The dream is always the same: America will successfully enlist India to box in China’s efforts to rule global value chains while moving up the global production ladder to higher-end goods.

That’s a mouthful, so let me unpack because sometimes I fall in love with my own phraseology.

A global value chain (GVC) is an interconnected series of stages involved in producing a product or service that is ultimately sold to consumers. Each stage in the GVC adds value, and at least two of these stages occur in different countries, allowing firms to capitalize on differences in labor, resources, and capabilities.

The best way to enter a GVC is by using the attraction of cheap labor to pull in foreign direct investment to either buy up existing factories or build new ones within your country. Then you’re in the mix.

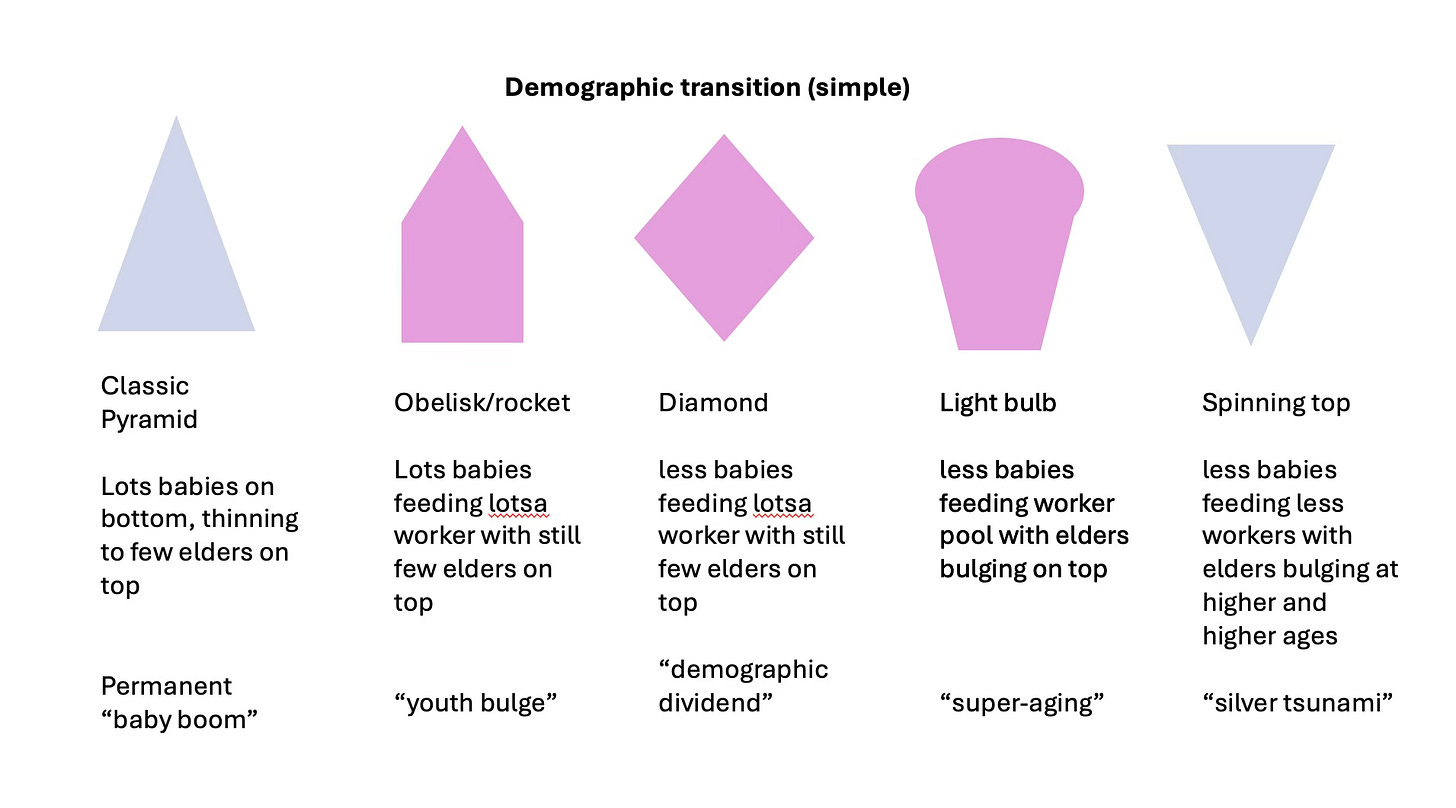

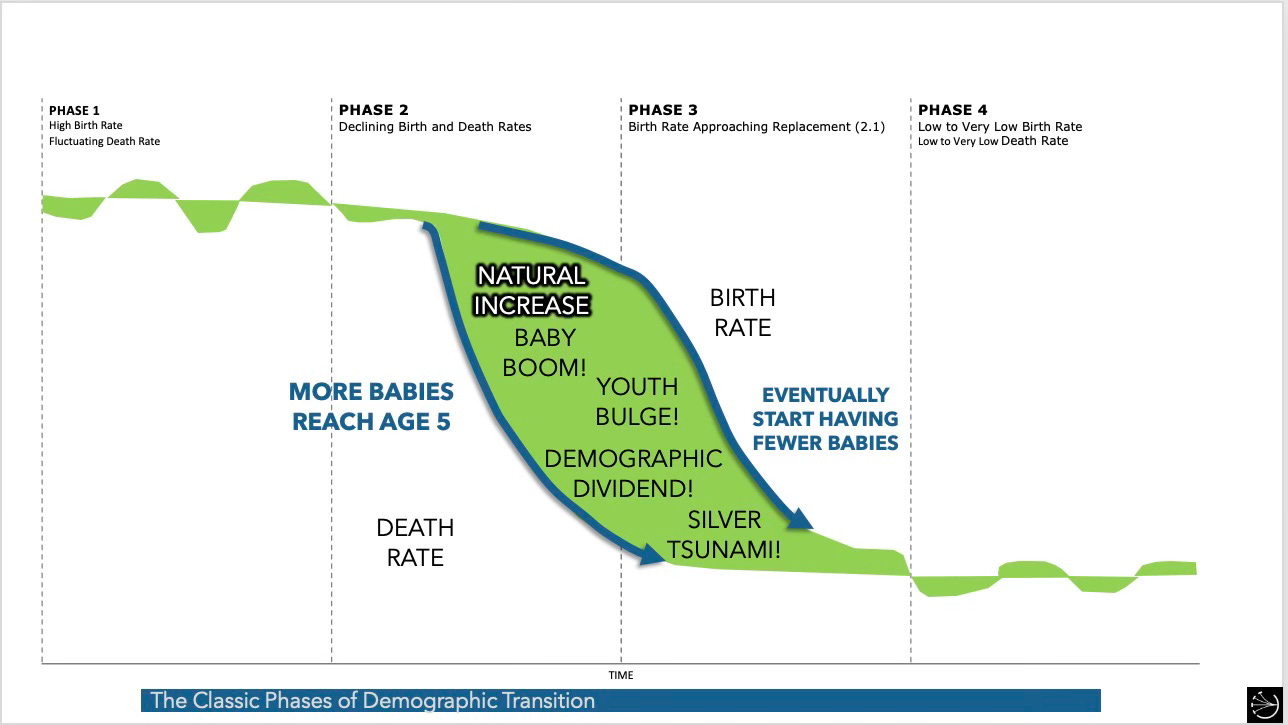

A demographic dividend refers to the stage in a demographic transition when your age pyramid assumes that diamond-like shape where you are plump in the middle working ages and thinner both above (elders) and below (kids).

China’s demo-div ran through the 1990s and 2000s. It’s now over, as China stockpiles elders and faces a shrinking flow of youth from here on out. But China attracted boatloads of FDI and got itself integrated into all manner of GVCs.

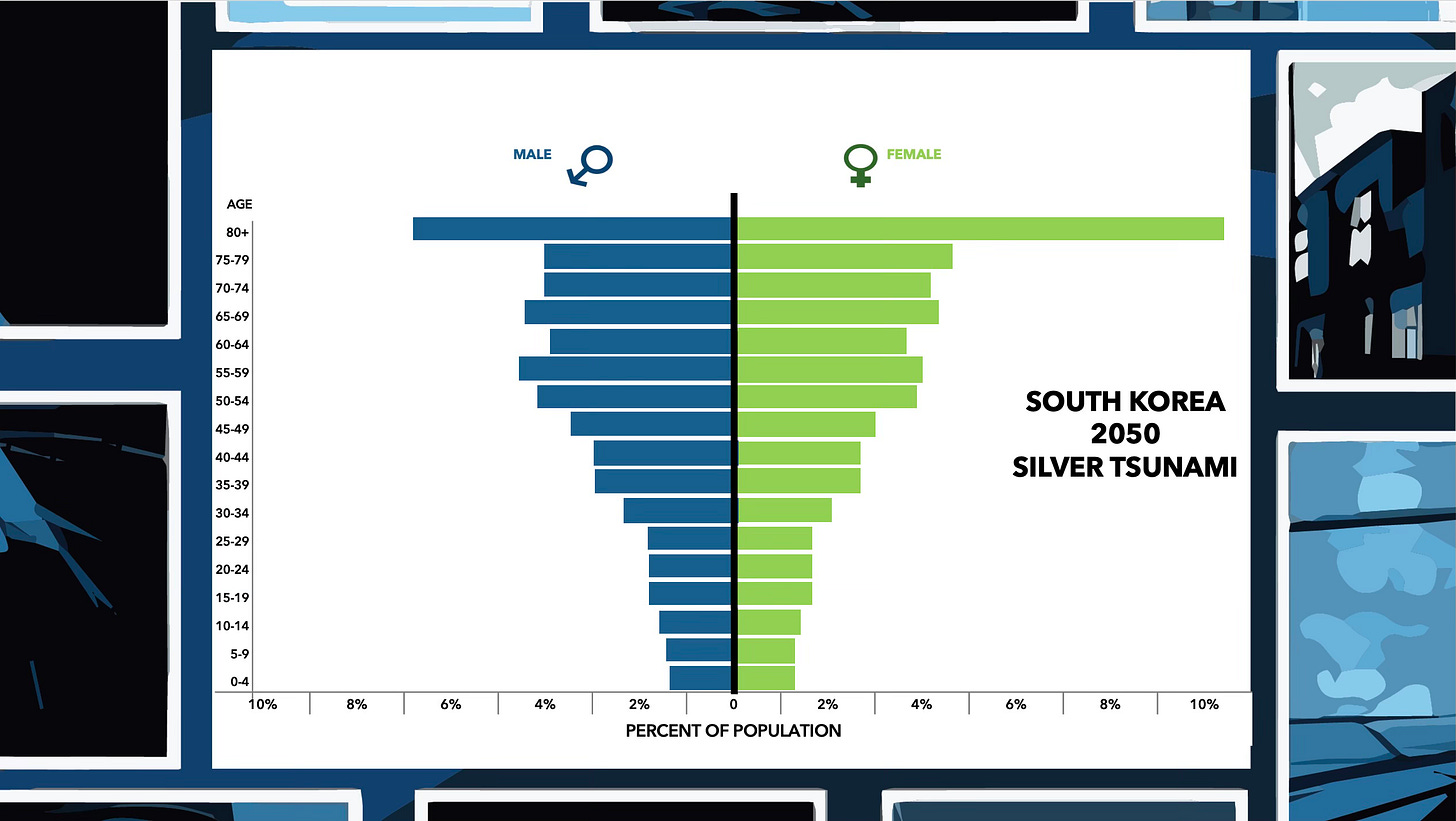

Now, as China starts aging and that diamond shape turns into a light bulb shape with a bulging elder population. Eventually, China heads into silver tsunami territory where the old outnumber the young at basically every point in an inverted pyramid, or what I dub the “spinning top” shape that nations like Japan, Korea, Greece, and Italy will reach before anyone else.

To remind from my briefing slides:

Okay, so that’s the demographic transition that gets typically triggered when you, say, modernize your agriculture (mechanize it), driving farmers off the land and into the cities where they inevitably shift from a rural procreation rate (lotsa babies = farmhands) to the urban one (fewer mouths to feed). There is that time lag (learning curve) between the two rates and that is where the abnormally large generation is created that then moves up the pyramid.

So, back to my story:

China’s had it moment, demographically speaking, but India is all teed up and ready to roll on its demographic dividend (rocket shape morphing into diamond). That unusually large Indian cohort numbers in the half-billion range, so a HUGE dividend.

Trick for India: 45% of its labor still sits in rural areas/agriculture, so we’re talking big internal migration amidst climate change’s crescendoing impact on Indian agriculture (going to be bad).

India right now has trouble finding work for all its youth, who enter the workforce to the tune of about one million souls EVERY MONTH!

So, yeah, India is super-incentivized right now, if its going to solve that youth bulge situation, to integrate itself in every possible GVC out there.

So, that’s where things stand with our two Asian behemoths:

China is post-dividend and now super aging, and it STILL has a vast youth unemployment problem, which is why Xi is still pushing export-driven growth like there’s no tomorrow because her refused to unleash domestic consumption for ideological reasons.

Problem is, as India’s demographic dividend kicks in, it starts attracting the FDI that used to go to China (and which the West now discourages due to the rising perception of threat), because it’s clearly the up-and-coming center of cheap labor in the system — for now (understand that the Middle East and Africa are poised to enjoy a combined demographic dividend roughly twice the size of India’s later this mid-century).

So, it’s like various trains leaving the station: once the demographic transition begins, there’s no turning back. You have to join those GVCs as much as possible, being as unpicky as possible.

And that’s where America’s desires to enlist India in boxing in or containing China comes into play, the problem being that our thinking on this subject seems to ignore the larger demographic and global economic realities involved.

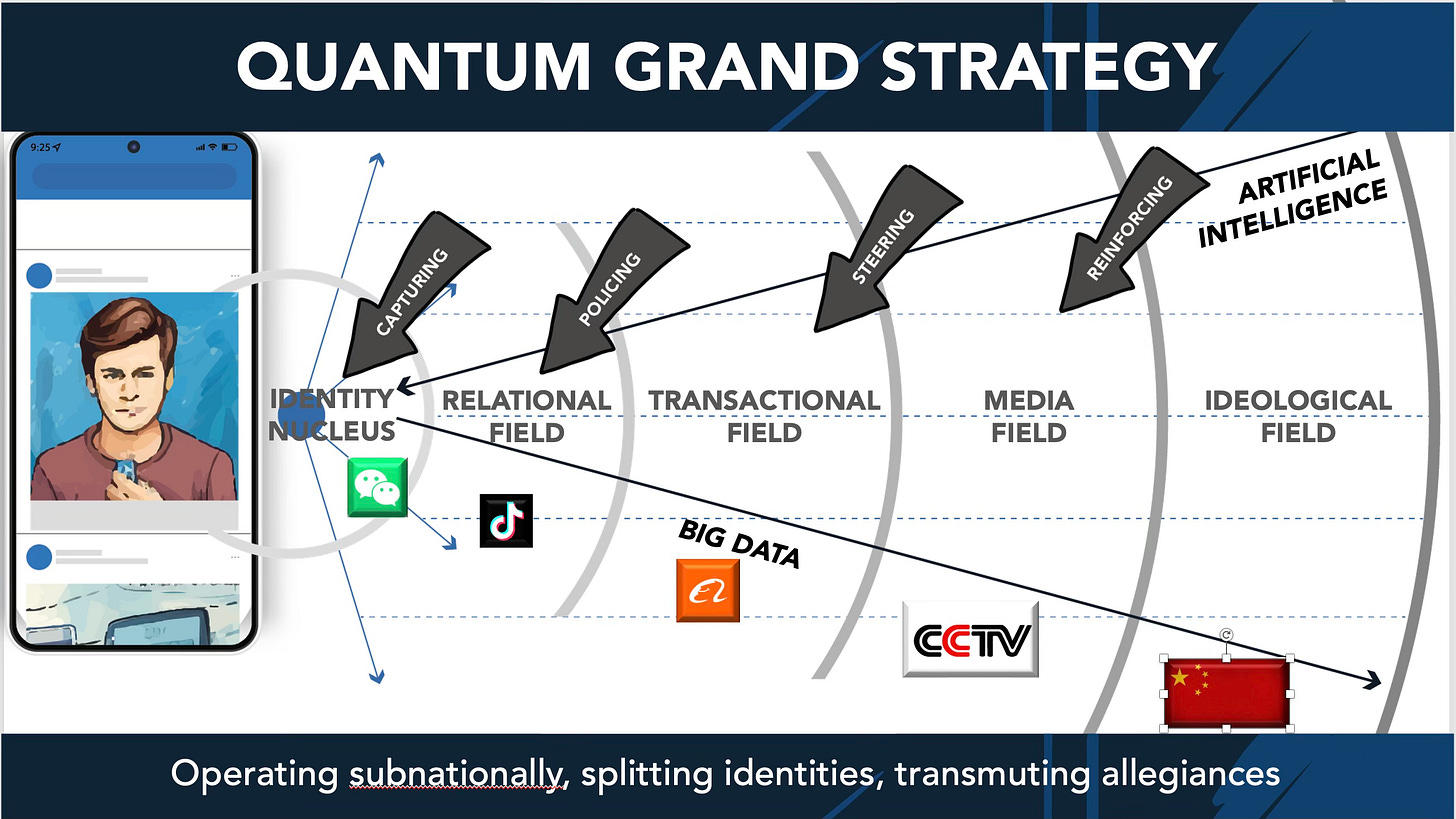

Again, China has little choice now but to move up the production chain from cheaper, less tech, mere assembly of goods to later segments of GVCs in which the high-end stuff is put together. So, whereas China was happy enough producing cheap consumer goods back in the demo-div day, now it feels compelled to move up the ladder to the higher-end stuff, which fits their ambitions to dominate global markets in the great move from 5G networks to the Internet of Things (IoT) to the AI of Things (AIoT), or what I call China’s quantum grand strategy:

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, India has little choice (for now) but to plug into any GVC it can find at any level to get integrated in them as much as possible while its demographic dividend plays out.

Does India particularly want to insert itself at lower levels of the production ladder (or earlier segments of a GVC), looking up at China seeking higher ground, so to speak?

No, India does not.

But India is super incentivized to not care about that for now.

So here’s the problem for the US: We seek to de-risk our own economy from China’s deep penetration of the world’s GVCs, and we’d like India to do the same by, in effect, eschewing any such interdependency.

But that’s entirely unrealistic on both scores. There’s just no way to extricate the US economy from all those GVCs, and the more we try, the more China will simply migrate, quite naturally with us, to those rising segments of GVCs that present themselves as being in their demo-dividend phase.

Right now that’s SE Asia. China has been sending FDI there for a while, moving factories in the process, and slotting in those workforces in its GVCs as it moves up to higher-end production levels.

[Mexico is another route: China Conquers Mexico’s Automotive Market, and the US Is Worried. It’s the same workaround logic, just applied closer-in to the US market.]

America thinks we’re decoupling from China because we’re importing more from SE Asian nations, but those nations are still integrated with China in GVCs that are simply growing longer by their insertion.

Over time, India’s attractiveness as a huge and long source of cheap labor will pull that FDI flow from SE Asia (already happening, really) and India will be the next-up to be integrated into these same GVCs.

Thus, America’s dream of de-coupling from China and preventing India from coupling with China in these GVCs is a fool’s errand. The economic logic and the demographic reality undergirding that economic logic are just too strong.

So, here’s the piece that triggered my post:

India’s growing reliance on China poses challenge for U.S. trade strategy

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.