The cognitive dissonance suffered by Americans today is startling. By all normal macro measures, our economy is the envy of the world and yet most of us are unhappy with it — particularly our healthcare insurance system and the rising cost of housing. We’re suitably secure in our world but fear crime at home, even though it’s not high by historical standards. Nobody can adequately articulate where our country is headed and so the majority of us instinctively declare America to be off-track in poll after poll. We decry the decline of our rules-based world order and yet flagrantly violate its standards, not admitting our hypocrisy whatsoever. We are an intensely but evenly divided electorate, which means half of us are routinely rooting for America to fail on the other guy’s watch, which is nuts when you think about it. Compromise, the very essence of democracy, is despised by both ends of the political spectrum to a degree that is self-flagellating. As much as we hate and fear the wider world, we seem to hate and fear each other more.

It is a weird-yet-hugely-consequential time to be an American. The global order is changing around us, oftentimes ignoring us and our frequent and persistent manias. Everybody in the world seems disappointed with us and yet still instinctively turns to us on every big security issue — as though we have the magical capacity to prevent all wars or terrorism anywhere on the planet.

Now we have an inbound president who declares that only good things and no bad things will happen on my watch, which, of course, is pure nonsense and achievable only through the heavy employment of alternative facts (which no longer need to be checked by anybody, our courageous Tech Bros now declare).

And we wonder why our younger generations engage in so-called “doom spending” while our older generations fantasize openly about a return to the “golden age” of their youth.

There is a sleepwalking momentum to our national trajectory right now. After years of fighting a noun (terror), we now aspire only to achieve an adjective (great). You can’t call it style over substance because there is no substance — just grievances and fear and loathing.

It seems an impossible time for grand strategic visions or even the kernel of national purpose (which would logically focus us on adapting to, and moderating, climate change — goals that dovetail nicely with technological advances).

In the absence of such vision and/or purpose, we just don’t seem to know who we are anymore.

What kind of American are you?

Hmm.

I always try to write as I feel, meaning I really want to believe in what I’m putting down in “print” — authenticity. And I authentically do not feel particularly optimistic about this year.

Stock traders often note that the market’s performance over the first few days of the year typically indicates what’s possible/likely for the rest of the year — the so-called January Barometer. If that’s true this year, then we’re looking at a year of significant volatility and mixed wins/losses, and that feels about right.

Trump definitely has opportunities to effect great change and ambitions to do so, and yet, he’s not a follow-through guy on legislation — at least not like Biden was. So, besides the usual tax cuts, budget cuts, and deconstruction of the “administrative state” promised by MAGA, it’s hard to see this new administration accomplishing a whole lot other than demanding the times be declared “good” — no matter the actual trajectory. Thus I suspect we’ll get a lot of feel-good measures (Hello, Gulf of America!) and a big party in 2026 but no new clear sense of where we’re headed as a nation — much less as a world we now mostly disavow.

That’s me on a low note, alright, which perhaps is why I glommed onto Michael Beckley’s ambitious and comprehensive piece in the current Foreign Affairs entitled, “The Strange Triumph of a Broken America: Why Power Abroad Comes With Dysfunction at Home.” I mean, it seems to get at that cognitive dissonance, does it not?

Beckley starts off by noting the incredible range of diagnoses out there right now when it comes to a dysfunctional America:

Some scholars draw parallels between the United States and Weimar Germany. Others liken the United States to the Soviet Union in its final years—a brittle gerontocracy rotting from within. Still others argue that the country is on the brink of civil war.

Some choice, huh?

Beckley’s primary point: when you compare us to the competition out there, we doing pretty damn well, meaning there’s really nobody out there that we’d rather trade places with.

This is the paradox of American power: the United States is a divided country, perpetually perceived as in decline, yet it consistently remains the wealthiest and most powerful state in the world—leaving competitors behind.

It’s a meh message about a meh country: in effect, This is as good as it gets right now!

Depressing, right?

Beckley best paragraph in the entire piece:

How can such dominance emerge from disorder? The answer is that the United States’ main assets—its vast land, dynamic demographics, and decentralized political institutions—also create severe liabilities. On the one hand, the country is an economic citadel, packed with resources and blessed by ocean borders that shield it from invasion while connecting it to global trade. Unlike its rivals, whose populations are shrinking, the United States enjoys a growing workforce, buoyed by high levels of immigration. And despite political gridlock in Washington, the country’s decentralized system empowers a dynamic private sector that adopts innovations faster than its competitors. These structural advantages keep the United States ahead—even as its politicians squabble.

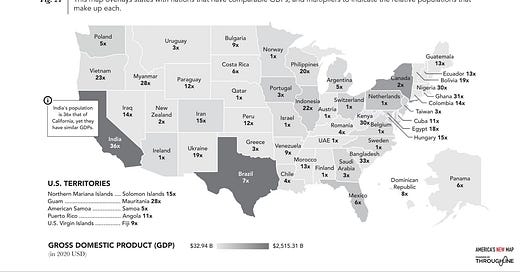

Structural advantages? You don’t hear much about those nowadays, even as I tout that argument myself quite vehemently in my “The West is the Best” (Throughline Six) presentation in America’s New Map.

Beckley does a nice job of describing those structural advantages, but they come, as he notes, with two terrible handicaps: first, the urban-rural divide (aka, Blue State-v-Red State, coastal-elites-v-fly-over-country, globalizers-v-globalization-victims, etc.); second, the insulating effect of our wealth and geography that — and here’s where he loses me somewhat — cause us to underinvest in our military and diplomatic capabilities, thus resulting “in a hollow internationalism in which the United States seeks to lead on the world stage but often lacks the resources to fully achieve its goals, inadvertently fueling costly conflicts.”

First off, it’s hard to say we don’t spend enough on our military — relative to the world, or that its performance is eclipsed by any national force out there (except maybe Ukrainian drone operators right now). Sure, you can gripe about not spending what we used to spend during the Cold War on diplomatic efforts and capabilities, but is that really an explanation for the above criticism? Our military and diplomatic underspending inadvertently fuels costly conflicts around the world?

There is a presumed responsibility there generating phantom cause-and-effect dynamics in Beckley’s analysis

A long section then ensues, detailing all the ways America remains an “economic powerhouse.” As for economic weaknesses, “they are generally less severe than those of other major economies.”

Agreed.

I look at what China needs to achieve over the next three decades and the internal resources it can muster toward those ends and I like our chances plenty. We’re good on food, education, the dollar as the world’s largest reserve currency by far, energy production, and innovation most of all.

I take back what I said earlier; these two grafs are Beckley’s best:

Critics contend that the United States is a house of cards, its towering strength masking a faltering foundation. They point to government gridlock, eroding public trust, and deepening societal divides as cracks spreading through the civic bedrock—fractures they claim will inevitably undermine the pillars of U.S. wealth and power.

Yet U.S. history shows no straightforward link between internal turmoil and geopolitical decline. In fact, the United States has often emerged stronger from political crises. The Civil War was followed by Reconstruction and an industrial boom. After the financial panics of the 1890s, Washington became a world power. The Great Depression spurred the New Deal; World War II marked the beginning of the “American century,” an era of unprecedented U.S. primacy. The malaise of the 1970s, marked by stagflation, social unrest, and defeats in Vietnam and Iran, eventually gave way to a resurgence in economic and military strength, a Cold War victory, and the tech boom of the 1990s. In the early years of this century, disastrous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, combined with the Great Recession, fueled predictions of U.S. decline. Yet nearly 20 years later, the American century rolls on.

This is, in my opinion, very dialectical thinking: strength battles weakness and out of that struggle comes new and better answers (synthesis). What Marx got wrong was doubting the ability of democracies to self-correct. Easy mistake for him to make, concentrating his gaze on industrial, imperial Britain of the 19th century. The Victorians did not bend and so ultimately broke.

Then, Beckley delivers what should be a cautious note for the Trump Administration:

Although the U.S. political system often seems gridlocked, its decentralized structure—distributing authority across federal, state, and local levels—empowers a workforce that is more educated than those of China, Japan, Russia, and the United Kingdom. Unlike most liberal democracies, which developed strong states before democratizing, the United States was born a democracy and only began building a modern bureaucracy in the 1880s. The American constitutional system, designed to maximize liberty and limit government, constrains state capacity but facilitates commerce.

Ah, the virtues of what is now maligned as the “deep state.” We’ll see how much lasting damage Trump triggers within one of our nation’s greatest advantages over the competition.

Beckley continues with an ode to American innovation, offering the reassuring argument (which I agree with) that China’s state-led innovation cannot possibly prevail over our private-sector-led innovation-heavy industries. Winners must emerge; they cannot be picked from on high by bureaucrats. It’s not what the latter are good for.

In reiterating his argument about our disabling urban-rural divide, Beckley makes a great point that any careful observers have long noted about the American system: the rural parts depend on government support far more than the urban centers. This is the hard-stop obstacle to the MAGA fever dream about killing government and unleashing “freedom.” Freedom from want (H/T FDR) is still a biggie in an economy featuring its highest levels of wealth inequality since the Gilded Age.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.