Connectivity versus content

Everyone wants the former, but the latter is an entirely different story

Solid WAPO story exploring the rising difficulties faced by streaming giants like Amazon and Netflix when it comes to maintaining access to India’s huge movie-watching market. In my understanding of history, this is an old story regarding rising powers.

Hollywood, for example, ran into this issue in the 1930s with regard to rising Nazi Germany, as the country was then the prized overseas market. So, for a significant stretch, our movies laid off the National Socialists (remember our deep isolationism and America First-ism of that decade) and saved more of their critical perspective on the Soviets/communists. Once Hitler invaded Poland, fascism was a fair target, along with communism … until Germany invaded Russia in 1940 and then, all of a sudden, the Russians were good … until they weren’t and the Red Scare kicked in for a solid dozen years or so.

Plenty of Hollywood careers did not survive those whipsaw-like movements.

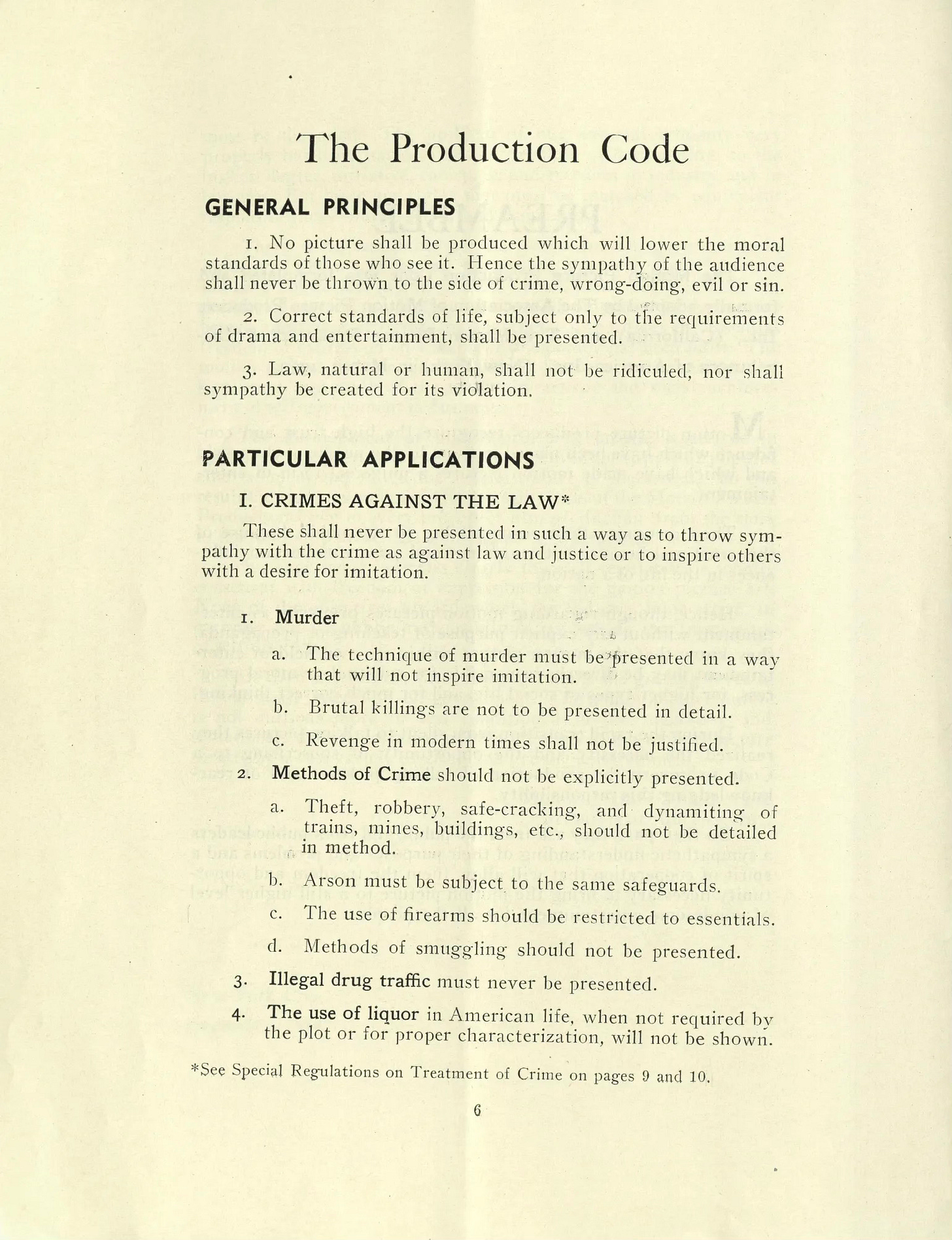

Similarly, Hollywood was long constrained by the Hays Code (1934-1968) that sought to mandate a certain morality across films, like the bad guys always either die or go to jail. The code was strongest in the early years and probably peaked with Washington’s enlistment of Hollywood in the “war effort” of the early 1940s, only to then suffer “film noir” and other assaults over the years until finally giving up the ghost, along with the dominant studio system, in the late 1960s (with the film “Easy Rider” often cited as the great turning point).

Point being, to expect “rising India” to somehow remain indifferent to its own vast movie and entertainment industry (Bollywood, based in free-wheeling Mumbai) is unrealistic, particularly as it involves outside streaming giants coming in.

This has long been a mantra of mine WRT globalization: everyone wants the connectivity, but most want controls over the content — particularly the government. So, yeah, streaming is great but watch the sex stuff, and the flouting of tradition, and the mocking of social values, and the depiction of social institutions, and so on and so on.

Bollywood has long walked a certain line on depicting Indian society, the old joke being that its musicals always feature “seven songs, three fights, and a kiss” (it may be two fights, I can’t remember). For the longest time, Bollywood musicals were very formulaic in a modernity-meets-tradition sort of way that harkens back decades in Hollywood time: modern man meets and falls in love with daughter of traditional father; traditional father rejects modern man but daughter can’t help herself, then 7 songs, three fights and one kiss later … guess who wins every time?

[NOTE in this post’s cover image how the woman is traditionally dressed, her wooing man is dressed in a modern fashion, and all this tradition hangs over both as a cultural backdrop.]

No doubt, Bollywood has produced plenty of gritty and edgy films in recent years, but now it’s bumping up against the rising India phenomenon, which naturally seeks to enforce, via the BJP government of PM Modi, a certain cultural coherence and pride that inevitably favors and celebrates the dominant Hindu culture. Think back to rising America and you will spot similarly conformist vibes and fears — even hatreds, along with serious intolerance of counter-narratives and “others” within our ranks.

From the WAPO piece:

When the U.S. streaming giants, Netflix and Amazon’s Prime Video, entered India seven years ago, they promised to shake up one of the world’s most important entertainment markets, a film-obsessed nation with more than 1 billion people and a homegrown moviemaking industry with fans worldwide …

In the last four years, however, a chill has swept through the streaming industry in India as Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party tightened its grip on the country’s political discourse and the American technology platforms that host it. Just as the BJP and its ideological allies have spread propaganda on WhatsApp to advance their Hindu-first agenda and deployed the state’s coercive muscle to squash dissent on Twitter, they have used the threat of criminal cases and coordinated mass public pressure to shape what Indian content gets produced by Netflix and Prime Video.

Some glimpses of self-awareness there: the piece admits the outsiders coming in intended to “shake up” a huge national industry and eventually triggered a “chill.” Can you imagine giant Indian or Chinese platforms coming into the US market looking to shake things up and NOT running into some sort of reaction? Tik Tok much?

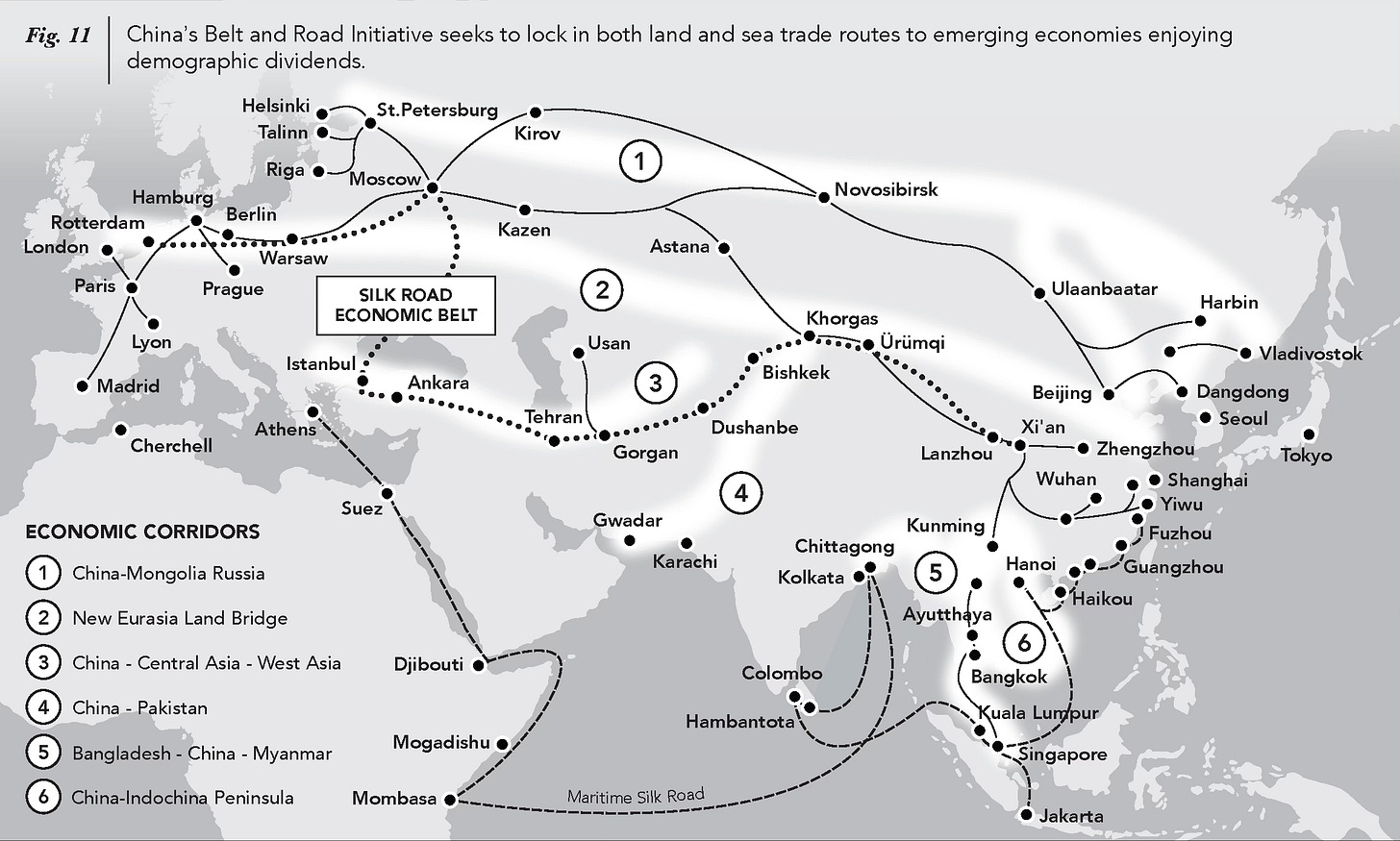

India’s journey from “world’s biggest democracy” to superpower status will naturally put a lot of its core pluralistic and tolerance values at risk. That much strikes me as inevitable. Why? India will inherently undergo several revolutionary developments at the same time: a huge demographic dividend of 500m souls, requiring massive job creation that must include accepting vast amounts of foreign direct investment and significant integration into global value chains — particularly those now dominated by China, which is widely viewed as seeking to encircle and capture India’s economy within its world-spanning Belt and Road Initiative that, quite literally, encircles India.

That is an arduous journey requiring both a strong state and a fairly coherent and unified society — two phenomena naturally addressed by the promotion of a vigorous nationalism.

Dangerous? You bet. Countries attempting that sort of rise have historically been highly susceptible to fascist and jingoistic impulses, particularly as their middle class swells. That is the historical experience of several rising powers across the 20th century.

Risers also tend to feature a lot of state domination. So, no surprise to hear that …

Government censorship of critical views has been on the rise. Social media platforms and other Big Tech firms, protective of their position in one of the world’s largest markets, have often given Modi and his allies what they want.

Given America’s now instinctive push to contain China’s rise — after decades of encouraging it, it’s also not weird to hear that …

Despite concerns over repression and accelerating autocracy, the Biden administration has been actively courting Modi, hoping that India can help contain Chinese expansionism in the Indo-Pacific region.

Piling on a bit, WAPO reminds us that India is not above assassinating those it considers to be significant bad actors (no pun there) operating abroad:

Canada’s explosive announcement on Sept. 18 that Indian government agents may have assassinated a Sikh separatist leader on Canadian soil underscores the uncomfortable choices the United States and other Western countries face in moving closer to Modi’s India.

As I noted in America’s New Map, that is a great power ruleset of our own making:

An awkward legacy of Obama’s GWOT makeover was his vigorous embrace of select killings of high-value targets—those enemies our government most wants dead. By doing so, America established precedents that competing great powers now readily exploit. Consider Putin’s targeted killings of Russian émigrés and defectors, Israel’s assassinations of senior Iranian government officials, and Saudi Arabia’s murdering of regime critics such as the journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

My noting that is not national self-flagellation but rather a reminder of our natural tendency to constantly hold other risers to standards that (a) we regularly transgress ourselves and/or (b) we ourselves only very recently began adhering to. Both hypocrisies involve our lack of historical awareness. Once our negative behavior slips into the past tense, it ceases to exist in our minds (genocide of First Nations peoples, for example). We are constantly white-washing our past (pun intended there).

So, easy for us to bemoan India’s current “culture of self-censorship” and how it has warped the streaming industry there — both foreign and domestic.

Simply put, every nation wants to manage content amidst all this invasive connectivity, especially as the former grows more extreme. For any rising power, this is nothing more than a matter of cyber sovereignty preserving social harmony. And it’s hard to blame them on the effort. Everybody’s got their own legitimate definition of cultural self-preservation.

It’s also a bit much for the US to scold India and others on this point, given how twisted our social and political discourse have grown, thanks in large part to social media and streaming platforms in general. Again, some self-awareness here would be good, and I do mean beyond noting the clear conflict of interest for Bezos’ WAPO to be working this righteous angle on behalf of its streaming parent. [The usual self-disclosure appears in graf #7, lest it be too much of an up-front turn-off.]

Once done with the top-of-story judgmentalism, the piece goes on, at length, to describe the censorship pressures exerted by the government on Amazon Prime and a particular Indian filmmaker.

No argument on the reporting, some queasiness on WAPO carrying Amazon’s water so openly, and a bit of disappointment that the paper doesn’t contextualize the Indian government’s response in terms of India’s “rising” journey versus the sad story of the thwarted filmmaker. It’s just too easy to paint India as “bad” this way, or losing its way.

Again, America made a similar journey with similar excesses, and we are still watching China work its own journey out. Someday both countries will feature far more wide-open and critical filmmaking, but to expect it now without accounting for the superpower-development journey that both remain on is a bit of a soda-straw perspective on their far larger and more complex reality.

It’s also a bit lazy and self-serving in terms of analysis.