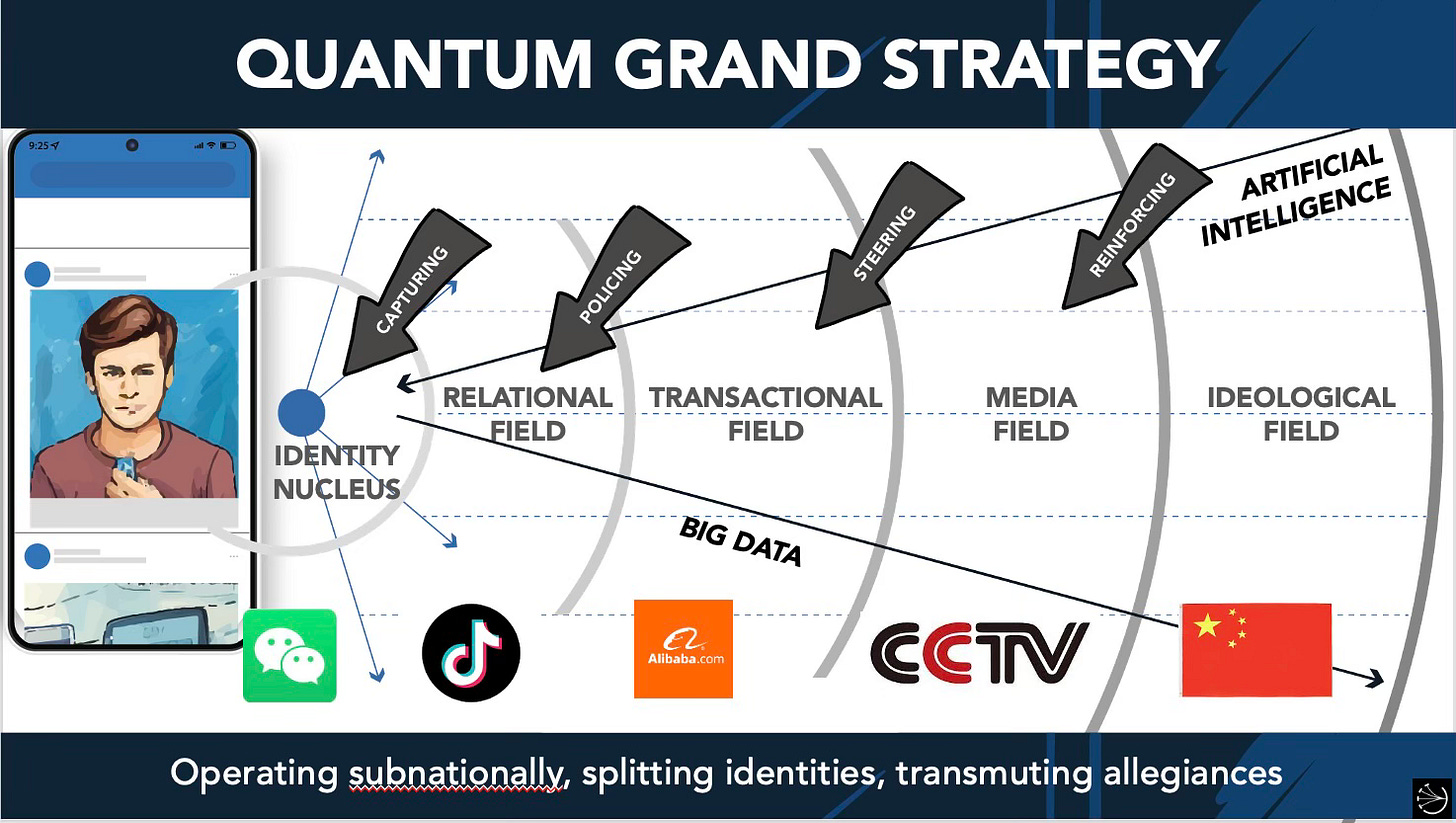

Stay with me here: not just because I’m on thin ice, knowledge-wise, but because I’m realizing — just now — that this argument immediately favors China versus the US in any competition to win the hearts & minds (or first, just stomachs & wallets) of the Global South. Because, while the US House of Brands offers the better “end” of infinite diversity in infinite combinations (yes, I am borrowing from Star Trek again), the Branded House is the better “means” of capture (the more you “buy” individual China Branded House products, the better they synergistically work together — while simultaneously giving Beijing more power over your market in all manner of ways (my Quantum Grand Strategy notion).

Recall my distinction here: in the West, the Googles and Apples and Amazons compete with one another, each seeking to become your all-encompassing Branded House. But China takes it to another level, as all its Branded Houses are compelled, by the government, to collaborate in their gains within, and captures of, foreign markets.

When you’re choosing among Google, and Apple and Amazon, you’re getting an actual choice. Far less so when you choose the Chinese variants, because all those “roads” lead to Beijing in a manner that none of our Silicon Valley giants would countenance (i.e., admit as acceptable or possible). The CCP doesn’t have to go to court to access whatever sensitive data it wants out of Chinese firms. That “duty” is a given, with zero consumer protections.

So, let’s run this string out and see if it makes sense as a mental construct.

America as a House of Brands

Our brands are our member states. There’s California Dreaming, the Sunshine State (Florida), and — my favorite (with the kidney stones to prove it) — the Dairy State (Wisconsin). Basically, you can just check out the state slogans on our vehicle license plates and you’re there, in many instances. Then think about the tourism slogans, like:

"I Love New York"

"Virginia is for Lovers"

"Pure Michigan"

"The Last Frontier" (Alaska)

"Big Sky Country" (Montana)

"Georgia on My Mind"

etc.

All of these slogans and nicknames and what-not speak to this huge variety of brands all held together by one House (United States). And yeah, there is the usual risk containment at work here: one state can take a big hit but the overall house of brands stays strong.

China as a Branded House

All of that is either harder or just plain impossible for China to emulate, because there are no valid sub-brands, as Beijing has made clear with Tibet, Xinjiang, and particularly Hong Kong. Once inside Beijing Branded House, you conform, whereas, pick any US Brand or collect them all in your blended identity (as consumer, citizen, etc.).

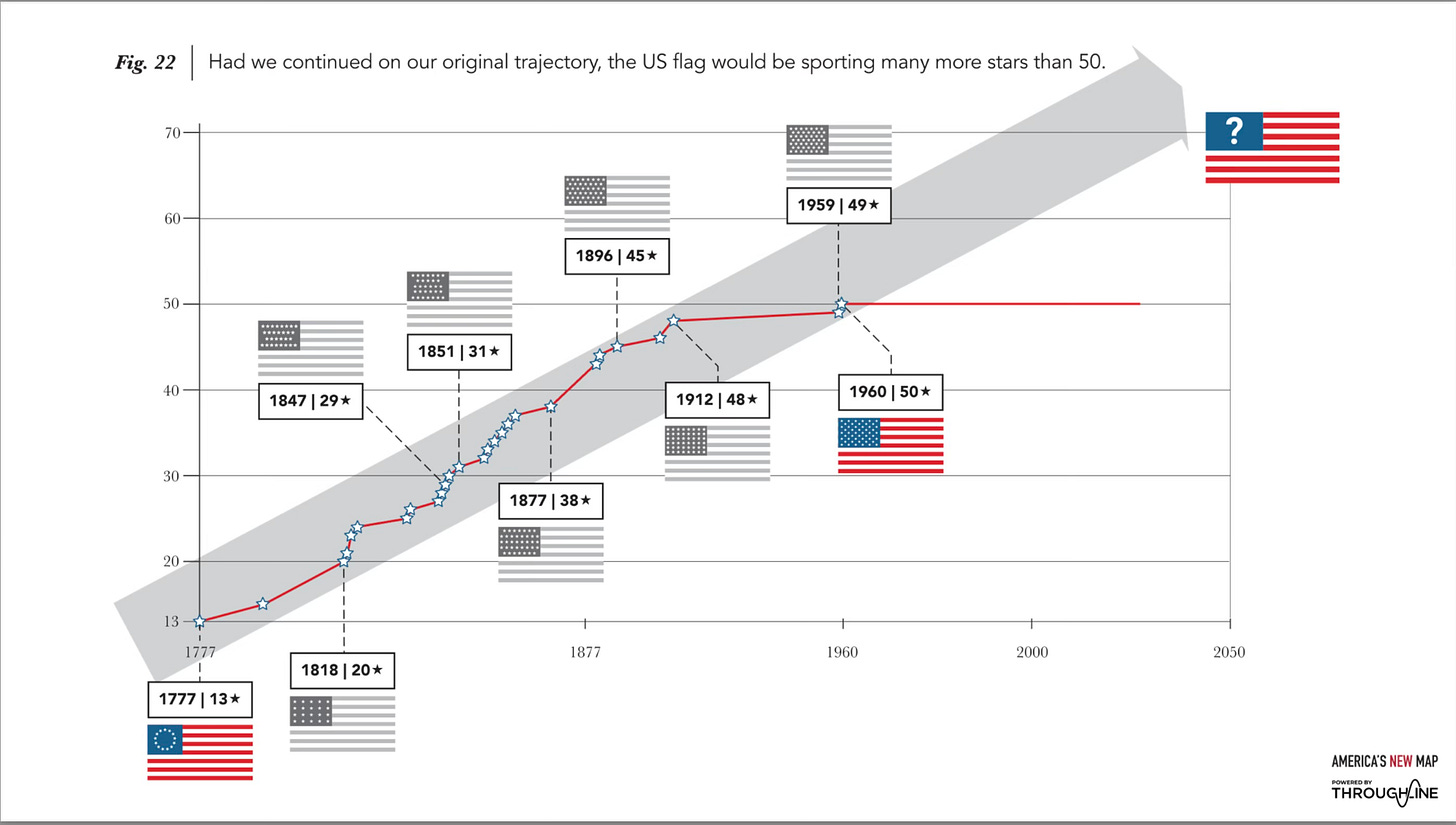

This diversity is a huge part of America’s overall brand strength on the global stage, but it’s not one we overtly promote per se — or at least very well. Because, to do so would mean opening ourselves up to accepting new brands/member-states, and right now we’re very much in the deportation/wall-building state of mind (reminding all not to confuse mere “friction” with the larger “forces” at work here).

To me, that’s the code that the EU House of Brands has cracked, and it’s an attractive one.

Yes, it’s slower and more laborious but it’s also more successful and permanent over time.

Right now across most of the Global South, China can step in quickly with its Branded House offerings (Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure package, Safe Cities security package, etc.) and it all seems very stable and integrated and backed by the strong Chinese brand of having risen, having created a middle class seemingly out of thin air, urbanizing at a stunning pace, modernizing agriculture, joining global value chains, etc.

All in all, that’s an attractive package to a struggling Global South state just looking to survive in this competitive global economy WHILE climate change incrementally devastates its landscape, depopulates its tax base, overclocks its cities and infrastructure, etc. China comes and does so much of the work itself (with its own imported Chinese labor, which typically end up staying), but it’s all on Beijing’s terms, which gives is a decided neocolonial air.

The EU’s House of Brands approach is the far harder slog alright (Meet all these standards first but then you’re in!), and for now, the EU remains a Christian-only club (it’s big limitation and a bad idea America now flirts with in the form of White Christian Nationalism). But it does show the way ahead, one that America is far better built for (Join our House of Brands as the 51st state!) … if we could get back in touch with that builder mentality that defined us so clearly for the first 17 decades of our existence as a union of states.

So, I guess I’m coming to the conclusion that China’s Branded House approach is more the “hare” route of North-South integration (quick and dirty), while the US/EU House of Brands approach is more the “tortoise” route (slow and steady).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.