Interesting El Pais article on how rapidly parts of Latin America are losing their arable land. As I noted in America’s New Map, we are witnessing a de facto transfer of wealth from lower latitudes to higher latitudes as climate change ruins lands in the former and opens them up for farming across the higher latitudes.

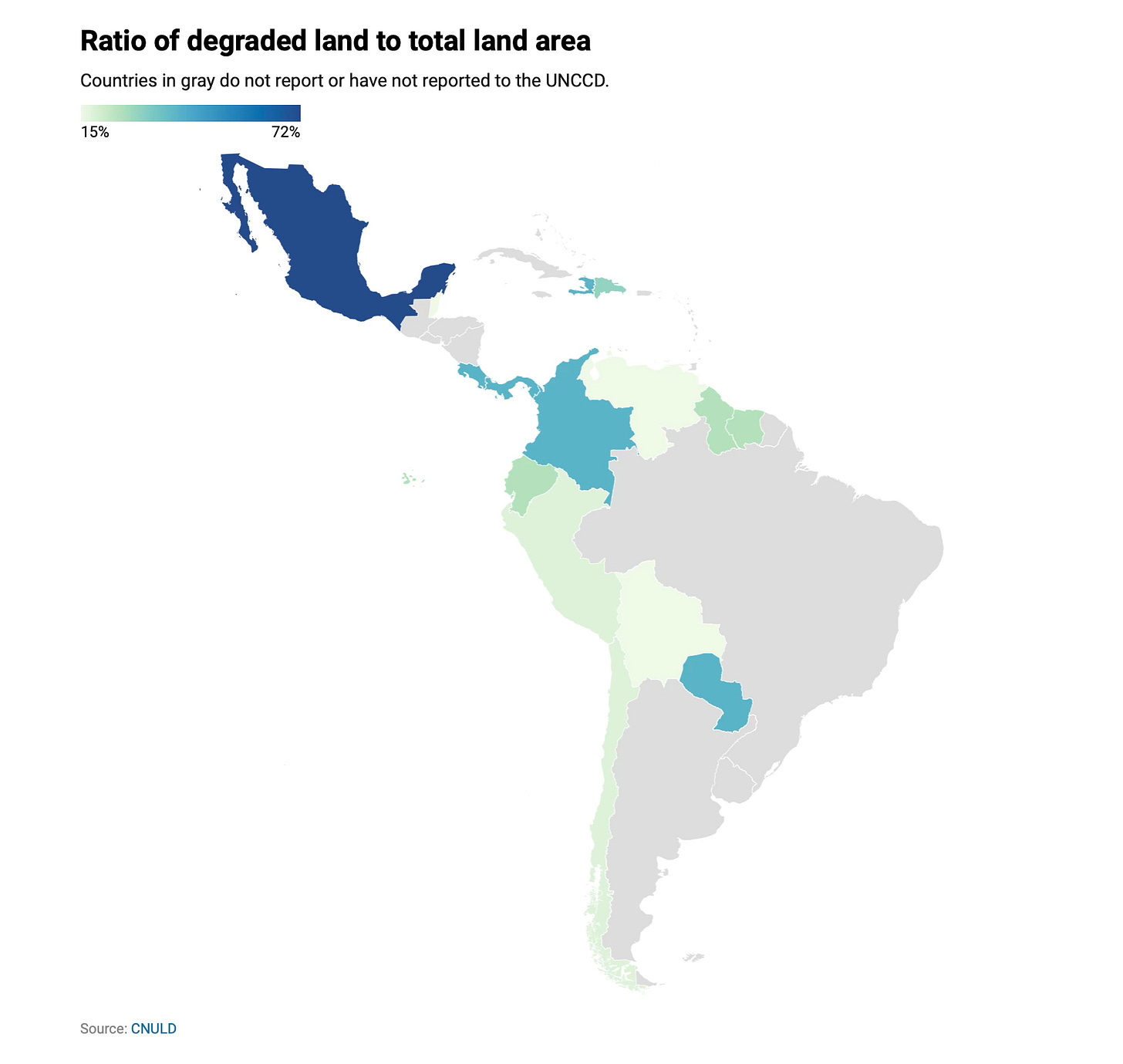

From the piece and based on data compiled by the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD):

Overall, in 2019 — and only taking into account the countries that report this type of information to the UNCCD — 378 million hectares were degraded in Latin America and the Caribbean, a proportion that is approximately equivalent to three times the size of Colombia [emphasis mine], which represents 22% of the region’s land. Meanwhile, drought affected 377 million hectares between 2016 and 2019 alone, with the most acute peak taking place in 2017.

Among the countries that have reported data to the UNCCD, Mexico is a particularly critical case. With 139 million hectares degraded by 2019, 72% of its surface area has already been affected by this phenomenon. Regarding drought, the UNCCD data panel indicates that up to 115 million hectares of Mexican land were affected between 2016 and 2019.

Trust me, the gray countries are not hiding good news.

This is the great irony/tragedy of climate change: it transfers land wealth from the poorer Middle Earth to the already rich “New North.” From my book:

No part of our world will be more transformed by climate change than the northern quarter of the planet, home to the vast circumpolar biome known as the taiga—a thick boreal forest resting on rapidly melting permafrost. Framed by the treeless tundra to the north and grasslands to the south, the taiga’s northward climate velocity—the rate and direction that climate shifts across Earth’s surface—is three kilometers per year. As this biome shift reveals arable land in its southern wake, it will render livable a band of Northern territory twice the size of Australia (14 million km2).

Gaining that 10 percent of the world’s landmass will offset a similar loss of livable territory along its middle quarter. Humanity swaps one environmental collapse (equatorial) for another (Arctic), accepting in compensation what geographer Laurence C. Smith dubs “the New North.”

Now, a lot of audience members and interviewers gasp when I put forth that notion of “two Australias” worth of land changing hands, but it seems less fantastic, does it not, when three Columbias’ worth of land suffers significant degradation in one year across Latin America and the Caribbean? I mean, that El Pais title is an eye-grabber with the title “Latin America loses 22% of its fertile land, the equivalent of three Colombias.”

The region is itself somewhat to blame for this devastation, as its rulesets (economic, social, political) do not work against this dangerous trend:

“We’re a continent that still has an extractive economy, that doesn’t recognize the value of nature and the ecosystem services it provides us, a region in which there are no economic or negative consequences for affecting the soil,” laments Costa Rican Andrea Meza, deputy executive secretary of the UNCCD.

And with the Chinese and the global economy as a whole growing that much more interested in extracting agricultural products from the Western Hemisphere, which only makes sense because we collectively enjoy about three times the percentage of the world’s freshwater supplies relative to our population percentage, the region is headed for a collision between the demands of the global majority middle class and the devastation wrought by climate change.

As I summarize in my book:

Globalization approaches a collision between an irresistible force (climate change) and an unmovable objective (lifestyle demands of a South-centric middle class).

It’s these sorts of indicators that drive me to downplay things like Ukraine, Gaza, and Taiwan as system breakers/shapers right now. Can they do damage to globalization? Sure. Will they change more than globalization evolves on its own? Unlikely. We in the West and particularly in America just tend to view China and other players as having that sort of power over the system when they don’t — nor do we anymore.

I mean, nobody issued a call, much less ruling, back in the 2000s for globalization to exponentially increase its digital goods traffic, expanding it by almost 50-fold in a decade and now constituting more than half its value. And that happened during a serious downturn-and-then-flatlining of the globalization’s goods-centric trade (along with FDI) — you know, the headlines that got everyone declaring the “end of globalization.”

Anyway, back to the story… because I really want you to pay attention to these estimates. First, about how much of the Earth’s surface is being affected:

The data from the region exceeds the global average, since the degradation reported by the 126 countries that shared their information reaches 1.5 billion hectares and is equivalent to 15% of the world’s surface area. If the necessary measures aren’t taken, it’s estimated that this land loss could increase by 4% every four years globally, affecting more than 1.8 billion people due to droughts alone.

In my book, I’m projecting only about a 10% loss of global arable land, mostly across Middle Earth, and a commensurate gain up north. If anything, I am low-balling it.

Then, about how many people are being affected.

In Latin America, there are currently around 539 million people (41% of the reported population in 18 countries) who have been impacted by land degradation. Regarding the drought — on which the UNCCD has information from 20 countries in the region — it’s estimated that 196 million people have been affected.

Here’s what I say in America’s New Map:

Development experts increasingly link state failure in the South to climate change, which reduces economic activity, forcing domestic factions to fight ever more fiercely over diminishing natural resources. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “ninety percent of refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, and 70 percent of people displaced within their home countries by conflict and violence, come from countries on the front lines of the climate emergency.” Today, we measure that distressed population in the tens of millions. Later this century, we will count them in the billions. Left to its own modest devices, much of the South will crater politically.

Latin America is about eight percent of the world’s total population. If just over 1/2 billion are being subject to serious land degradation (pushing them off the land, then into the cities, and ultimately northward) now across the region, then speaking of billions being put on the move is not hyperbole.

The article goes on to talk about how heat and drought act in concert to devastate lands. Here’s how I summarized that dynamic in my book:

Consider, for example, the challenge of far more severe and lengthier droughts highly concentrated along that Middle Earth band stretching 30 degrees north and south of the equator. Climate change speeds up the water cycle through faster evaporation and transpiration (evaporation via plants). That leaves less moisture for the soil, which makes it harder for plants to grow. Less plant coverage means greater ground absorption of solar radiation, raising surface temperatures, which helps generate more high-pressure weather systems (fewer clouds), which depresses rainfall and boosts solar absorption further, which leads us back to drier soil . . . in a cycle that grows more vicious with each passing year.

The article mentions some progress, however, in the Dominican Republic and pockets elsewhere:

With 1.49 million hectares degraded (31% of its surface area) and 4.65 million hectares that have been affected by drought (96%), the Dominican Republic could declare itself in crisis.

However, according to Meza, if we look at what was happening there in 2015, we would realize that the land degradation declined from 49% to 31%. The country began working on an ambitious soil recovery goal and, in fact, is working to restore 240,000 hectares in the Yaque del Norte river basin, as well as in cocoa production areas in the province of San Francisco de Macorís.

You have to believe that an “ambitious soil recovery” effort costs beaucoup bucks, the kind of money that requires a lot of local certainty to scale up.

Such certainty is not easily found across the region. For example, Argentina just electing a Trump-like figure promising to take a figurative chainsaw to the government. Meanwhile, the Southern Cone as a whole is undergoing a mega drought that reduces all such margins for error.

Again, my primary reason for exploring this piece is to validate the bold projections I offered in America’s New Map and to highlight just how real these devastating dynamics will be across our hemisphere, which we have to start viewing in an entirely different light, because we cannot thrive in North America as major portions of Latin America are being tanked by climate change.