Here come the South Asians

The renewed international student wave recalls the flood of Chinese college students to US universities back in the day.

India’s clear replication of China’s rise — while there will always remain key differences reflecting the evolution of globalization in the meantime — continues to unfold. Now we are informed by WAPO that, not only has the flow of international students to US universities and college resumed its pre-COVID heights (thus reaffirming America’s unparalleled brand appeal on that score), but the resumed crush is being led by an explosion of South Asian students.

Here goes:

Fueled by record numbers from India and other South Asian countries, the head count of international students at U.S. colleges and universities and in related training programs has surged at the fastest growth rate in more than 40 years and recovered almost all the ground lost during the coronavirus pandemic.

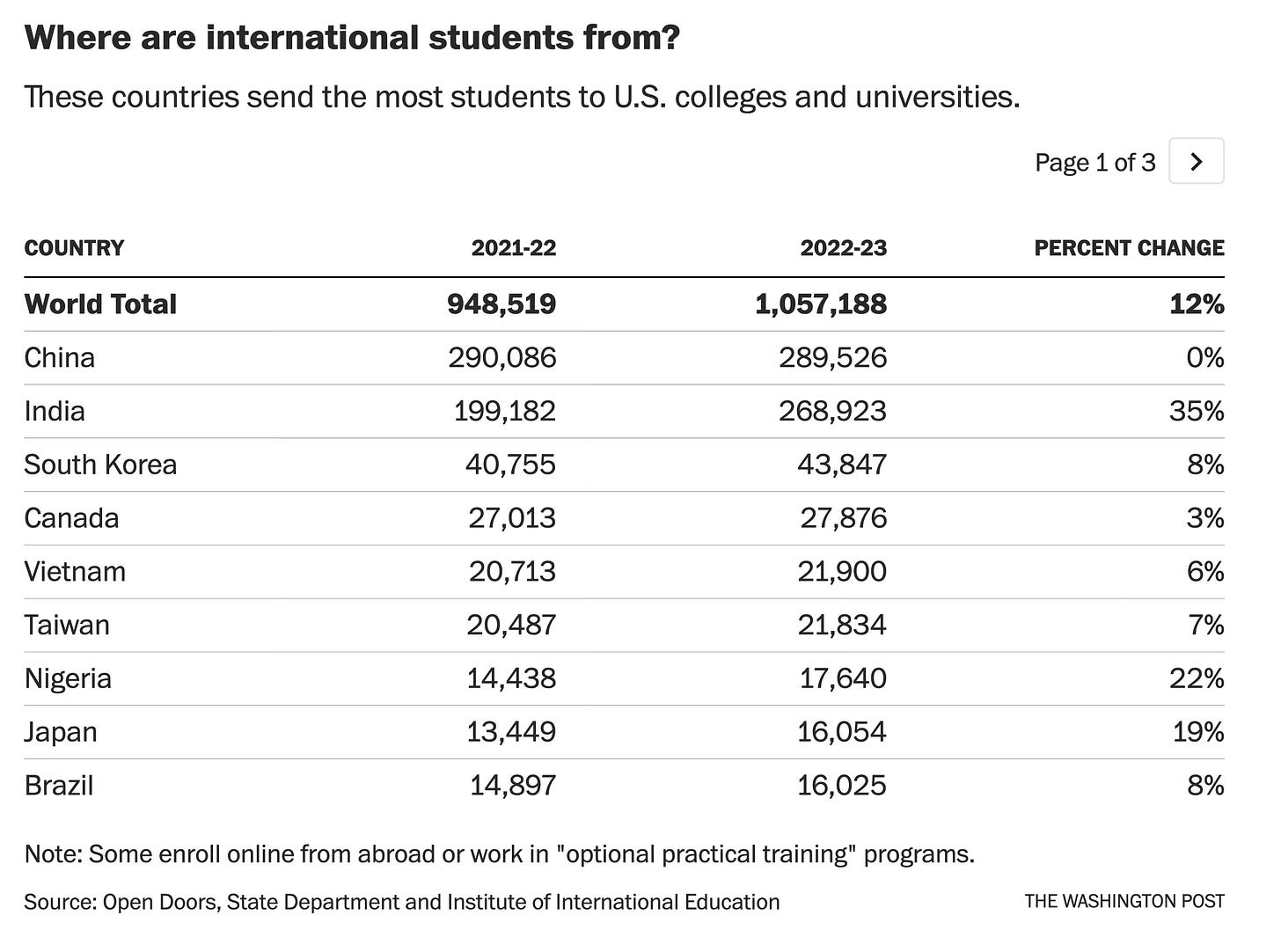

A report released Monday found 1,057,188 international students in the U.S. higher education system during the 2022-23 school year, up nearly 12 percent from the previous year. Not since the late 1970s has the total grown that much in one year. These students bring global perspectives to campuses and account for more than 5 percent of postsecondary enrollment in the United States.

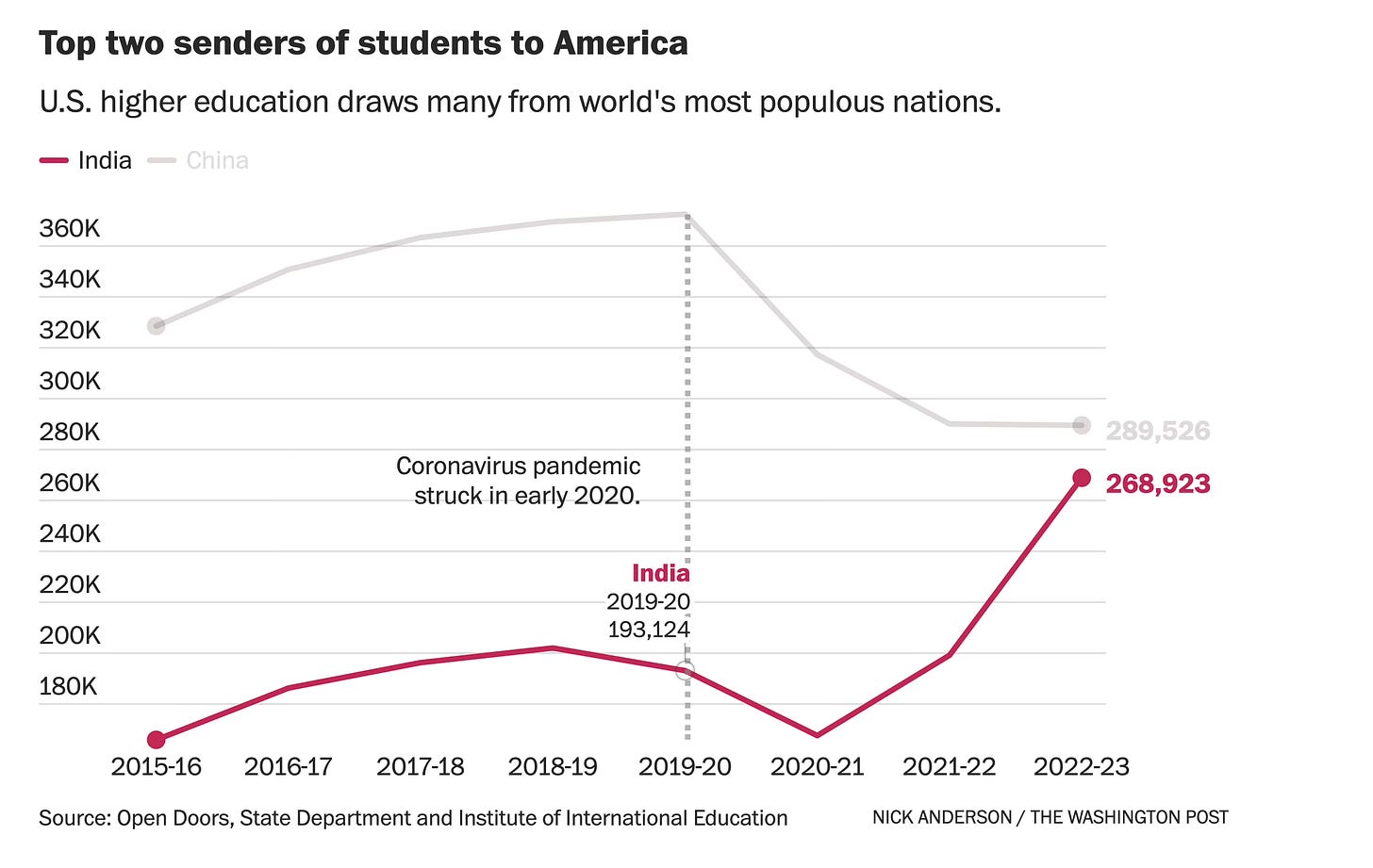

The total from India reached 268,923, up 35 percent, according to the Open Doors report from the State Department and the Institute of International Education. That set a record for what is now the world’s most populous nation.

Note that reference point: the late 1970s, because that is when East Asians (mostly Chinese) started showing up in numbers at certain US universities — particularly those with strong agriculture programs, like my U Wisconsin-Madison. I remember it well, because I was in high school (Boscobel Bulldogs!) back then and readying myself to head off to “Sin City” (my Dad’s favorite term for Madison) and enroll in the UW as my parents had, along with my preceding five siblings (my extended family has three dozen or so degrees from the UW, to include my wife’s three and half of my six kids with bachelor’s degrees).

So, there was never any choice for me: when one lives 70 miles from one of the finest public universities in the world and tuition back then was about $500 a semester — you simply go and figure out your career once there (mine was studying Russian for the never-ending Cold War — not a great prediction on my part).

Anyway, Madison was the “big town” for us, where we went for the most important shopping and where we saw the speciality doctors (plenty for me as a kid). It was modernity to me, as nothing excited me more than going there with one or both of my parents and glancing at the future — my future!

But back then, I noticed on all our drives through the campus that I was seeing — for the first time in my life — Asians (again, mostly Chinese). I remember it so because a big, early (for New Wave) hit song came out called “Turning Japanese” (1980, the Vapors from England). It was classic New Wave (frenetic, bit cheeky, guitar driven), and I loved it not only for the sound but for the implication of becoming something else. I had an older brother who studied Japanese and then went to grad school there, and, given his first-born status in the family, it felt like a harbinger of future developments (we were all going to become a bit Asian!).

Flash forward two years when I ask my now wife of 37 years out for a date and we go see “Blade Runner” with its future Los Angeles being a mishmash of Western and Asian cultures. Again, it all felt decisive and cool: we were living in an age of transformation, one in which civilizations collided and merged. Remember, this was back when going to a Chinese restaurant was a big cultural step for most people — long before any of that food became mainstream.

So, why the flood of East Asians back then? That was the time of early rising Asia, led by lead goose Japan. All of a sudden these rising economies were seeing wealth creation on a scale unknown to them, which enabled a lot of similarly rising families to send their kids off for the finest education that money could buy in America. In the case of China, it was the government itself sending all those ag and vet (veterinary) students to drive a radical transformation of that nation’s ag sector, a development that sent millions upon millions into the cities looking for work in factories over the subsequent years and decades (now all pretty much completed with the end of China’s follow-on demographic dividend triggered by that rural rate of procreation extending into the early urbanization period).

Again, for me coming to Madison at age 18 ready to save the world by studying Russian and figuring out those dastardly commies, I took great solace and pride in seeing all those Asian students wandering around the campus. It made me feel like our side was winning in this vague but powerful way — otherwise, why would they come?

Looking back on that period, I still spot the seeds of that Cold War victory. I realize that many Americans now feel like we screwed ourselves by encouraging and enabling Asia’s rise due to the competition they now constitute to our economy. But it was a key component of our Cold War victory that demonstrated to the Soviets that our mini version of globalization was winning while theirs was desperately falling behind.

Which brings us to today and this story.

Now it is East Asia’s turn to experience what we once did: watching globalization’s future unfold across South Asia while they rapidly age and have their economic prospects decidedly slow down to the level of a mature economic power (1-3% growth annual). It will be a humbling experience for the Chinese, and, as I have noted here many times, it will require China’s participation as the integrator of note in the global economy right now.

This is why the Chinese-Indian relationship is the most important superpower dyad in the 21st century (far more than EU/Russia, EU/China, Russia/China, Russia/India, India/EU, US-China, US-Russia, US-India, and US-EU): it will determine globalization’s integration of the last great pools of cheap labor (expressed as time-limited demographic dividends) in SW Asia and Africa. Break that development train (US enables Japan/Tigers, they enable China, China et al. enable SE Asia, which in turn enable India, and so on) and we all suffer the long-term consequences.

From America’s New Map:

As soon as rising India grasps globalization’s “baton” from risen China, New Delhi assumes the mantle as the economic development model of choice—a new consensus emphasizing political pluralism, cultural diversity, and an information technology/service-centric approach to cashing a demographic dividend. India is already moving down this path, as exemplified in its AatmaNirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-Reliant India Movement), clearly signaling its intent to achieve—on its own terms—its integration within globalization as an accepted superpower and champion of the Global South. As always, nothing is guaranteed, and New Delhi has recently revealed plenty of anti-democratic impulses, but the country starts in a good place and should remain there with the right kind of help and advice from powers that have trod that path before it.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Britain made a choice to accommodate—even mentor—America throughout its inevitable rise. That was a difficult call but one that proved to be Europe’s salvation across two world wars. America chose to do similarly with rising Japan and the Asian Tigers in the 1960s through the 1980s, in the process ultimately luring China down that stabilizing path with both America’s and Japan’s patient mentoring. Now it is up to China to extend some level of mentoring to rising India. It will be a difficult accommodation on both sides of this long-standing rivalry, but Washington must support its unfolding, however it complicates our own strategic relationship with New Delhi.

So yes, it is great to see the international crowd back stuffing US universities and it’s even better to see them being led now by South Asians and Indians in particular because it speaks to the power of that development dynamic and overall continuing dynamic strength of globalization: expressed not only in South Asia’s ongoing integration and rise right now but even more so by its pervasive digitalization.

I mean, check this chart out and tell me you can’t spot the passing of the developmental/globalization torch here from China to India!

You know, sometimes I feel like my job is helping people see the positives of this world when all the media feeds them is the negatives.

From the article as a summing up:

Other neighbors of India are showing huge growth. Nepal had more than 15,000 students at U.S. institutions in the past school year and Bangladesh more than 13,500. Both totals were up 28 percent. Pakistan had more than 10,100, up 16 percent.

The report shows a huge rebound of international higher education following the global public health crisis that struck in early 2020, disrupting flows of students to and from the United States and forcing most to take classes remotely. In the 2019-20 school year, the United States hosted about 1,075,000 international students. The number plummeted in the next school year, to about 914,000, before it began to recover.

And now, both the practical and supreme benefit accrued:

They bring crucial revenue to colleges and universities, often paying full tuition or close to it, and the federal government estimates they pump nearly $38 billion a year into the economy. They also provide enduring evidence of the global prestige of U.S. institutions devoted to teaching and research.

All good stuff that shows that America still makes the best stuff — including college grads.

“Made in the USA is something that these students and families want on their diplomas,” said Allan E. Goodman, chief executive of the Institute of International Education.

Here ends today’s optimism.