Positive externalities caused by US-style globalization: democratizing trade & longer life-expectancy

Spreading trade spreads access to medical advances and they revolutionize life-expectancy at birth

People ask, how do you research a book like America’s New Map?

The answer is I spend a lot of time curating my list of trusted, productive sources. I literally sometimes sit on an image or a chart or a fact for years until I find the right moment to use it.

Along that logic, let me state for the record that I consider “Our World in Data” to be one of the great resources on the web for someone like myself who wants to figure things out. I’ll cite others in the months ahead, but there is no site that I used more in developing America’s New Map than Our World in Data. Great charts, great databases to peruse, and great analysis in the accompanying articles.

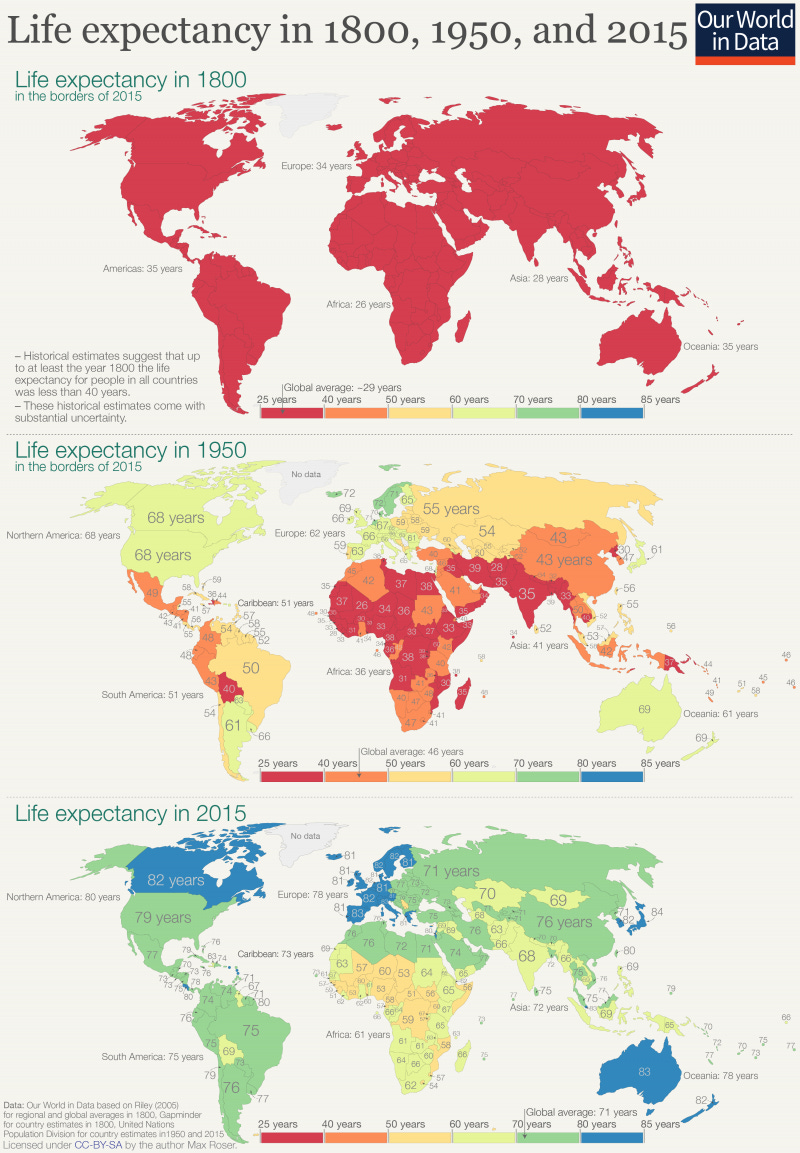

Here is the site’s summary chart sequence for life expectancy, my only disappointment being no visual for 1900, because that’s how I couch the advance in the book:

Humanity’s lengthening life span is both entirely unnatural and our most complete victory yet over our environment. In 1900, global life expectancy at birth stood at the same level (low thirties) it had maintained since the Roman Empire. Despite the twentieth century’s conflicts, human life expectancy doubled to seventy years by the year 2000. That stun- ning achievement was overwhelmingly enabled by the pervasive use of vaccines in early childhood. Talk about a buried headline. (p107)

An amazing story of human progress captured in just a trio (or so) of family generations. My grandfather J.E. (1895) was born in a world where global life expectancy at birth hadn’t really changed much compared to … forever.

Two generations later, I’m born in 1962 and life expectancy has jumped incredibly for all sorts of reasons (vaccines, antibiotics) that kept me alive through a very precarious 0-5 years old period. If I’m born 40 years earlier, I never make it to kindergarten. Instead, I make it with ease, processing all sorts of disease and infections.

By the end of this storyline (2010-ish), my wife and I are welcoming two little twisted sisters from Ethiopia who were well on their way to not making it to age five — until they emigrated to the US, were comprehensively de-wormed of more parasites than I care to remember, and then grew six inches in six months thanks to an improved diet that they no longer had to share with those intestinal worms, shooting up from the 15th percentile for their age to something more like the 75th percentile.

What I like most about the chart sequence is that it shows what a difference it made to have America in charge of the world system following WWII: adding 25 years of life expectancy across a mere 65 years of time versus only 17 years over the previous 150 (and with virtually all that early growth really accounted for just in the advanced West).

In sum, the US-style of globalization (based on trade versus colonial trafficking of goods) truly democratized and globalized the factors that lead to longer life expectancy.

In the book, I note the baseline benefits of trade:

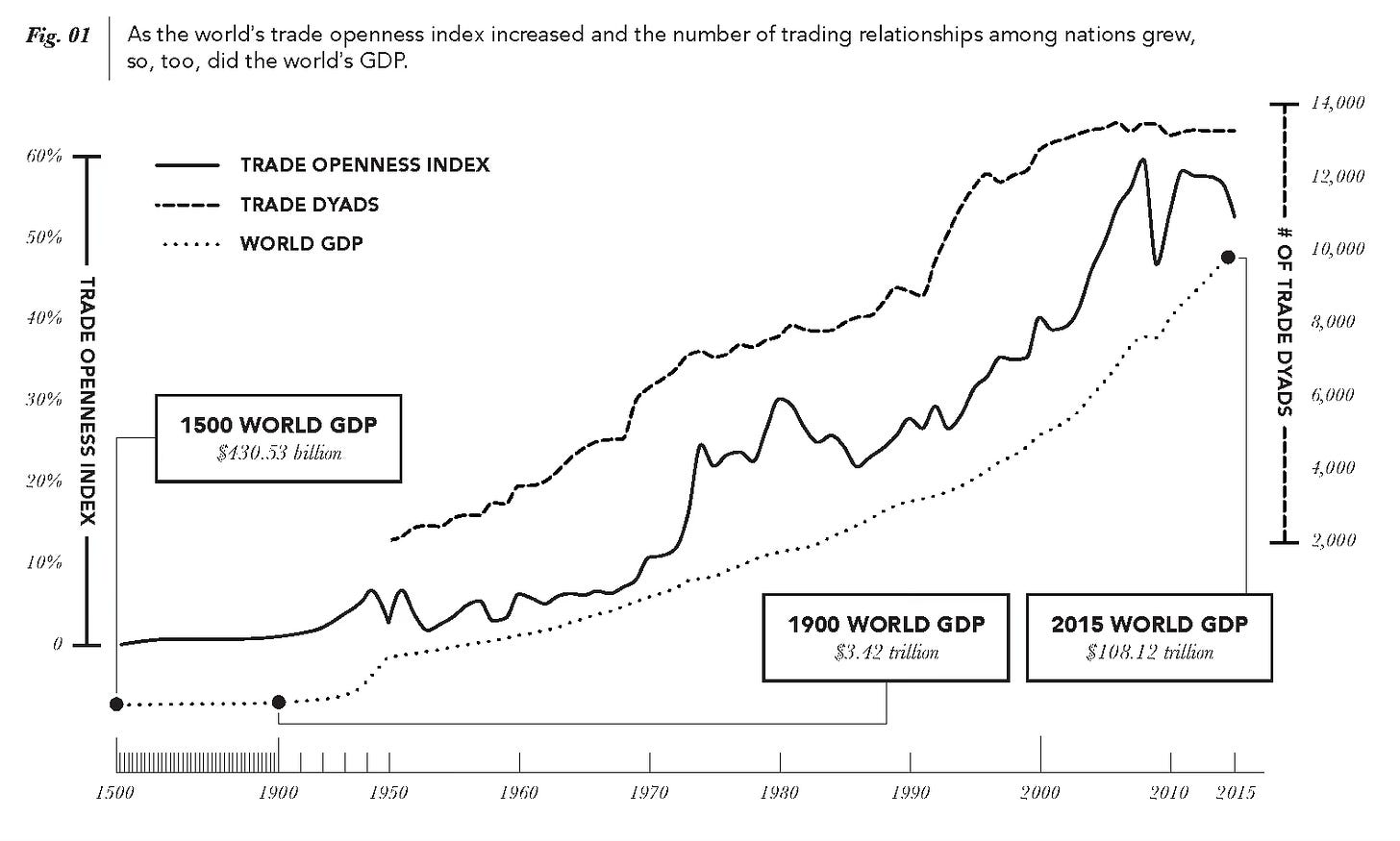

Abundant historical data proves that the more your nation trades, the faster your economy grows due to heightened competition, economies of scale, and more exposure to, and adaptation of, advanced technologies created elsewhere.

The Our World in Data chart that inspired that graf:

The most important technology that your country gains access to? That would be medicine and medical care. But you can’t get it if you don’t trade. Check out the nature of human health in North Korea, where the average person is pounds lighter and IQ points lower and inches shorter than their twin counterparts in South Korea.

To wrap this up, I need to go to my favorite data presentation from Our World in Data: one measuring the pervasiveness in trade. Here’s how I put it in the book:

When we add up all possible state-on-state combinations (dyads) in the world in 1950, four-fifths of them featured no direct trade. Today, three-quarters of all dyads feature direct trade of some sort. That is a revolution in human affairs made possible by US-style globalization.

Key to that revolution is the expansion of trade outside of advanced capitalist economies. Trade among rich countries accounted for two-thirds of the global total in 1945, the rest involving less-developed countries. Today those proportions are reversed, meaning US-led trade liberalization efforts democratized global economic connectivity—another hugely positive legacy.

Here’s the charts I sourced at Our World in Data:

Putting all that sort of data is how Juraj Mihalik and Tom Zorc built the data visualization that we included at the end of that thread (Thread 1 - The Empty Throne: Globalization Comes with Rules But No Ruler).

I particularly liked Jim Nuttle’s interpretation of that thread in the below illustration:

The rules are everything, but they’re constantly up for re-definition.

This is the nature of globalization today.