As I like to argue, as Russia, China, and the US compete with one another, they see different game boards. We tend to be all about showdowns — typically over security but now also over trade wars (Trump to Zelensky: You don’t have the cards!). Russia is old school: throwing bodies (pawns) at whatever is the victim du jour. China, more strategic, extending networks slowly but surely throughout the non-Western world.

Different playing fields seen, resulting in very different strategies, but America tending toward the most transactional with Trump 2.0. We also tend to be the most top-down in our approach — leadership driven and summit-centric. China tends to be more bottom-up, facts on the ground, and incremental. Russia … always with the crudest possible angle — incredibly transparent in their goals even as they are the stealthiest in their means.

But, with Trump 2.0 now, all of them are acting or talking expansionism.

All very disturbing to Europe, with its troubled irredentist past. Then again, Europe has been the most active player out there these past 35 years, They were but 12 in 1990 and they are today 27, with ten in the pipeline.

Europe differs in style and tactics, to be sure, but it’s expansion nonetheless. Offered and conducted as free association and process-driven (metrics presented above), so, the best, by far, but only singular at this point in history because the US has, by and large, abandoned its old model of accepting new member states, with any talk of it typically freaking out the world with visions of brute-force conquering military campaigns (I know, we deeply resemble that remark).

By far, China’s approach remains the most ambitious, both in its own neighborhood and across the planet.

From America’s New Map:

Beijing, keen to present itself as law-abiding, nonetheless sits atop several thousand years of historic expansionism along its borders. In this never-ending endeavor, China has mastered what the West has dubbed “salami slicing” tactics (in Chinese, nibbling like a silkworm), wherein soft- and hard-power schemes combine to incrementally advance their lines of control in an unstoppable sovereign “velocity” not unlike climate change’s creeping advance.

A recent Wall Street Journal article counts the ways:

China Is Waging a ‘Gray Zone’ Campaign to Cement Power. Here’s How It Looks: Years of ship tracking data flight paths and satellite images show a clear intensification of Beijing's tactics across a swath of Asia

From the choppy waters to the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait to the frozen ridges of the Himalayas, China is pursuing a relentless campaign of expansion, operating in the hazy zone between war and peace to extend its power across Asia. Beijing carefully calibrates each move with the aim of staying below the threshold of action that could trigger outright conflict, but, step by incremental step, it has pushed deeper into contested areas, exhausting opponents and eroding their strength with 1000 cuts. Whether it is probes by warplanes maneuvers by Coast Guard ships or the creeping construction of new civilian settlements, China is constantly pushing boundaries of what security strategists call the grey zone. It tests the limits of what its opponents consider tolerable behavior, escalating a bit with every new action.

Is it China’s version of America’s Monroe Doctrine? On many levels, yeah.

In the South China Sea:

Island-building and militarization of artificial islands — in effect, literally creating ground as facts, and then generating facts on the ground

More frequent patrols by coast guard and maritime militia vessels

Suppressing other nations' similar efforts and thus asserting control over disputed areas

Outnumbering regional forces to maintain de facto control.

With Taiwan, the pattern is decades old: increasing air and naval incursions into Taiwan's air defense identification zone; conducting military exercises and patrols near Taiwan.

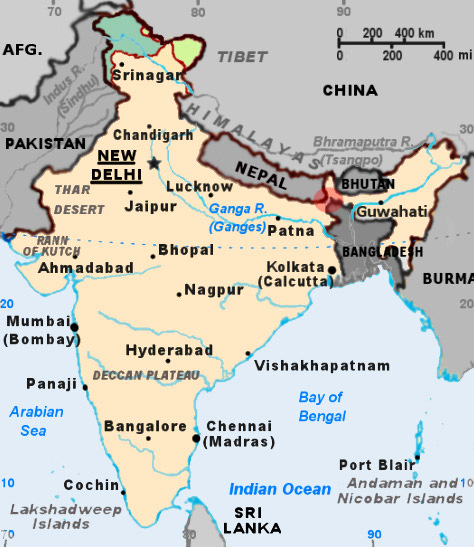

Touchiest is the disputed border with India (from my book):

India’s relationship with China is complicated by their long-disputed mountainous Himalayan border, where the two fought an intense but truncated war in 1962. India and China have never formally agreed on the matter, which is why they have engaged in countless skirmishes over the decades concerning the Line of Actual Control—a diplomatic oxymoron for a border suffering frequent incursions from both sides.

Elevating the matter in importance: China’s side of the border comprises the Tibet Autonomous Region annexed by Beijing in 1959. Mao Zedong famously intimated that China would eventually reclaim the “five fingers of Tibet”— namely, the independent border states Nepal and Bhutan, along with one Indian territory (Ladakh) and two Indian states (Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh).

If that was not enough, Tibet’s mountains are the starting point for seven rivers that flow into India—all subject to dam-construction and flow-diversion schemes pursued by an increasingly water-insecure China.

While talking the talk with New Delhi, Beijing nonetheless keeps establishing key outposts to challenge India's regional influence, creating, for example, settlements in Doklam, near the strategic Siliguri Corridor (that red spot connecting India to that hernia-like extension eastward)

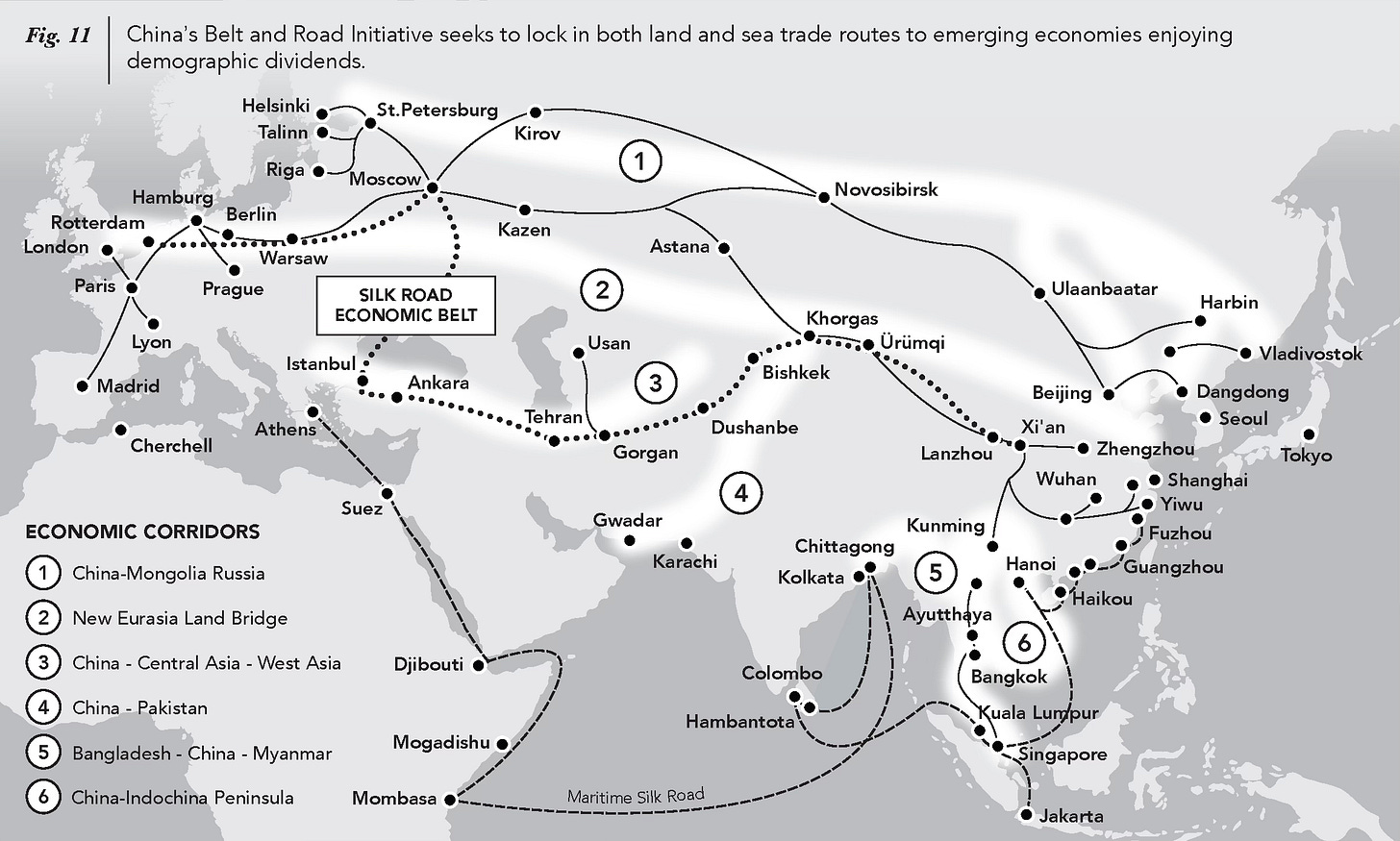

And, of course, we cannot forget China’s Belt and Road Initiative (from my book):

Two of China’s planned “economic corridors”— one to India’s west (involving fierce rival Pakistan) and the other to its east (linking Bangladesh, Myanmar, and India to Southern China)—effectively box in the subcontinent in conjunction with Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative. With all that going on, India’s clear reluctance to participate in China’s vast infrastructure schemes reminds one of Mexico’s lack of enthusiasm for financing Donald Trump’s border wall: it feels like an invitation to build one’s own prison cell.

India, naturally pushes back with its own quasi-expansionistic scheme:

It seems, does it not, that all five of our superpowers (US, EU, Russia, India, China) fear some encirclement.

The US is quite open about wanting to contain China in Asia. China literally encircles India with its BRI schemes. Russia fears NATO/EU encroachment, Europe fears the same in reply. America is now looking at Russian and Chinese ambitions in the Arctic, plus China’s growing influence across Latin America (which truly gets our attention) and Africa (now written off by the Trump Administration via the sacrificial death of USAID).

As I argued in the book: all five are acting or talking or just plain threatening their own “biggering.” Call it expansionism, or imperialism, or spheres of influence, or state-accession, or enlargement … whatever. The means differ but the ends are the same.

What does tell us about globalization’s next iteration?

It tells us that the world’s superpowers were comfortable enough with globalization’s rapid and stunning peak expansion period (1990-2008, but especially once America’s strategic attention was consumed by its 9/11 pivot to counter-terrorism) … until they weren’t. The Global Financial Crisis, coming on the heels of America feeling “quagmired” with its Global War on Terror, triggered the US awakening: Enough with the market-making where we “lose” and let’s get back to the ruthless market-playing, where we force wins in every bilateral relationship possible! (essentially mirror-imaging the bullying of Russia [overtly military] and China [nibbling like a silkworm]).

Nothing all that odd with this reversal: it’s very ten steps forward (1990-2008) and far fewer steps backward (since 2009).

What else triggered this re-regionalization?

China’s demographic dividend peaked in 2010, reducing the world’s rationale for sending everything there for assembly. The wage differential gone, globalization’s center of gravity has shifting to demo-divvying SE Asia. From there it shifts to India, and beyond that to Africa mid-century.

In other words, the great E-W integration impulse following the Cold War’s end came to its logical conclusion: Asia, now risen, largely produces for itself and majority trades with itself. Asia, particularly in the form of China, is now globalization’s integrator of record (BRI, etc.).

America is no longer in that business and was tired of it anyway, so our nation-building-at-home mantra shifts into high gear with Trump/MAGA, and with China going great guns around the world, Trump feels his inner Teddy Roosevelt kicking in.

From ANM:

No matter China’s success or failures, the United States is incentivized to limit those effects by offering something more strategically credible to those world regions it seeks to insulate from Beijing’s integration scheme. Since China’s debt-financed diplomacy resembles that of turn-of-the-twentieth-century European imperial powers, whose predatory behavior prompted Theodore Roosevelt to propose his economic corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, it is historically consistent to argue that America should make it a strategic priority to spare the Americas from either fate—but only by offering something more valuable in terms of security, prosperity, and affiliation.

China is presently on pace to become the single largest holder of sovereign debt in Latin America. If we cannot adequately outcompete China in our own hemisphere—an environment that gives us every strategic reason to do so—then there is little point in our attempting it on the other side of the world.

So no, Trump’s seemingly out-of-the-blue conversion to Teddy Roosevelt-ism did not surprise me. Like TR, Trump fears the “stationary state” (again, from ANM):

Fast-forward to the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893: America’s coming-out party as a world power. University of Wisconsin history professor Frederick Jackson Turner presents his “frontier thesis,” which traces American identity to its history of westward expansion. With that frontier now “closed,” fears spread that America would be swamped by, and lose its core identity to, an ongoing deluge of European immigrants, most of whom were then considered to be non-White.

Sound familiar?

Enter Theodore Roosevelt, self-invented Western cowboy. TR’s fears of the “stationary state,” in which Americans’ natural ambitions were boxed in by imperial powers claiming the world’s remaining frontiers, pushed him to declare an “open door” policy toward China, then being devoured by colonizing powers. It was the first time any US president had extended the Monroe Doctrine’s logic of curtailing European imperialism outside the Western Hemisphere.

In doing so, TR previewed the grand strategy employed by his cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the waning days of World War II: America would guarantee Europe’s access to global markets, preventing those nations’ imprisonment behind Moscow’s Iron Curtain.

That was our promise to the world post-WWII: we won’t let any hostile socialist competitor from the East (USSR, PRC) capture any “Western” market we consider too dear to lose (to include Japan, South Korea, and other Asian powers).

Were we fools with the whole “domino theory”?

Yes and no.

In many ways, and I stated this in the book, we were killing time in both Korea and Vietnam with those wars, waiting for our economic “win” to play itself out:

After World War II, America chose to simultaneously transform both elements with its vigorous, visionary leadership. We did not have to do this.

The Cold War obscured this stunning feat. That decades-long struggle featured various military wins, losses, and draws that—in the grand scheme of things—changed virtually nothing. America was simply waiting for the Soviet version of mini globalization to collapse in the face of our version’s immense success. When it did, our version of globalization went truly global, birthing the first majority global middle class—game, set, match alright, but not the “end of history.”

America’s challenge now is dealing with the success of this grand strategy, particularly the rise of competing powers. All five of our superpowers face their own particular trials this century: America struggling with its ongoing racial makeover; Europe contending with the Kremlin’s resurgent revanchism and, within its own ranks, incipient anti-immigrant fascism; deglobalized Russia being pulled into Beijing’s economic orbit as a vassal state; China scrambling to lock in its global holdings before succumbing to old age; and India hurtling toward a hard collision of demographics (its huge labor dividend) with climate change (stressing its agriculture-heavy workforce).

With all that going on, it is logical and reasonable to expect each competitor to seek a revision of global rules in its favor. After all, is that not what Donald Trump sought as president—however clumsily?

Why explain all this?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.