Broad Framing the Digitalization of Globalization

Part of the Broad Framing Initiative series

This is the eighth and final in a series of posts exploring my preference for broadly framing any issue/news story/trend/development in our world. I am on vacation this week.

The ongoing digitalization of globalization is a profound evolution that gives lie to the notion that we are in a period of deglobalization.

As I noted in America’s New Map:

Most of us visualize globalization as this nonstop flow of container ships crisscrossing oceans. We define it as an interregional material trade unfolding in real time across real space, involving goods such as agricultural commodities, steel, cars—tangible items all. All of that is still true; it just no longer captures what expands globalization today.

Globalization now includes the Weeknd song downloaded 3.4 billion times around the planet via Spotify—the world’s largest music-streaming service. It is also a Nigerian schoolchild receiving online tutoring from Canada, a 3D printer in Brazil pulling designs from Europe, and China’s video-based social media platform TikTok serving as a psyops war zone for competing global narratives on Russia-v-Ukraine. All these online transactions involve service delivery and money changing hands—even when they are nominally “free” to users (e.g., mapping, navigation, email, videoconferencing).

The globalization of the 1990s and 2000s was a goods-intensive phenomenon, which, since the Great Recession, has flatlined. Today’s globalization, rising phoenixlike from the ashes of that worldwide financial crash, features service-intensive trade with exponentially expanding data flows. Global data flows were negligible at the turn of the century. Per the McKinsey Global Institute, they now account for more value added to global GDP than do traded goods—the effective digitalization of globalization. Remember that the next time some pundit declares globalization dead and buried.

In the decade surrounding the 2008 crash, cross-border data flows and cross-border bandwidth-in-use jumped forty-five-fold. If the previous era’s globalization leveraged cheap transportation, then this one capitalizes on cheap communications. Every global transaction today contains digital content, even as we do not yet possess good methods for measuring data flows—much less policing them.

There are three key ways I like to broad frame this development.

First, there is understanding that globalization has logically peaked in its tendency to spread out global manufacturing chains. In the 1990s and 2000s (peak globalization of materially-based value chains), the West went crazy integrating rising Asia into its supply chains so as to take advantage of the sequential Japan—>Tigers—>China—>SE Asia demographic dividends, now shifting to South Asia and India in particular.

In effect, that rapid and profound expansion of global value chains (how stuff gets put together in products) stretched as far as it could go and really can’t today stretch any farther and still make economic sense (eventually, the logic and cost-savings of proximity kick in, resulting in today’s “near-shoring” movement).

Understand, that shift to near-shoring would and did logically unfold for purely economic reasons, meaning whether or not America assumed a Cold War containment strategy vis-a-vis China.

Now, with East Asia largely “risen” and increasingly consuming most of what it produces, we’re seeing the region approach the level of trade integration (50%) that marks the super-integrated EU (more like 70%).

Understand here: the EU counts all its cross-member trade as “trade,” when America does no such thing regarding our 50 member states. If we did, our numbers would be off the charts.

But it is true that our trade integration with both North America (40%) and Latin America (teens) is lagging, logically providing even more economic rational for intra-hemispheric trade and investment integration …. EVEN BEFORE we calculate our fears of China moving into our hemisphere AND/OR thinking about how we should pursue such integration as a proactive strategy of limiting climate change’s devastation across our hemisphere’s lower latitudes.

So, that’s one way to broad framing these larger structural changes that allow digital traffic to become more prominent in the global economy.

A second way is just to frame this development as the next logical stage in globalization’s evolution from being manufacturing-centric to being service-centric, meaning that the same competitive pressures once before unleashed on manufacturing sectors are now coming for various (but not all) service sectors. In short, globalization’s impact is expanding from its previous focus on blue-collar workers and now includes white-collar workers and industries.

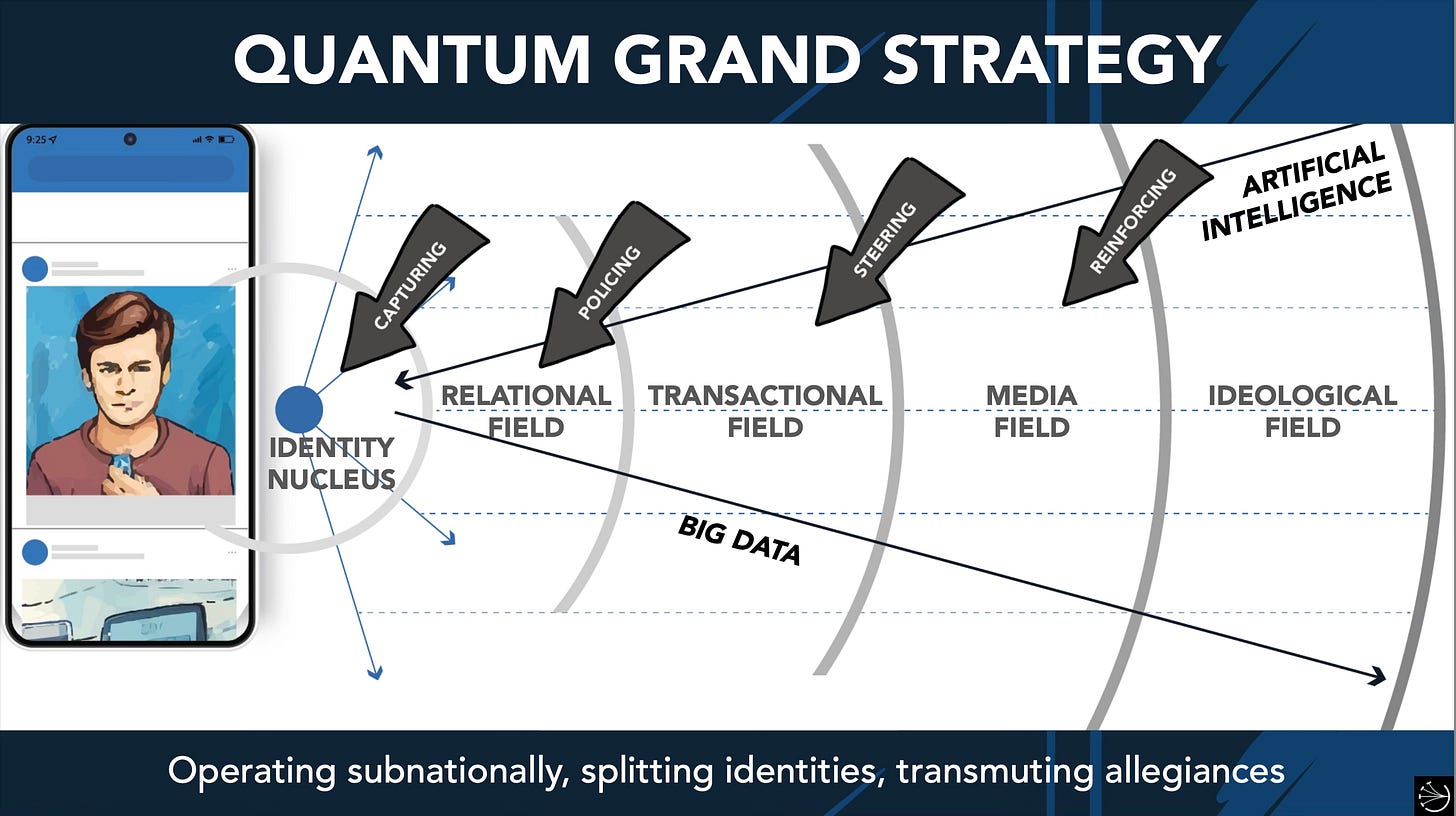

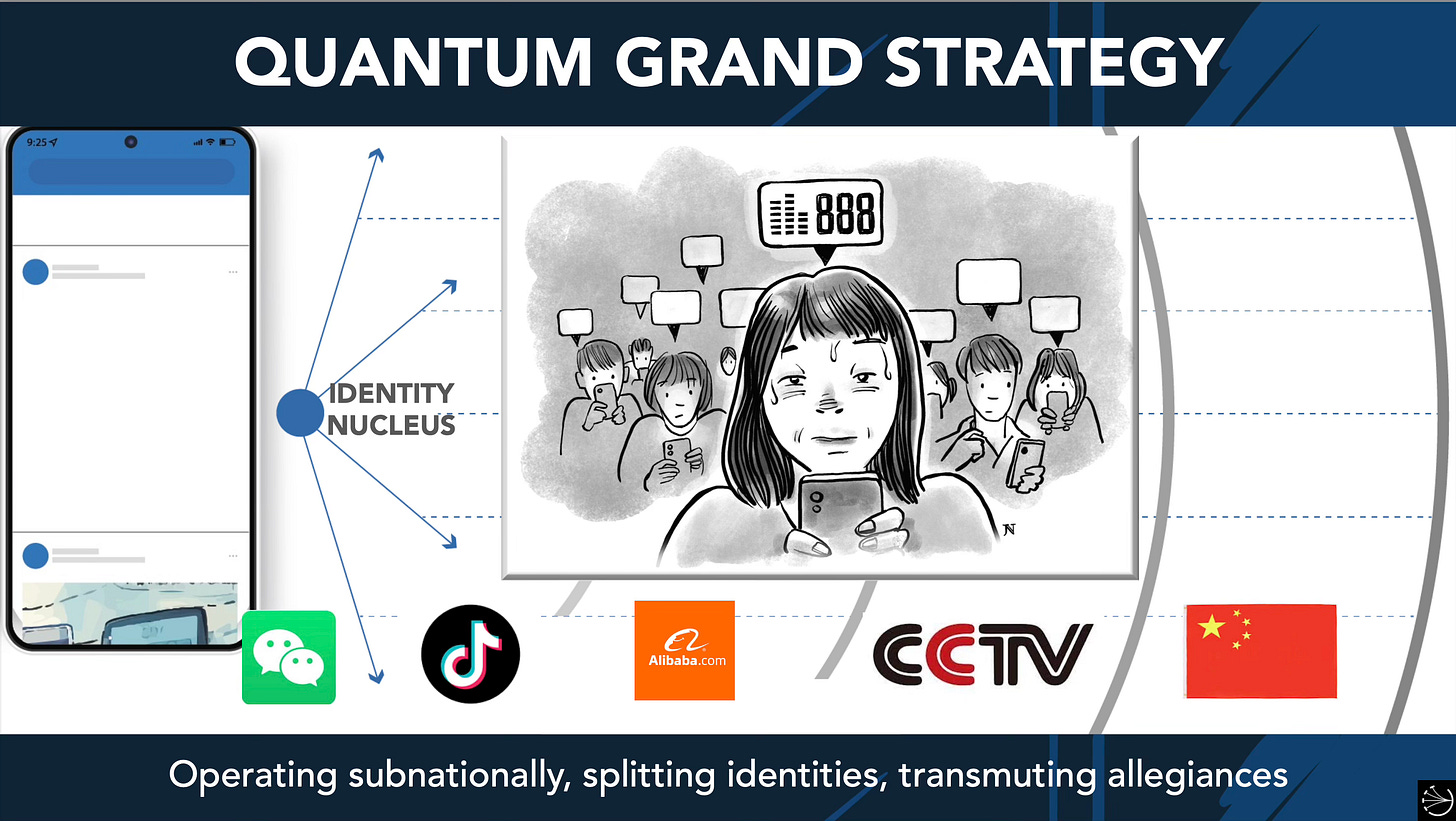

A third way to broad frame this digitalization wave is to recognize it as the primary venue for a superpower brand competition aiming to capture the hearts and minds of that emergent global majority middle class who can now be quite directly and individually targeted for a sort of ideological capture — namely, my notion of China’s (and Russia’s) Quantum Grand Strategy of sub-nationally penetrating and capturing individuals within targeted states.

Thus, when you add it all up, you come to the following, broadly-framed conclusions:

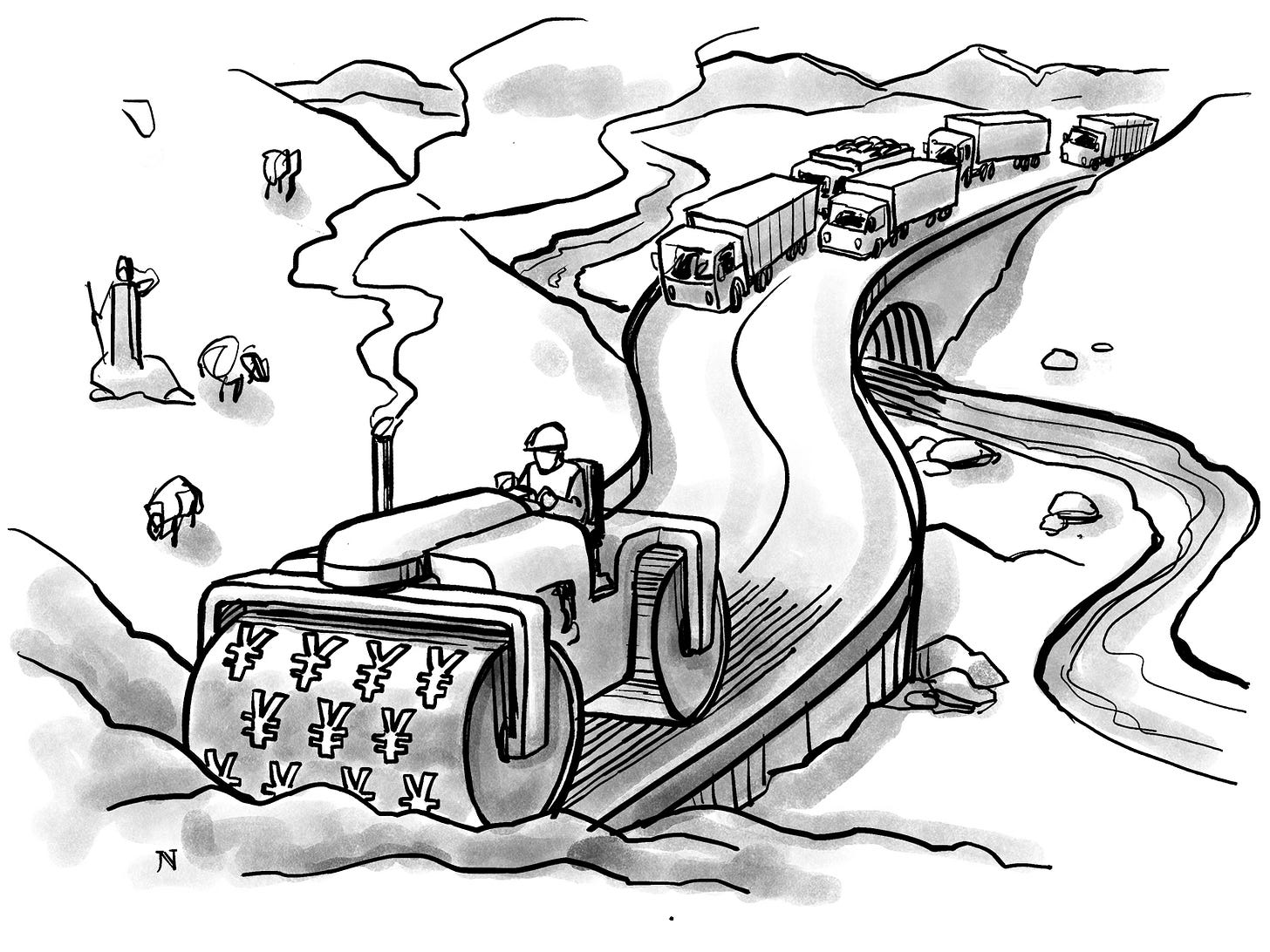

We are in a period of regional consolidation of globalization’s previously rapid expansion around the planet — one that rewards first-mover actions by superpowers looking to lock-in their network centrality in various regions around the world (see China and its BRI + Safe/Smart City solutions).

Globalization’s peak-period (1990s-2000s) of extending material supply chains is being superseded by a new wave of network building to accommodate and extend globalization’s follow-on period of digitalization.

That cyber realm will constitute the primary venue for superpower competition to ideologically capture that global majority middle class. China offers a model of economic and surveillance infrastructure integration. Europe offers a model of economic and political infrastructure integration. Meanwhile, America uncomfortably resembles Russia’s old Cold War offering of military integration, meaning we are not truly “in this game” for now (except on the level of sanctions).

America’s currently narrow offering (more stick than carrot) reflects our inability to broad frame the global developments and trends identified in this series, which is why Throughline Inc. and I are pursuing this Broad Framing Initiative. We want America to see the world for what it truly is and not reflexively impose Cold War paradigms and thinking for the sole reason of their familiarity among our geriatric leadership.