Owning a home used to strike most Americans as the safest and easiest way to accrue wealth simply by paying down the mortgage and “banking”

the rising value. That is why so many of my generation were raised to believe you’ll do anything BEFORE not paying your mortgage.

I learned the hard way during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and the subsequent Great Recession that that is the wrong way to think. Having built a home in Indiana in 2006, I did everything I could to keep up the mortgage payments even as my income dropped precipitously and stayed down for a scary long stretch. The entire world was telling me that, suddenly, my work was worth about half as much — no matter where I turned, and yet, the bank wanted the mortgage paid no matter that the home’s value had similarly been cut in half. It was like everyone was scrambling to save things but the banks didn’t get the memo.

So, I took the plunge: I stopped paying the mortgage and put the house up for a short sale. Man, the bank (Wells Fargo) did not like that. All manner of threats ensued right up to the sale that netted half my mortgage because that was how the world was pricing everything right then — except for Wells Fargo with my mortgage. We beat the bank seizure by about two days, as, in the end, Wells Fargo took their money and wrote off the rest.

The “great punishment” of bad credit for several years didn’t really matter, as we were in no mood to buy again for a good long stretch after that experience and, meanwhile, home renting got very cheap and easy.

Thus my lesson in life (one I probably would have learned much faster if my Dad was still around and advising me) was: treat your family finances like a business and when a major asset like your home is screwed by the market, dump it as fast as you can and never look back.

Still, it was a tough lesson to learn. Forces beyond your control suddenly change the value of everything — including you. But your mortgage company? Couldn’t care less.

Home ownership is much on my mind right now, as my spouse and I plot our return to Wisconsin next year. Why? Nothing really keeps us in Ohio (old job brought me here) and, as we contemplate the next phase in our lives, we’d greatly prefer being back home — no matter how things go down (What will civil war look like in Green Bay, one wonders). Plus, quite frankly, both my spouse and I are almost genetically predetermined to want to live in Wisconsin, where the allergies are far more tolerable for us than just about anywhere else, proving, I guess, that — as my Dad liked to say — You can take the boy out of Wisconsin but you can’t take the Wisconsin out of the boy.

We currently own a house in Ohio: a funky-as-hell midcentury modern in a small subdivision of midcentury moderns in Yellow Spring OH, considered a supremely desirable home market. Previous owners never even put the house up. Neighbor found out their plans and that news got to me circuitously, pushing me to immediately drive from Madison through the night and a wicked snow storm to south-central Ohio. We met the owners that morning, were blown away by the house (feels very Frank Lloyd Wright), and couldn’t believe the asking price. Handshake right then and there sealed the deal.

We have loved this house, and if I could move it to Wisconsin I would, but it’s not enough to keep us here. To me, it’s just a piggy bank to be cashed and cash it we will.

But now we face the question so many other Americans face today and going forward: Where do we want to live amidst climate change? We can’t just buy a house anywhere only to be told X years down the line that, whoa buddy! Your place just became uninsurable.

Fortunately, for us, my Mecca is Green Bay, where my Mom was born and grew up amidst the Packers early years as her dad served as the team’s fixer and general counsel (right through the famous story of his threatening Curly Lambeau with an investigation into his spending habits when Curly tried to whisk the team away to Los Angeles — thus scaring him off to coach the Redskins in Washington instead and keeping the Packers in Green Bay [hence, Jerry Clifford’s inclusion in the Packer Hall of Fame]). I was born just south of Green Bay on the northern shore of Lake Winnebago in the town of Chilton, before my family moved to the southwest of the state (Boscobel), where I grew up.

But, to me, Green Bay has always remained my cosmic center of gravity. Growing up during the Packer’s worst decades (1970s and 1980s), I oft felt like some NFL version of Princess Anastasia separated cruelly from my birthright and home! Nobody knew I was really Packer royalty by birth!

Eventually, that painful nightmare was ended when I got two season tickets in 2001 and my wider family eventually got another 8 so that we now have three family reunions tailgating at Lambeau each year (we possess the old Milwaukee ticket package of two regular season games [and one preseason] now known as the Gold tickets). My birthright restored, I now dream of a retirement (way down the road) that sees me working the stands as one of the yellow-vested crabby old men who police the drunks on behalf of the stadium!

A fellow can dream, can he not?

Anyway, I’ll be completely honest here: if Green Bay wasn’t considered good in terms of future climate change, I wouldn’t think of buying there. Used to be we worried only about schools, but now, particularly at our stage in life, my spouse and I are thinking more along the lines of what makes the most sense, climate-wise?

The fact that so many of these sites (with their calculators and indexes) exist is a huge sign: risk management elements in the economy and government are planning ahead. The real question is, will you get the memo?

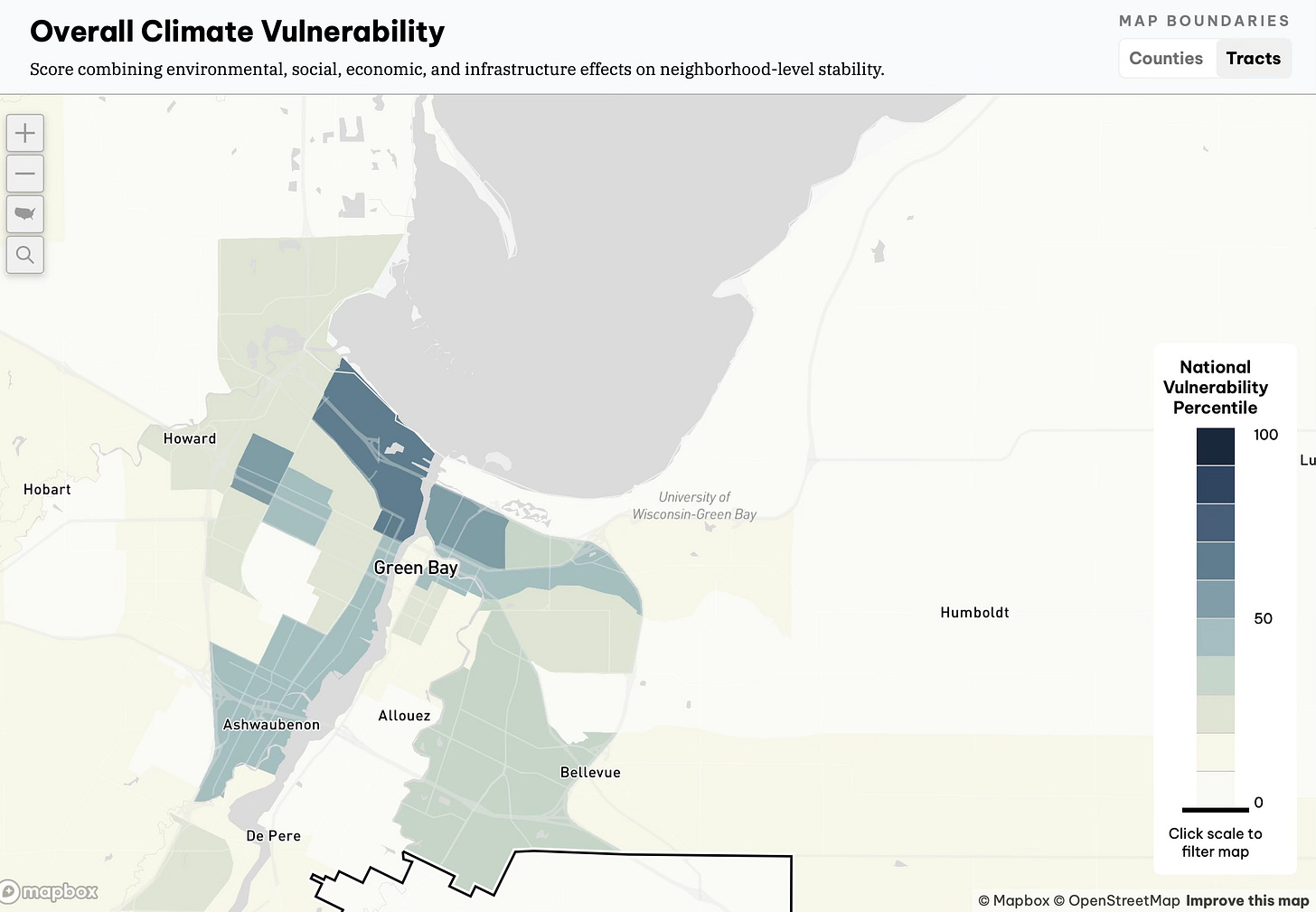

Brown County, home to Green Bay and its various suburbs (we’ll probably pick one eventually after renting a year or two), is a pretty safe bet for everything except inland flooding (duh!).

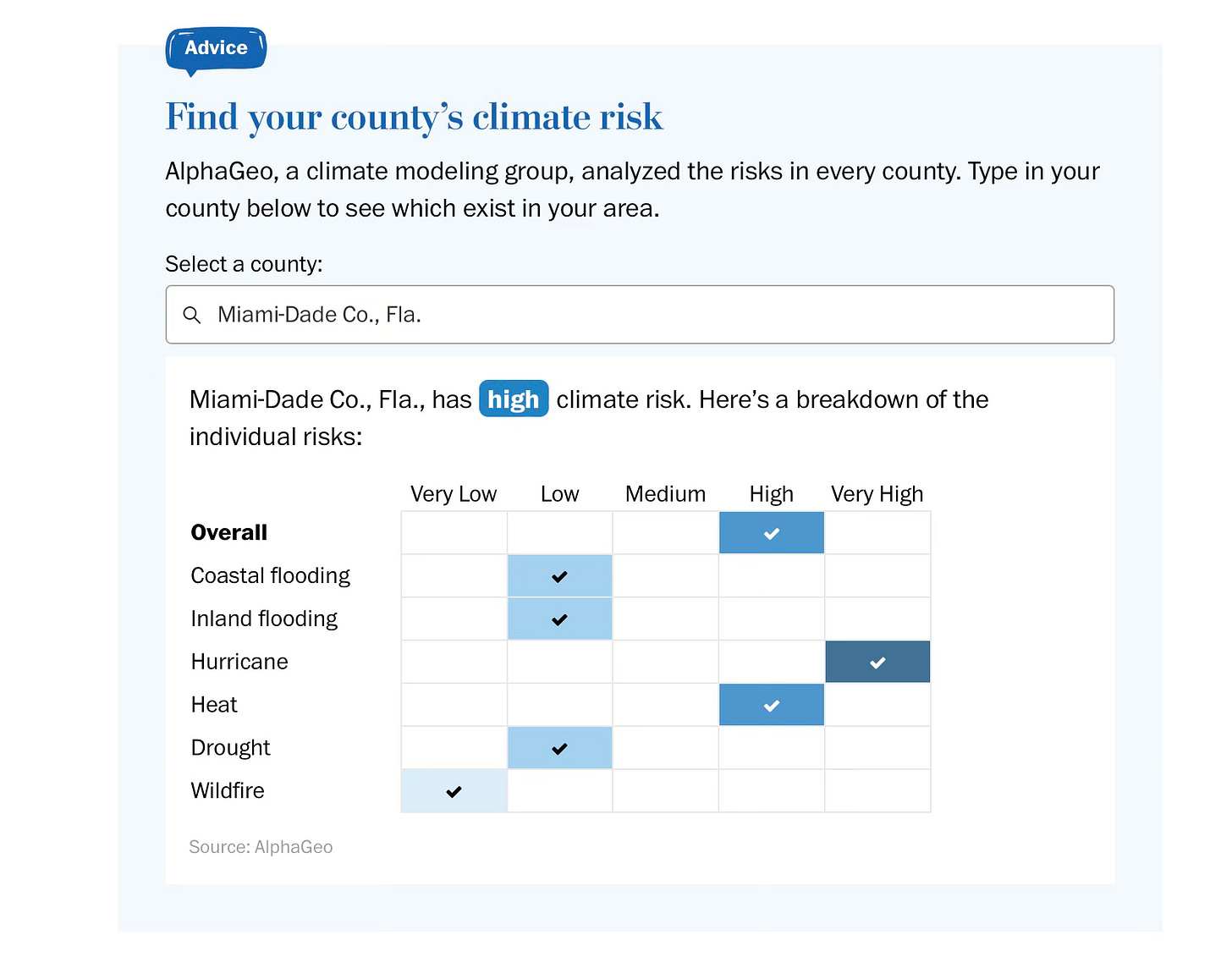

But take a look at a place like Miami:

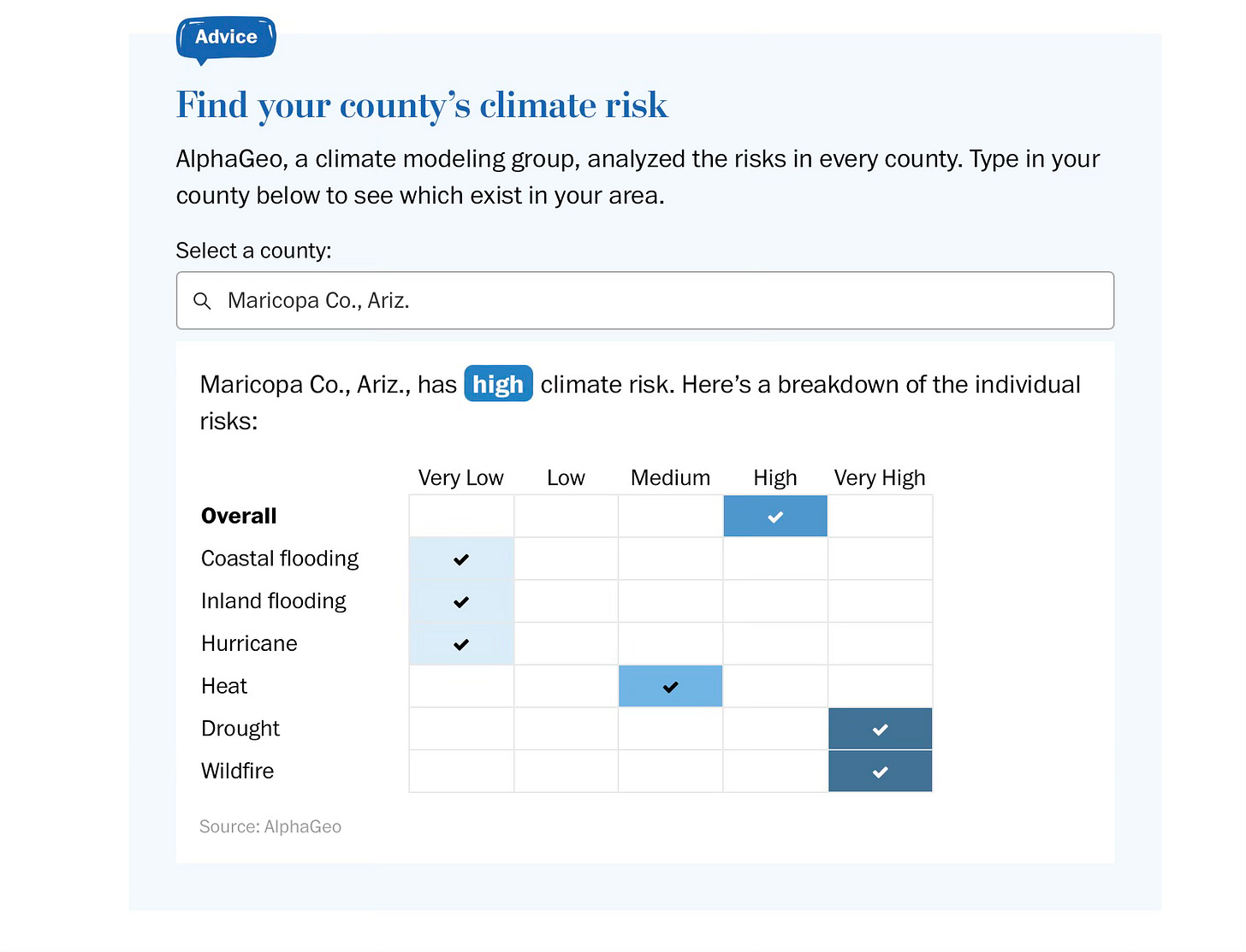

Or Phoenix AZ:

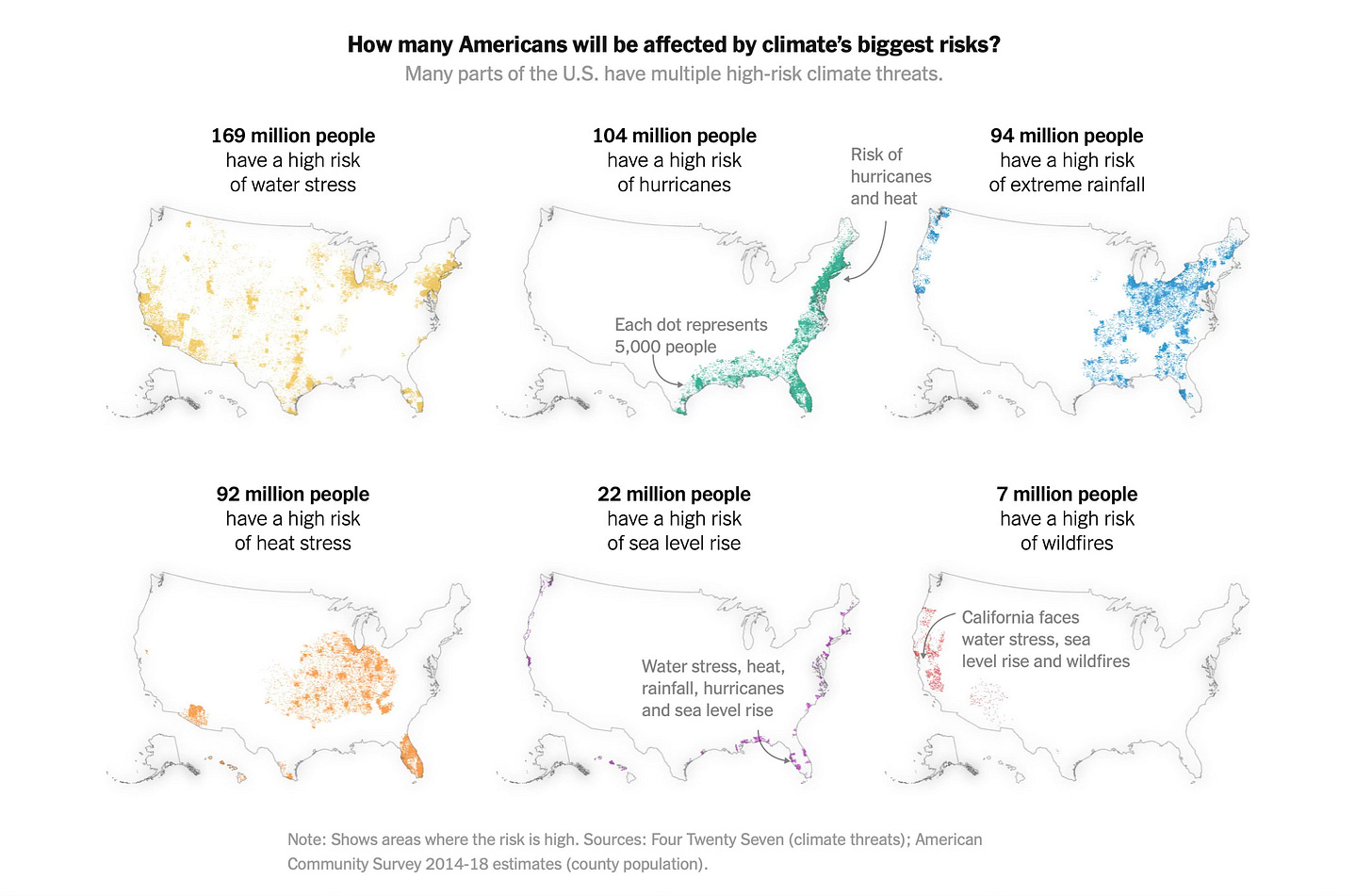

And yeah, you get this feeling that there’s not really any place in America that won’t be impacted — many on some very profound levels.

So, here’s where the insurance “rubber” meets the climate “road”:

Nearly all American homeowners are covered by some sort of insurance, but research from CoreLogic suggests that 64 percent of policies fail to adequately account for disaster risks. In high-risk areas, this gap is often worse: 80 percent of homes in California’s wildfire regions are underinsured, and 90 percent of California homeowners do not even have earthquake insurance. Nationwide, over 40 percent of the $145 billion in losses due to natural disasters in 2021 was not covered by insurance. These gaps can cause financial ruin for homeowners when disaster strikes, leaving them responsible for tens of thousands of dollars in repairs. And, as many cannot rebuild, this leads to slowed recovery in the region and causes many underinsured homeowners to ultimately default on their mortgages.

And, per today’s WAPO story:

In 2017, Angela and Donald Brudos moved to a modest, ranch-style house where the Caloosahatchee River empties into the vast calm of the Gulf of Mexico. Despite Florida’s reputation for extreme weather, it held out the promise of an affordable paradise where they could retire.

“We felt safe,” said Angela, “because neighbors told us it had never flooded.”

But even as the Brudoses’ home remained perfectly dry, climate change was beginning to reshape the housing market here — and in vulnerable places throughout America. By the time they settled in their new home, research suggests, flood risks were already making people less willing to pay top dollar for houses in waterfront neighborhoods such as theirs, eroding prices even as values marched upward in lower-risk neighborhoods.

As buyers and sellers wake up to risks on a hotter planet, Cape Coral might be a preview of what millions of homeowners throughout the country could face: a slow and almost imperceptible re-pricing of many people’s biggest asset.For the Brudoses, the risk became apparent only when Hurricane Ian crashed ashore in 2022, leaving their living room buried under mud and debris …

Nearly two years after the storm, they were still living in a trailer in their driveway. Escalating expenses and insurance delays had left them drowning in debt. To qualify for flood zone insurance, they took out a $210,000 loan to elevate their home.

“The only choice we had was to go severely in debt and raise the house, and hope by being elevated, you can recoup the money,” Donald Brudos said. “We’re scared to death.”

I have no illusions. If Vonne and I make the wrong choice on this, we could face something very similar in our retirement.

That is climate change coming home, and it is profound.

From the WAPO story:

Other Americans are facing similar challenges. Extreme thunderstormsin Iowa. Wildfires in California. Rain bombs in Vermont. Driven by painful insurance premiums and extreme weather damage, the true cost of risky properties is becoming clear. A small but growing number of home buyers are fleeing for metaphorical high ground, while others are being left behind.

I’ve seen my share of rain “bombs” here in south-central Ohio over the past three years. They are frighteningly impressive.

As one insurance expert is quoted in the piece: when it comes to risks to your family’s biggest asset, climate change is “the most important and least examined.”

Scary thought.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.