Globalization and Climate Change Sitting in a Tree...

Where is the love? Because they are joined at the hip.

With Biden meeting Xi at the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Coordination) summit in San Fran last week, WAPO made a push (board editorial plus an outsider’s op-ed) to highlight just how much the world needs globalization’s help in tackling climate change. I found the combination to be an unusually intelligent and broad framing of these highly interrelated issues.

In America’s New Map, I pretty much say that climate change is the price tag of US-style globalization, whose primary good was the creation — for the first time in human history — of a majority global middle class. Was it worth it? Hell, yeah.

There is no denying globalization’s role in spiking these global crises, but we must reject the hindsight that their emergence invalidates America’s strategy of encouraging globalization’s poverty-eradicating advance. We made the world an infinitely better place that now faces new challenges. Who can argue that humanity’s economic betterment should have been denied— despite these costs?

As I have argued throughout all my books, you can’t expect the poor to value the environment more than their survival or their advancement out of sheer poverty. That’s just unrealistic and immoral, in my opinion.

If you want them to really care about the environment, then first get them into a position of caring about it (namely, enable their rise to middle-class status) and then provide them the means to do so (typically foreign direct investment [FDI] that sees enough certainty in those targeted futures to warrant the risk). How do you create such certainty? Foreign aid has a weak record on such reforms. Instead, as I argue in America’s New Map, one must offer the geopolitics of belonging.

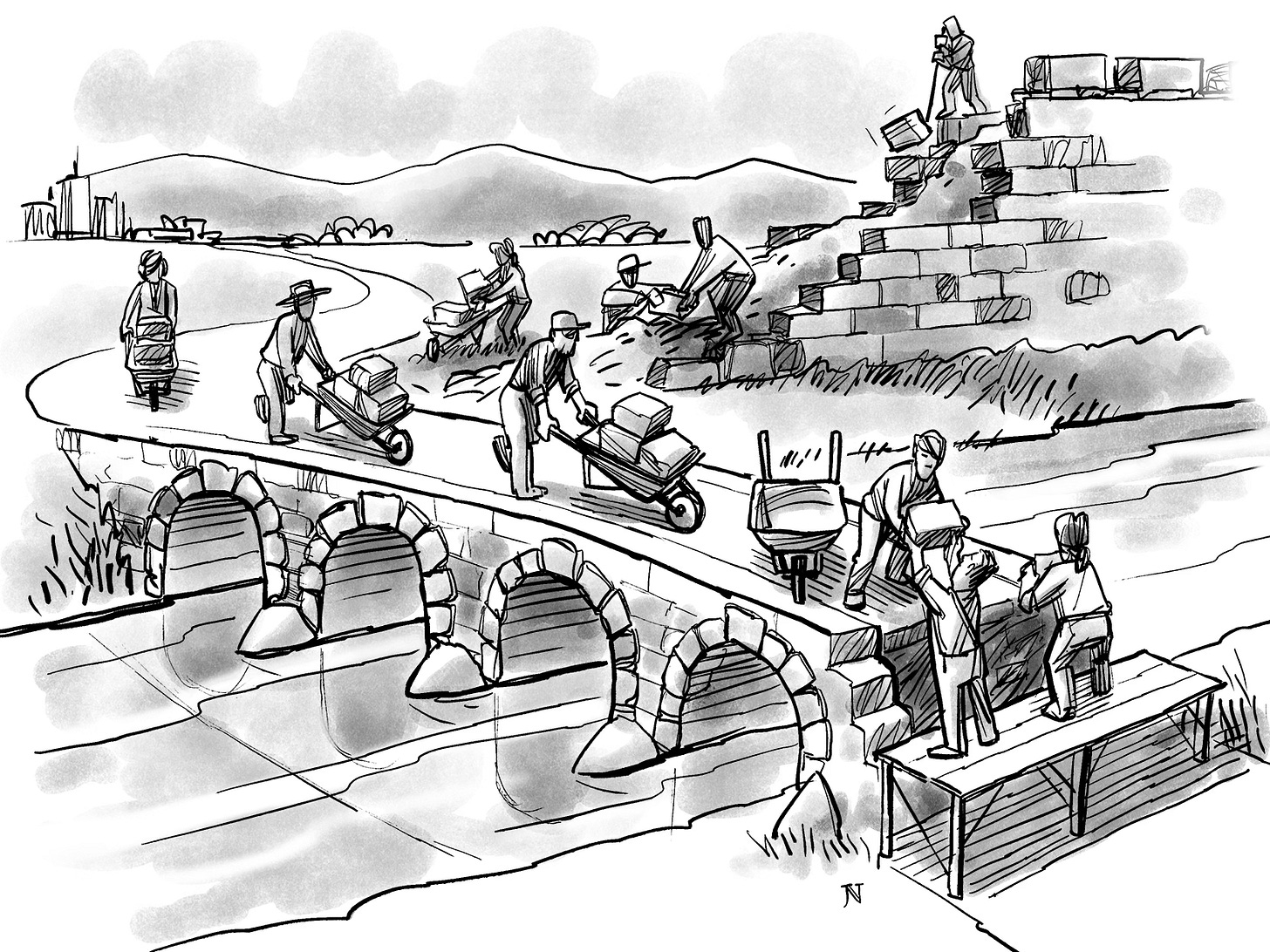

Our choice of bridges versus walls is a powerful signal to our Southern neighbors, the former indicating our openness to salvaging as much of Middle Earth as possible to sustain viable statehood there. Better to link infrastructure development to a pathway for eventual membership in expanding North-South political unions than to simply hand over trillions of dollars in a UN-sponsored global “loss and damage fund” certain to aggravate the North’s angry populism while succumbing to all manner of waste, fraud, and abuse at the hands of local governments ill equipped to manage such spending. By signaling such long- term political intentions, the North creates a far more secure investing environment to the benefit of all. In other words, an effective response here focuses on incentivizing and mobilizing the private sector more than the public sector.

This is where the confluence of climate change and an ascendant global middle class creates a unique historical opportunity: climate change generates geopolitical “orphans” (non-viable states, migrants) at exactly the point when that South-centric middle class seeks maximum belonging (protection of newly acquired status and wealth). That tectonic collision of fear and hope defines this century, demanding that superpowers mov beyond their strategic fixation on national defense and embrace a far more expansive definition—and delivery— of security in all its forms.

Exporting security isn’t the same as exporting defense (arms sales). It’s about creating that certainty of belonging, something the EU offers in political form with its state-accession model and something China offers in economic form with its Belt and Road Initiative.

What does America offer right now — beside sanctions? Trump’s warmed-over protectionism, for the most part (say it isn’t so, Joe!), hence the warnings from the WAPO board about leveraging globalization in the service of addressing climate change.

From the editorial:

The Biden administration has offered reasons to justify reorganizing the world economy: to prevent China from accessing some high-end technologies; to reduce the inherent risk in far-flung global supply chains; to bring jobs home.

The objectives might have merit. But pursuing them comes at a cost: Most notably, the trade restrictions the United States has deployed to promote this new world order are slowing the fight against climate change.

First, it cuts off our access to cheaper solutions produced abroad.

At home, protectionist policies slow clean energy deployment. For instance, China produces about 4 in 5 solar photovoltaic cells and modules.

Second, by de-optimizing global value chains, any continued trade war with China invariably boosts both their and our emissions.

Modeling by researchers in China, the Netherlands and Denmark found that global greenhouse gas emissions would rise by up to 1.8 percent if the United States and China stopped trading. This increase would be mostly driven by a jump in Chinese emissions and increases along the value chain in other Asian countries due to the shift of exports and imports to different markets and suppliers.

The example dearest to my heart:

Consider the early days of the trade war: In 2018, China responded to U.S. tariffs by raising barriers against American soybeans. U.S. exports to China tumbled. Brazilian soybean exports picked up the slack. And rainforest deforestation — fueled to a great extent by demand for soybean acreage — reached its highest level in a decade, adding to Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“The Amazon rainforest could become the greatest casualty of the U.S.-China trade war,” wrote a group of alarmed scientists from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and the University of Edinburgh.

Third, America should want the green techs we develop as a result of Biden’s ambitious Inflation Reduction Act to flow freely around the world (making us money in the process ….).

Technology diffusion will make the climate transition cheaper in rich and poor economies alike. Research and development travel along value chains, pushing innovation across trading partners. One study estimated that the carbon price required for a given amount of CO2 reduction would be 16 percent to 47 percent cheaper in a world with knowledge diffusion than in a fragmented world.

By far too-much continuing Trump’s protectionism, Biden has us misbehaving in a system of our creation — transgressing its most essential rule just as the world confronts a true global crisis destined to place our nation’s entire economic fortune at risk.

In sum, says WAPO, we should be leading, not lagging.

Fighting climate change requires the best green-energy technologies be deployed quickly and widely. For the sake of the planet, the United States should seek to keep global exchange as open as possible.

The accompanying op-ed is good as well, just more trade-detailed in its logic.

What I take from both is what I argue in America’s New Map: the two dynamics are so interrelated as to be inseparable. Preserving globalization is preserving the just-emerged majority global middle class. Does anyone think we’re going to “solve” climate change in defiance of their goals, dreams, ambitions, fears, etc.?

No, we’re going to navigate climate change primarily by 1) first ensuring that global middle class’s continued standard of living (lest political instability ensue) and 2) better shaping — in environmental terms — that global middle class’s underlying consumption pattern (not confusing consumption with standard of living because they are not the same).

We have no hope of achieving either in a more fractured world. Our only realistic choice is to embrace radically more interdependence, or, as I put it in my book, profound North-South integration.

Radical interdependence.

That’s how America got so rich across its cohort of now 50 member states, and that’s how we’re going to stay rich — despite climate change.

We get better by getting bigger — just as we have throughout our history.