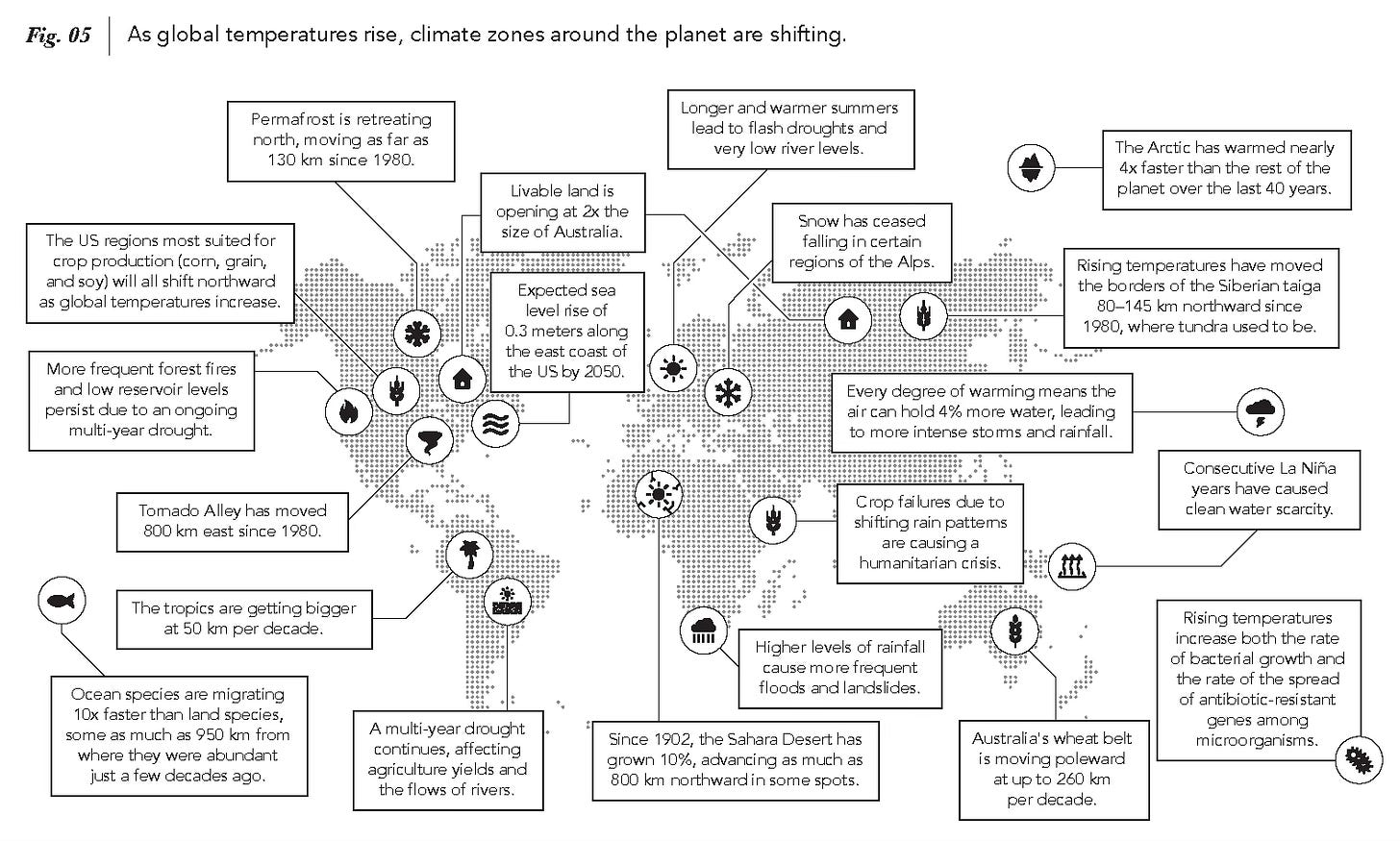

Climate change remaps the planet, shifting around climate with a velocity that grows over time. As I say in America’s New Map, climate velocity is “the rate and direction that climate shifts across Earth’s surface.” It is, by definition, disorienting. From the book:

Pragmatically speaking, climate change is most easily grasped like real estate, where the three most important rules are location, location, location. Climate change transforms our planet location by location, taking things long associated with one region and moving them somewhere different. What is happening may not seem unprecedented to you, but where it is happening should.

That’s the key thing to remember: none of this is unimaginable per se but it is often entirely new and thus disturbing to you, especially if you’re someone who’s lived their entire life in a specific clime. It’s like an invasion by the weather, along with species of all sorts (we tend to celebrate the benign ones and dread the nasty ones). It’s like all of life on this planet has been put in motion, because that’s what’s actually happening — a great re-ordering of nature.

Humans set that in motion with the Great Acceleration of activity associated with globalization’s spread:

Like evolution on steroids, climate change demands that all species— including us—adapt to environmental shifts that used to unfold over hundreds of thousands of years but now proceed in mere decades …

Thousands of studies indicate that most species, while furiously adapting, still fall behind the climate change curve … In general, species smaller in size, with shorter life spans and higher-frequency procreation, adapt better than larger, longer-lived species.

That means climate change is an evolutionary boon for parasites and pathogens—vectors of human disease. Invasive species can quickly devastate a local environment, rendering what once made it desirable into something dreadful. As a rule, parasites and pathogens stay put, but introduced to a new latitude, they opportunistically adapt to new hosts—the worst sort of evolution. Think about a recent local news story about some nasty species showing up in your backyard.

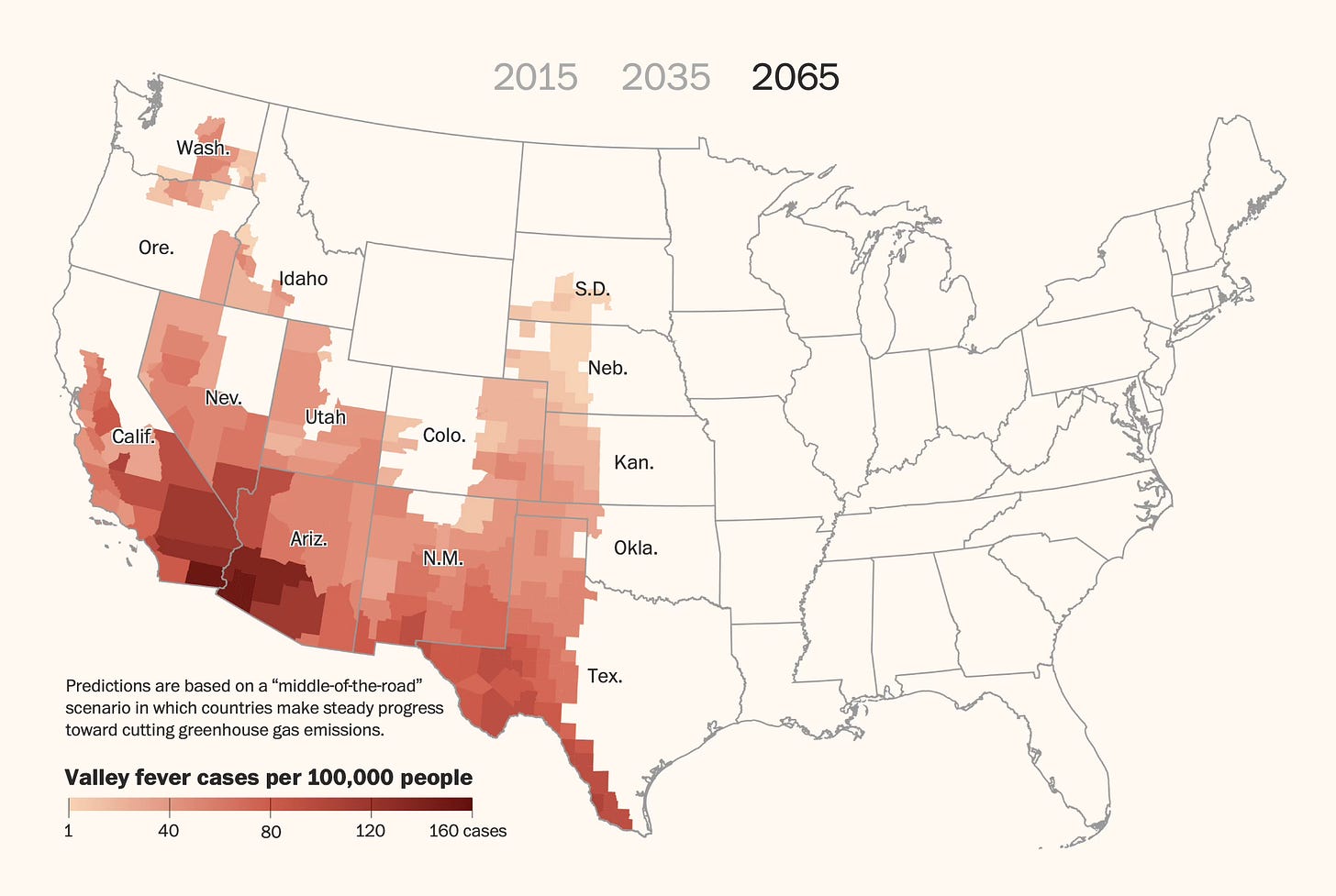

So here we find a WAPO story that gives us a practical example already impacting the United States: Valley Fever — a flesh-eating fungus that is spreading its geographic grip on the American West:

Valley fever has long haunted the American Southwest: Soldiers on dusty military bases, prisoners in wind-swept jails, construction workers pushing new suburbs farther into deserts have all encountered coccidioides, the flesh-eating fungus that causes Valley fever. But the threat is growing. Cases have roughly quadrupled over the past two decades, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A key reason for Valley fever’s spread, researchers say, may be human-driven climate change — and they warn that a much larger area of the United States will become vulnerable to the disease in the decades to come [emphasis mine]. The fungus thrives in dry soils, rides on plumes of dust and booms after periods of extreme drought — the exact cycles that scientists say have grown more intense and widespread across the American West due to the warming climate.

While science is not yet able to show a definitive link between the rising case counts and higher temperatures, the connection seems clear to many of the front-line health workers grappling with the disease.

“I cannot think of any other infection that is so closely entwined with climate change,” said Rasha Kuran, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of California at Los Angeles who is one of McIntyre’s doctors.

From a couple of maps, a sense of the geographic spread this century:

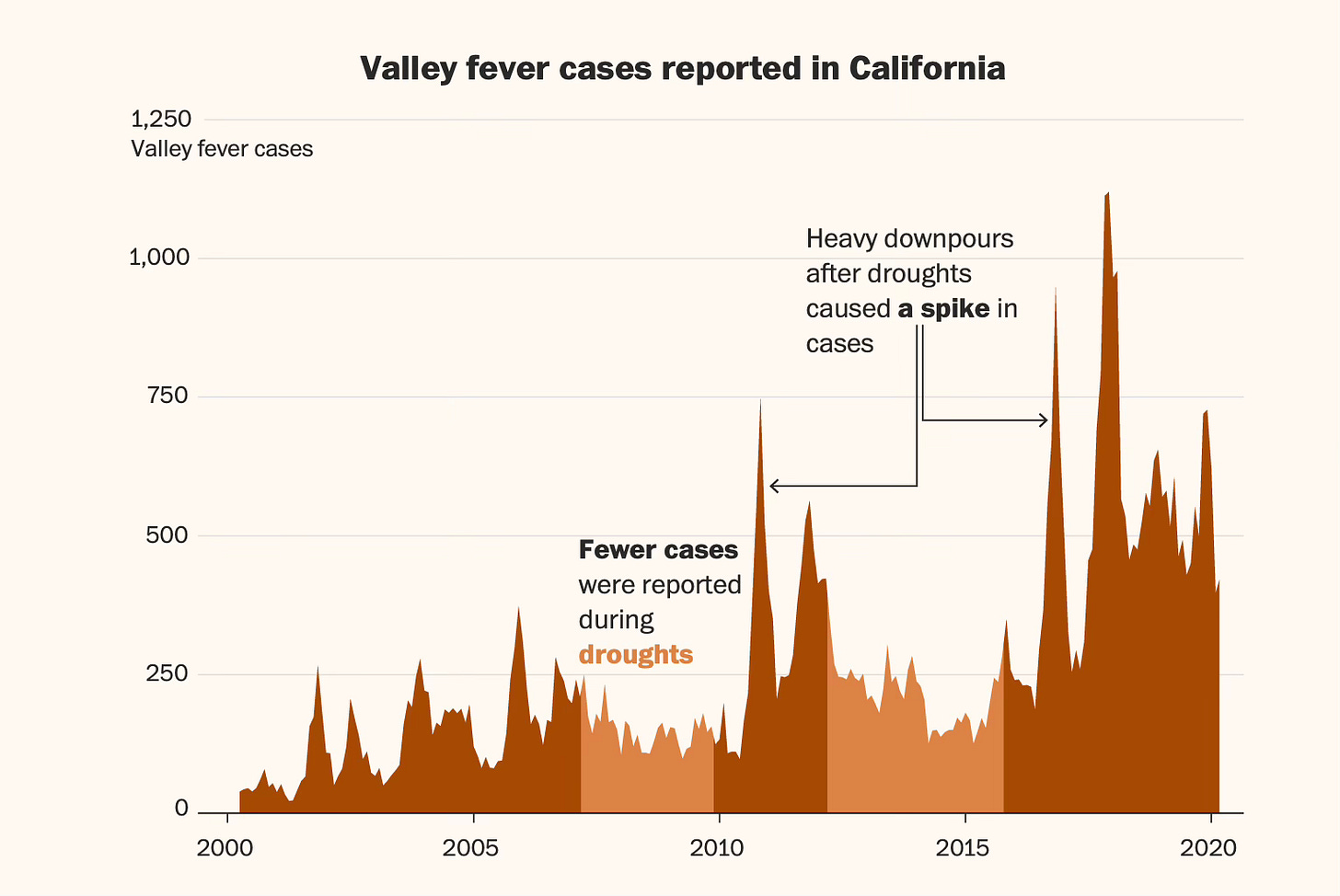

Like most of our climate change stories, this one speaks to complex causality: what really pumps up the spores that spread the fever is lots of drought disturbed every so often by torrential rains (that’s two out of the Four Horsemen of the Anthropocene — per author Gaia Vince; namely, drought and flood). See the WAPO chart below for the dynamic:

To me, this story is less about the sheer healthcare/research burden that naturally arises (covered in depth across the back half of the article), but about the inevitability of it all. Valley Fever’s expansive movement tracks with climate change; it signals a disease velocity that accompanies climate velocity. It’s all part of the they’re coming! dread that we as Americans suffer right now, with the they representing all manner of invasive change. We can single out immigrants but our fears are far larger. We can definitely turn on one another, blaming them! But we’re stuck with each other and all this change: a mixing of races and species and microbes beyond anyone’s control.

No kidding, but I think this growing dread is connected to, and reflected by, all the zombie stories out there in our mass media these past years. It has become a predominant theme of nature’s retribution.

So, if they’re coming (move), and we refuse to surrender (die), then all we’re left with is adapt, because America is getting a new map whether we like it or not.

From the WAPO piece, this is what truly caught my eye:

In the summer of 2010, a 15-year-old boy crashed his all-terrain vehicle on a dirt track amid the sagebrush in Eastern Washington, scraping up his legs. The next day, he swam in the Columbia River. Before long, he developed a fever and a swollen left knee.

At the time, Valley fever was not known to exist that far north … So when Heather Hill, an official in the Benton Franklin Health District, informed Washington state’s health department that this boy — and another 12-year-old who got sick around the same time — had tested positive via blood test for Valley fever but had no travel history to endemic areas, state authorities were skeptical.

“The department of health kept saying, ‘No, it’s impossible. Cocci hasn’t been seen any farther north than Northern California …

But when other clues emerged, Hill and state officials put on hazmat suits and returned to the site of the crash. With hand trowels and vials, they sampled rodent holes and surface soils. But the dirt stayed in a laboratory freezer for months while the CDC developed a test to confirm whether cocci was present.

Three years had passed by the time Hill finally received a call from Tom Chiller, a CDC official, confirming cocci was growing in the soil in Washington. It would be one of the most gratifying moments of her career.

“Heather,” he told her, “you just changed our map” [emphasis mine].

Just like when I wrote The Pentagon’s New Map two decades ago, that was my primary motivation in writing America’s New Map — a sense that our mental models of the world were growing out of synch with the underlying reality: maps undergoing great change.

To that end, let me leave you with some more maps from the great article:

We are living in a new age of discovery. We are learning that we must remap our political and economic world in response to how climate change is remapping the natural world. There is an undiscovered country out there — the radically evolved United States of America — awaiting our recognition and construction.

On that basis alone, it is an amazing time to be an American, because we are present at the creation of humanity’s next great evolutionary adaptation — one our country is uniquely prepared to lead.