Platform-centric naval warfare grows ever more obsolete

The many, the cheap, the unmanned, and the disposable beat the few, the absurdly expensive, the vulnerable, and the "unsinkable"

When I was a professor at the US Naval War College, I gave an address (okay, PPT brief) to the entire student body and faculty at the invitation of then President Rear Admiral Rod Rempt. As I was then a member of the Office of Force Transformation under VADM Art Cebrowski (then just retired) in Rumsfeld’s Office of the Secretary of Defense, I was a known associate, let’s say, of the network-centric crowd.

When I was asked by a student officer about the future of naval warfare (and warfare in general) at this talk, I gave the same answer I always gave in the form of a joke.

I’d say, “I’ve got good news and bad news: The good news is you will likely command dozens — perhaps hundreds or even thousands of naval vessels in your careers. The bad news is, almost none of them will have anybody on them.”

It was a toss-off line with no sense of timing or context, but it was a very accurate long-term projection nonetheless. As I watched the ginormous Gerald R. Ford carrier get built with every bell and whistle, with thousands of sailors as crew and a price tag well above $10 billion, it seemed stunningly apparent to me that the age of big, can’t-possibly-lose platforms was going away.

I mean, in my work, I was being exposed to the then-cutting edge of drones, and unmanned vehicles, and tiny steerable missiles not much bigger than a cigar — all of which we’re now seeing redefine the battlespace in Ukraine and not just on land but on sea.

So check out this great NYT story about How Ukraine, With No Warships, Is Thwarting Russia’s Navy, because now we’re seeing non-naval powers essentially deny sea control to naval powers — despite have no serious platforms of their own.

From the story:

In a small, hidden office in the port city of Odesa, the commander of the Ukrainian Navy keeps two trophies representing successes in the Black Sea.

One is the lid from the missile tube used in April 2022 to sink the flagship of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, the Moskva, a devastating blow that helped chase Russian warships from the Ukrainian coast. On the lid is a painting of a Ukrainian soldier raising his middle finger to the ship as it bursts into flames.

The other is a key used to arm a British-made Storm Shadow missile that slammed into the headquarters of the Russian fleet in Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula.

Impressive, huh?

Here’s the bottom line, twice presented:

Despite having no warships of its own, Ukraine has over the course of the war shifted the balance of power in the naval conflict. Its use of unmanned maritime drones and growing arsenal of long-range anti-ship missiles — along with critical surveillance provided by Western allies and targeted assaults by Ukraine’s Air Force and special operations forces — have allowed Ukraine to blunt the advantages of the vastly more powerful Russian Navy.

“At this point, the Russian Black Sea Fleet is primarily what naval strategists term ‘a fleet in being’: It represents a potential threat that needs to be vigilantly guarded against, but one that remains in check for now,” said Scott Savitz, a senior engineer at the RAND Corporation, a federally financed center that conducts research for the United States military. “Remarkably, Ukraine has achieved all this without a substantial fleet of its own.”

Despite being “vastly outgunned,” the Ukrainian naval forces have succeeded in breaking the Russian naval blockade of Odessa — the one piece Putin needs to complete his land locking of Ukraine. But that’s not all: the Ukrainians have taken the fight to Russia’s fleet:

About two dozen Russian ships and one submarine have been damaged or destroyed since Russia launched its full-scale invasion, Admiral Neizhpapa said. Oryx, a military analysis site that counts only losses that it has visually confirmed, has documented at least 16 damaged or destroyed ships.

And here’s the punchline from the Ukrainian VADM himself:

The war at sea has also demonstrated the impact of emerging technologies, transforming long-held theories about naval warfare in ways that are being studied around the world, perhaps nowhere more closely than in China and Taiwan.

“The classical approach that we studied at military maritime academies does not work now,” Admiral Neizhpapa said. “Therefore, we have to be as flexible as possible and change approaches to planning and implementing work as much as possible.”

For example, he said, it takes years to develop and build warships and more time to update them to meet new challenges. Yet maritime drones are evolving every month.

Right now in America we’re undergoing one of these periodic debates about how we need to build back up our fleet to match the Chinese ever-increasing volume of ships. There are all sorts of good, historical arguments for having more of anything than your opponent, but like is indicated by Ukraine, we are heading into a future where sea control is less the point, while the cheaper and more flexible capacity of sea control-denial is sufficient to thwart the ambitions of our fellow superpowers given to smash-and-land-grabs or the blockading of ports — to include China’s threat to Taiwan.

In other words, we should be learning here from the Ukrainians and not the Russians or Chinese.

We’re seeing the US Navy experiment with unmanned naval vessels with serious capabilities — the so-called “ghost fleet” (lovely name) being tested out right now. That, to me, is a realistic future force structure approach for an indebted nation now no longer with the capacity or ambition (or practical need) to try and manage every military crisis point around the world at all times.

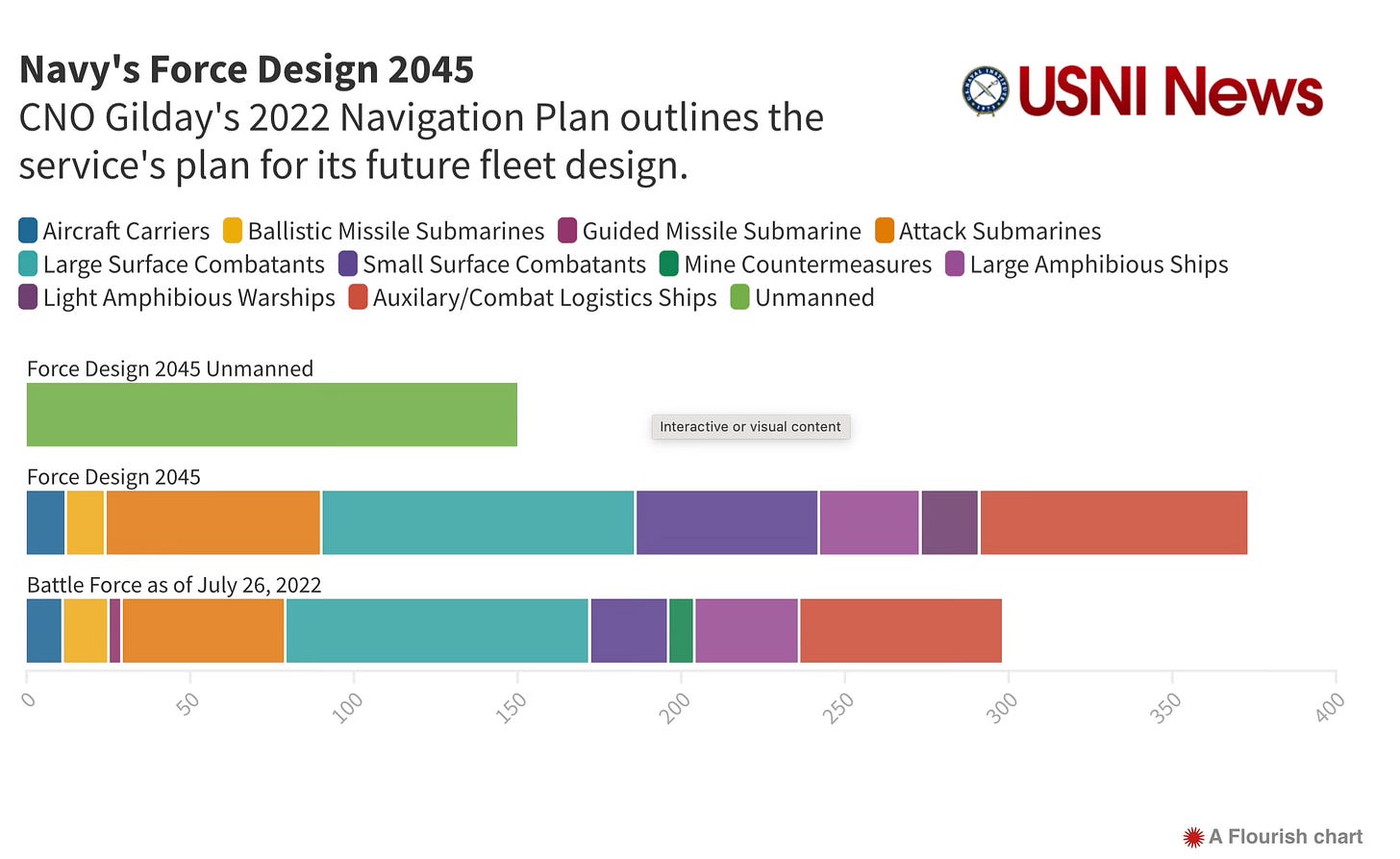

A shift to unmanned naval vessels (see the force structure plan for the year 2045 above), currently championed by the Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of Navy as a sensible way to bridge the gap between our perceived (i.e., self-imposed) global “requirements” and our budget, dovetails nicely with this emerging real-world battlespace. We can be the “arsenal of democracy” and satisfy ourselves with thwarting — in a very Reagan Doctrine manner — the strategic over-reaches of our competitors and enemies.

As I wrote in America’s New Map:

While it diminishes over time, the United States retains its role as external balancer in both the Center and Asia slices. But as we saw with Russia-v-Ukraine, our safest path forward in such conflicts is serving as an “arsenal for democracy”—Franklin Roosevelt’s pre-WWII policy that balanced America’s strong isolationism against Washington’s strategic instinct. Preemptively performing the same role with Taiwan vis-à-vis China, rendering the island nation an un-swallowable “porcupine,” seems another wise move by the Biden administration. We live now in a world of sufficient multipolarity where we can always find a worthy side to pick in any conflict without getting directly involved. In effect, this approach resurrects the 1980s Reagan Doctrine of bankrolling insurgent forces resisting a hostile superpower’s imperial strategies: it is relatively cheap and often effective.

I have often written about the difference between “market making” activities and “market playing” activities. When we built the current world order, we started off, after WWII, in very market-making mode, sometimes getting so lost in that role that we overestimated the importance of what can now be viewed as largely irrelevant conflicts (like our participation in Vietnam) that changed nothing — despite our market-making obsession with concepts like the “domino theory.”

The big shift represented by Obama and Trump and now Biden is one from market-making activities to a more selfish, realistic, and constrained market-playing approach. That shift requires us to be far more sensible with our resources, commitments, choices, and engagements in the realm of national security. Moving our military force structure toward that network-centric ideal (many, cheap, unmanned, disposable) is a big component of that strategic adjustment to the multipolar world we long sought and now inhabit — uncomfortably.