Going gray on a global scale

Eberstadt weighs in on a key component of my American grand strategy

Nicholas Eberstadt is sort of the King Kong of demographers, so, when I see him swatting at planes atop the Empire State Building, I pay attention.

His latest in FOREIGN AFFAIRS.

No huge surprises: the whole world is aging as fertility systematically drops around the world and people live longer. In the advanced North (to include China), that already translates into depopulation dynamics, meaning countries that have never really welcomed immigrants (think China, South Korea, Japan) are beginning to realize that this is going to be a big long-term problem for them (too few workers providing for too many dependents [mostly old]).

Eberstadt:

With birthrates plummeting, more and more societies are heading into an era of pervasive and indefinite depopulation, one that will eventually encompass the whole planet. What lies ahead is a world made up of shrinking and aging societies. Net mortality—when a society experiences more deaths than births—will likewise become the new norm. Driven by an unrelenting collapse in fertility, family structures and living arrangements heretofore imagined only in science fiction novels will become commonplace, unremarkable features of everyday life.

Childless cat ladies are becoming more than a political accusation; they are redefining family and society

We have depopulated as a species before, notes Eberstadt, citing the Black Death of the 1300s. But we’ve been on a 20-fold increase since then and we’ve organized so much of our economy and society around that. Now, we will face inconceivable mismatches.

One I would cite already: traditional churches losing numbers because what they preach doesn’t match the world these younger people find themselves inhabiting — much less anticipating. Religions will adapt or fade, like so many other things — and species — being pushed to the brink nowadays by climate change’s pervasive and profound remaking of our planet.

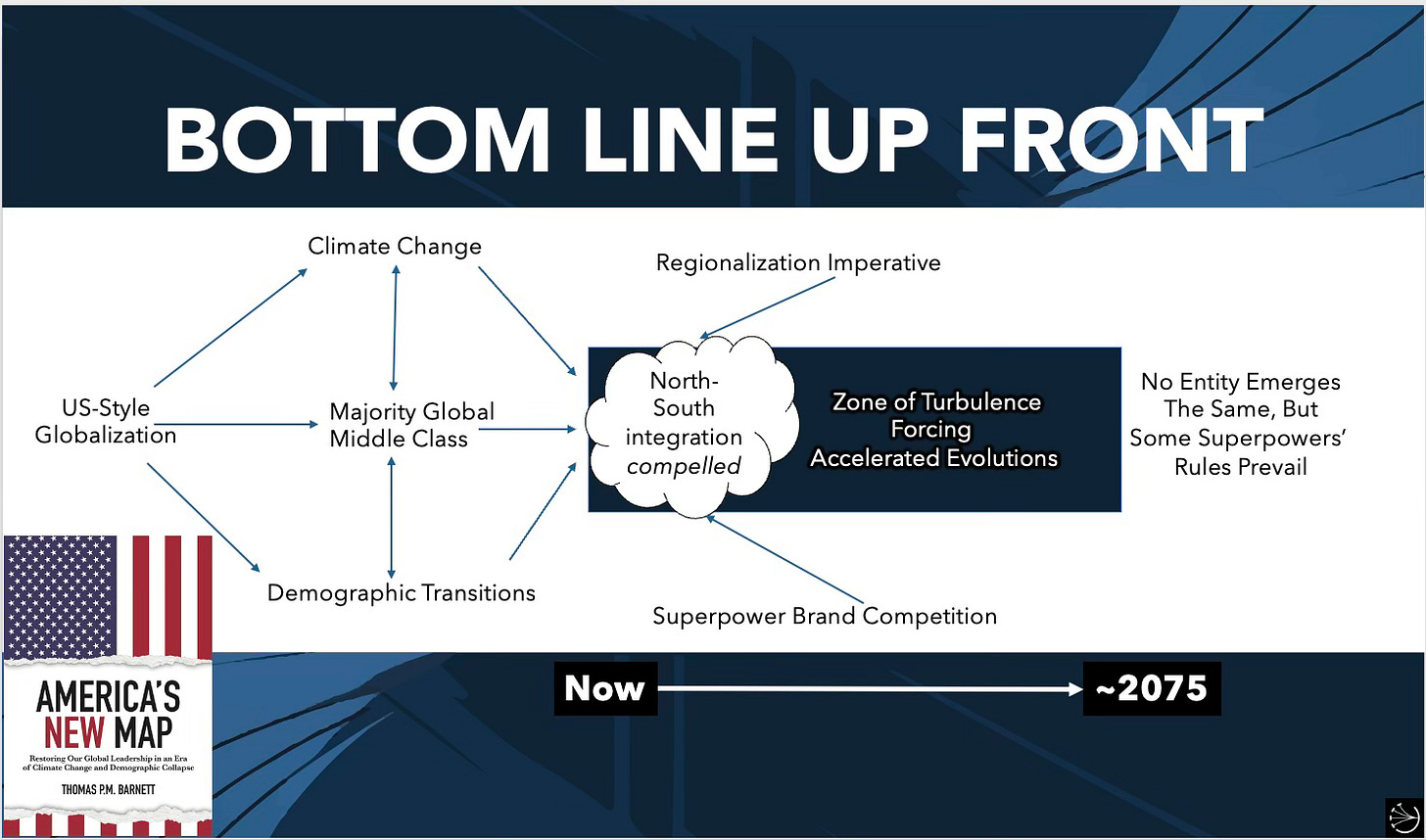

Per my argument: we enter a half-century of turbulence driven by the combination of climate change (very North-South differentiating) and demographic collapse (likewise). The wild-card collision careening through both? Roughly 3B joining (or at least attempting to join) a global middle class: either finding that to be a great thing or a very tenuous thing because of the societal, environmental, economic, security, and political makeovers triggered by those climatic and demographic waves of change.

Mimicking Eberstadt’s logic, evolutionary velocity picks up dramatically in an adapt, move, or die world undergoing great change. If scientists declare that climate change asks the world’s species to evolve at roughly 10,000 times normal rate, then, yeah, EVERYTHING IS GOING TO CHANGE AT HIGH SPEED OR COLLAPSE/DISAPPEAR.

This is the world we’ve leaving behind — us Boomers, and our political leadership response to-date has been woeful — almost criminally so.

Back to Eberstadt:

The last global depopulation was reversed by procreative power once the Black Death ran its course. This time around, a dearth of procreative power is the cause of humanity’s dwindling numbers, a first in the history of the species. A revolutionary force drives the impending depopulation: a worldwide reduction in the desire for children.

As I put it in America’s New Map:

For most of human history, we adhered to the basic directive governing all species—maximum procreation. Numbers ensured survival, so we structured the foundations of our societies around that goal, in particular organized religion. Until very recently in history, this approach was entirely warranted. Preindustrial societies featured both high birth and death rates—a never-ending race to stay ahead of extinction’s many enablers (e.g., disease, famine, pestilence, war).

But once industrialization takes root, it forever alters that primordial calculation. Improvements in farming drive laborers to cities, where advances in medicine—particularly vaccines—render early childhood less treacherous to navigate. Babies start making it to age five at far higher rates, dramatically extending life expectancy for society as a whole.

As the death rate declines, families follow suit on procreation. Once urbanized, it is no longer crucial to maximize the number of children, who shift from a family asset on the farm (more hands) to a family liability in town (more mouths). Women enter the workforce and gain access to reproductive controls, further depressing fertility. A new mindset emerges—family planning.

There is no going back once this point of development is reached. Doesn’t matter the local culture; the same dynamics appear everywhere.

Like me, Eberstadt predicts that all governmental attempts to boost fertility will fail. They’ve just never worked out anywhere — the closest success being Ceaucescu’s disastrous efforts in Romania in the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s (the infamous 1966 Decree 7700), which only yielded a “lost” generational wave of poorly educated/fed/treated/etc. workers and orphans. It was a sad, tragic lesson of how one country can trigger and monumentally abuse a demographic dividend (a good part of my PhD diss, BTW).

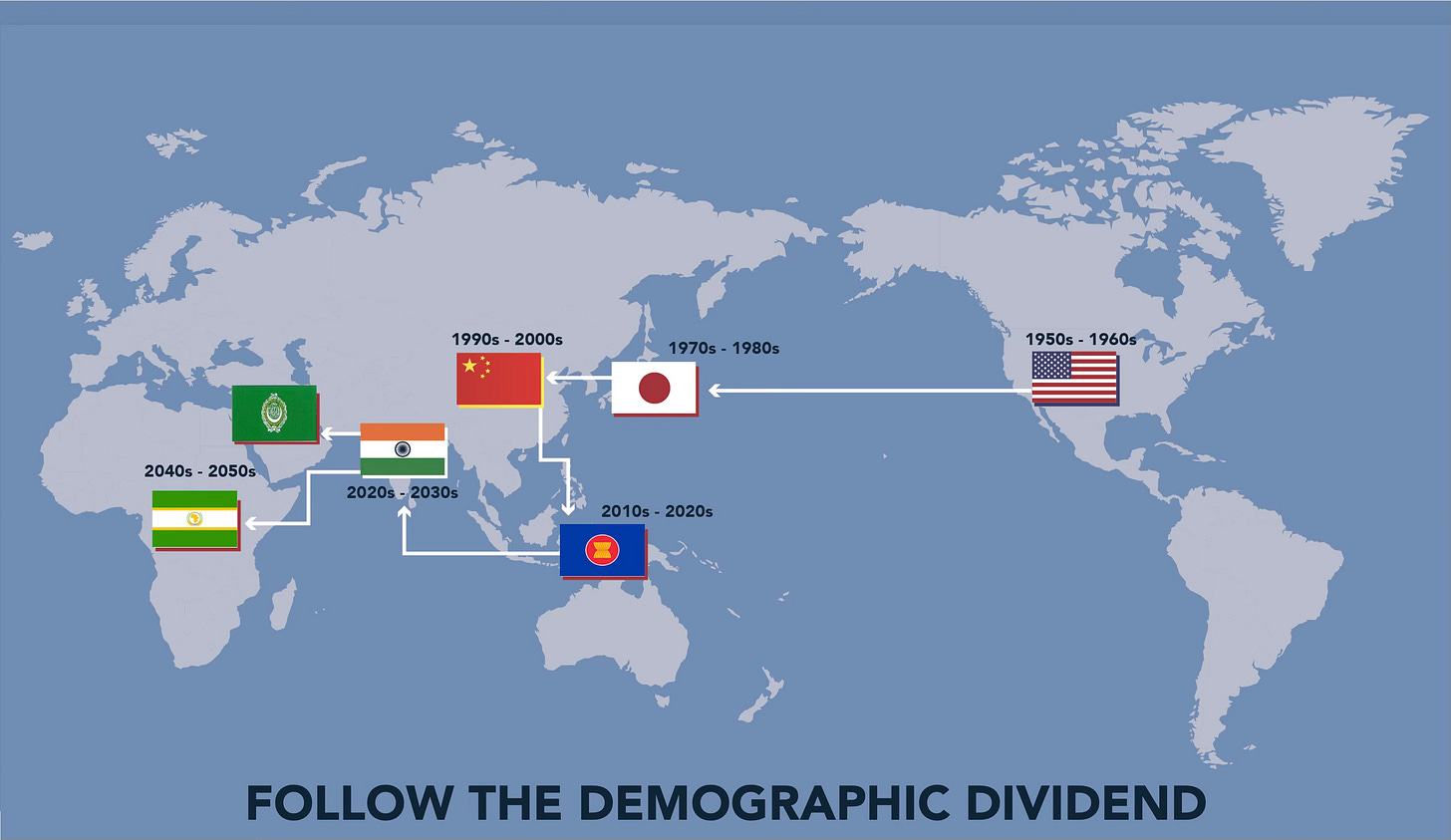

Anyway, that die has been cast — largely thanks to the worldwide economic development unleashed by US-style trade and integration dynamics that we now label “globalization.” That journey from farm to factory that I summarized above? That is the price of admission to global value chains: your nation’s moment in the demographic “sun” that must be exploited, with your ultimate prize being an advanced-but-rapidly-aging society.

Unless … you’re the United States. Per Eberstadt:

The United States remains the main outlier among developed countries, resisting the trend of depopulation. With relatively high fertility levels for a rich country (although far below replacement—just over 1.6 births per woman in 2023) and steady inflows of immigrants, the United States has exhibited what I termed in these pages in 2019 “American demographic exceptionalism.” But even in the United States, depopulation is no longer unthinkable. Last year, the Census Bureau projected that the U.S. population would peak around 2080 and head into a continuous decline thereafter.

So, what to do with this longer runway?

Why, lengthen it, of course.

The most obvious way to lengthen it is some combination of letting in more immigrants (hard) and/or merging with younger populations (like to our South).

My argument/prediction/warning is that America will end up doing both. This is why the cover of my book features an American flag with something around 150-160 stars.

Open the kingdom, say I. Bulk up to match the consumer power of an expanding EU, a huge China, and a huge India. Get bigger and get better, like we have throughout our history.

In short, get back to where we once belonged.

Because we know where the world is going in terms of fertility:

The only major remaining bastion against the global wave of sub-replacement levels of childbearing is sub-Saharan Africa. With its roughly 1.2 billion people and a UNPD-projected average fertility rate of 4.3 births per woman today, the region is the planet’s last consequential redoubt of the fertility patterns that characterized low-income countries during the population explosion of the middle half of the twentieth century.

China to India to Africa becomes the globalization/demographic equivalent of Tinkers to Evers to Chance.

Eberstadt makes the argument of human (female) agency in determining the ongoing baby bust, pushing aside economic development and modernization, but I find this distinction without meaning: economic development and modernization is what gets you female agency — either directly or by revealed example.

Still, I agree with the notion “discovered” (or just noticed!) three decades ago, as described by Eberstadt:

Eventually, in 1994, the economist Lant Pritchett discovered the most powerful national fertility predictor ever detected. That decisive factor turned out to be simple: what women want. Because survey data conventionally focus on female fertility preferences, not those of their husbands or partners, scholars know much more about women’s desire for children than men’s. Pritchett determined that there is an almost one-to-one correspondence around the world between national fertility levels and the number of babies women say they want to have. This finding underscored the central role of volition—of human agency—in fertility patterns.

Here’s how I put much the same logic down in ANM:

Fertility is primarily determined by what happens with girls and women when economic development takes root. If you want a demographic dividend, keep girls in school for as long as possible. It is as simple as that. Better-educated women have fewer kids, who in turn are themselves better educated—an economic win-win. Conversely, the easiest way to sabotage a dividend is to marry off young girls or mandate forced births. Capturing the full demographic dividend requires investment in human capital.

Eberstadt’s point is that even women in poor countries are embracing this agency over time, which he interprets — unsurprisingly — in terms suggesting that the power of example here extends beyond advanced economies into less advanced economies, the so-called “flight from marriage” by women being a big one. But, to me, even there we’re really talking the power of economic development and modernization because it’s that promise/aspiration/ambition that is turning these women’s heads even in less developed economies.

The cat is out of the bag and in that single lady’s apartment!

Simply put, the female code of getting ahead has been cracked and it’s not really a secret anywhere in the world where it is allowed to naturally play itself out.

As for when global population peaks? My proposed 2075 tipping point sits smack dab in the middle of most projections — for now, meaning basically that all of my kids (born 1991, 1995, 2000, 2003, 2006, and 2008) could easily live to witness that momentous day. [I will definitely have to work for that privilege.]

So, not so much a theory to them but an inevitability to be anticipated by whatever means necessary.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.