This is the second in a series of posts exploring my preference for broadly framing any issue/news story/trend/development in our world.

I tend to divide people between vertical thinkers and horizontal thinkers. Vertical thinkers are true experts in their specific field. They are drill-down artists of the highest order. They tend to know everything about something. When you really have a serious problem, they are the people you want responding … or, for example, operating on you!

Horizontal thinkers are generalists most interested about the intersections of various fields. They’re into pattern recognition and scenario projections. They appear less disciplined than vertical thinkers but they’re also highly creative. They tend to know something about everything. When you’re feeling lost and are not sure what is going on or what the problem might be, these are good people to consult.

There is no preferring one type over the other. Both modes of thinking are crucial in a complicated world, so smart decision makers tend to consult both types as circumstances indicate.

I, for example, spend most of my time with vertical thinkers versus horizontal ones. I also spend almost no time reading political science (my field) and instead read everything else. I want to avoid any of that “all things being equal” analysis because I never find all things are equal – much less unchanging. Again, if your thinking is all about boundaries and intersectionality, then you want to get to the other side of every “fence” demarcating your field versus others.

When it comes to broad framing an issue, you do want a horizontal thinker. Broad framing is taking the 30,000-foot view of things. That means looking at the dynamic over the very long run (how far does it stretch into the past, how much into the future) and across domains.

When I was in the Pentagon, I would tell briefing audiences that I wanted to avoid thinking about war in the context of war but rather think about war primarily in the context of everything else. My stuff was thus mostly about winning the peace – not the war. It may seem like a slim distinction, but it isn’t. Rather, it’s one type of wicked problem yielding to another.

In that VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) world of ours, this is the essence of grand strategic thinking: how something like climate change changes everything around it so … our response needs to embrace a whole-of-government/nation response (a simple definition of grand strategy: using all to shape all).

I am a big believer in the tell me how this ends school of thought popularized by General David Petraeus during the second Iraq intervention. That is solid broad framing on the temporal side. The harder stuff is integrating the everything else that comes with any history-bending dynamic – the follow-on effects and feedback loops and how fundamental rulesets tend to be dramatically revised.

A simple-but-powerful example from my book, America’s New Map: during the Global War on Terror, America established a clear superpower ruleset for targeting and dismantling “bad” regimes (our definition). Since then we’ve seen other great powers adapt that ruleset to their own purposes – most notably Putin’s Russia. America now seems stunned to find its own modeled behavior coming back at it in very undesirable ways. But these are the things that happen when you perturb a complex system like the “world order” you hear so much about these days.

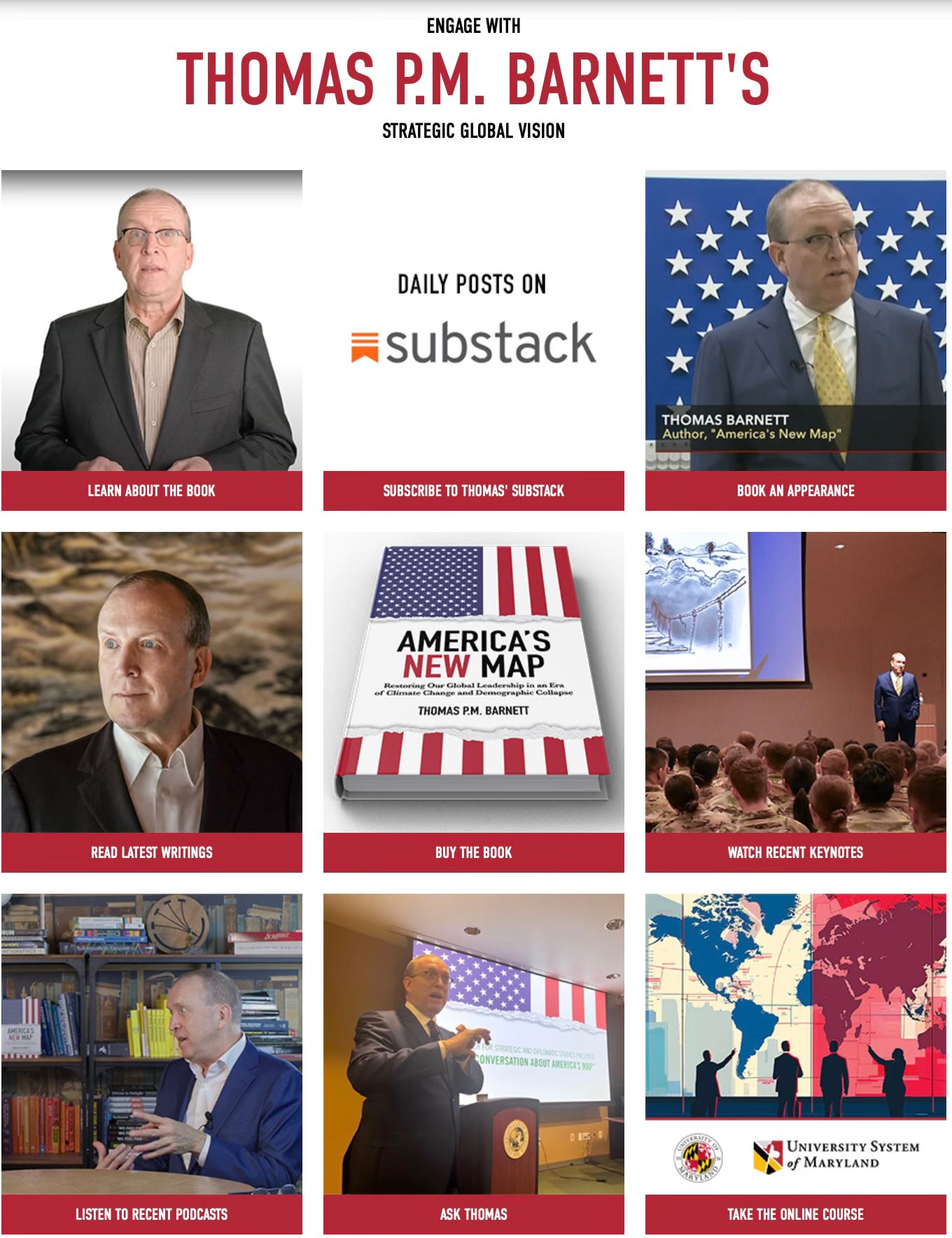

So that my basic take on what broad framing means to me. Over the next week or so, I’ll provide you six examples of how I do that on key global issues. It’s the kind of analysis Throughline and I are pursuing as a follow-on to America’s New Map – an effort we see as birthing more books and MOOCs (massive open online courses) and collaborative enterprise design and strategy engagements with our partners and clients.