[POST] Conjoined at birth, separated by death?

Was America's superpower status inextricably linked to the rise-and-fall of the Boomer Generation?

This is a reader-supported publication. I give it all away for free but could really use your support if you want me to keep doing this.

Whether or not America's rise and potential decline as a superpower is inseparable from the trajectory of the Baby Boomer generation is a subject of ongoing debate. There’s no doubt that the Boomer generation's size, timing, and influence have shaped America’s global trajectory. But, to me, the real question is, did the Boomers waste the efforts and legacy of the Greatest Generation and essentially “spend that trust fund” over the decades, right down to destroying almost everything that generation built as the Boomers now finally exit the political realm — with Trump as the ultimate destroyer and the last of his disastrous breed?

The Greatest Generation, by waging and winning the fights against fascism and communism, set the Boomers up in unparalleled wealth and global power in the 1950s, and then pushed through Civil Rights while the earliest Boomers were starting college.

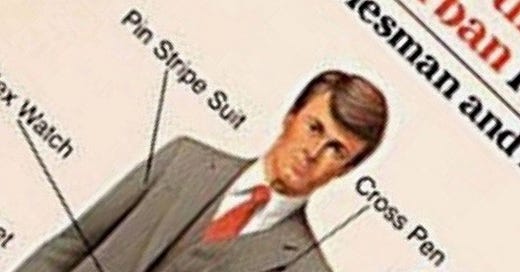

In my reading, the Greatest Generation’s influence peaked around 1965 and began its slow surrender to the whims and desires of the Boomers from that point on. So, yeah, while we can say that the Boomers came of age during a period of immense social change, driving movements such as civil rights, anti-war protests, and shifts in cultural norms (e.g., feminism, environmentalism), they didn’t really dominate the workforce and political elite until the early 1980s (the shift from Hippies to so-called Yuppies).

Again, the Boomers were blessed from the start, growing up in a time of American confidence and expansion. Like most would-be “revolutionary” generations, after the raucous efforts of their youth, the real talent went into business and technology and the leftovers went into politics. As such, the Boomers remade our world with the information revolution but passed very little meaningful legislation, instead succumbing to a bizarrely counter-productive ideological polarization as they aged.

The Boomers accumulated vast wealth, but also presided over growing income inequality. Their consolidation of political power and economic resources created serious barriers for younger generations, and has contributed to a serious decline in our nation’s institutions — almost all of which now are held in low esteem as the Boomers begin to depart.

The Boomers’ long reign likewise distorted America’s perceptions and understanding of the Greatest Generation’s greatest legacy — namely, the international liberal trade order we now call globalization.

From America’s New Map:

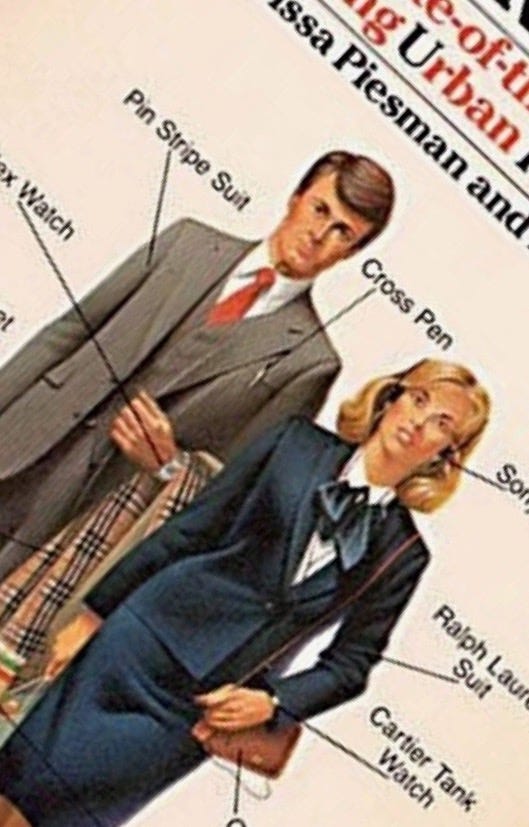

US consumption has long shaped global consumption. That economic self-centeredness makes it hard for Americans to understand globalization’s liberating and disorienting impact.

Outside of the radical Islamist response, most Americans remain unaware of how the spread of US-style globalization around the world challenges traditional societies. Globalization’s state-integrating dynamics so mirror our American Union’s long-standing practices for meshing our member states that we struggle to view them as anything but entirely normal. However, the basic freedoms that fuel US economic activity remain challenging concepts across much of the world.

Take unrestricted movement …

There is also a generational factor that makes it unusually difficult for Americans to recognize, much less own up to, the profound impact that our brand of globalization has had around the world. Starting with our Boomer generation (1945–1964), America served as the undisputed center of global demand. For decades, that meant the global economy revolved more around our tastes and desires than those of any other region. While Americans constitute 5 percent of the world’s population, our share of global consumption has long been a multiple of that (four to five times). It is not just that Boomers have long dominated the US market; by extension, they have long exerted outsized influence throughout the global economy.

So yes, when the preeminent power of your consumer demand, along with your rule-setting role, places you at the calm eye of the globalization storm, you really do have a tough time comprehending the transformational power you have unleashed along its vast front. You may even be completely oblivious to it.

That is . . . until the terrorist strikes of 9/11 remind you that there are bad actors who will wage unspeakable war to prevent your ways from overwhelming their own. Or 2008 reveals Wall Street’s latest risky debt instrument just collapsed the US housing market, in turn imploding global financial centers and markedly slowing growth among emerging economies whose most vulnerable populations then feel forced to emigrate. Then it gets easier to recognize and comprehend.

But what really makes that influence clear is when you discover you no longer possess it, which is what has happened over the last couple of decades, thanks to China’s stunning rise. Remember when, in the 1990s, cable business network analysts were always saying that as long as US consumer spending remained strong, the global economy would be fine? Nobody says that anymore. Now, economists speak of Chinese consumers with such reverence. A good example: Hollywood self-censoring its films to avoid offending China’s vast audience.

That is a big part of explaining America’s recent loss of self-confidence, along with growing fears of globalization itself. The future just does not look like us anymore. That can be particularly unnerving for older Americans who, looking around their country today, no longer see “the America I grew up in.”

The good news? Our younger generations (Millennial, 1981–95; Gen Z, 1996–2010; and Gen Alpha, 2011–25) have already experienced our shared demographic future, growing up in an America that far more approximates the world’s diversity. As such, their concerns for the future are eminently more practical, while their deepest fears center on climate change—as they should.

The bad news? The Boomers are still largely in charge of our political system (we have yet to elect a post-Boomer president) and seem stubbornly reluctant to cede authority to succeeding generations.

Why that matters: Boomers, those inveterate weaponizers of nostalgia, are inherently attracted to the notion of resurrecting America’s golden age—namely, their childhood and youth. Cold War Boomers also have a tough time detaching themselves from that era’s enemy archetypes—Russia and China. While we clearly face genuine threats from each power, the Boomers’ tendency to view both competitions in entirely existential terms only pushes Beijing and Moscow into confrontational stances with America and—worse—each other’s arms.

This is especially unhelpful as China steps into its role as globalization’s demand center in so many domains. Just as we Americans had a hard time owning up to the global footprint of our inordinate consumption, so now the Chinese struggle with such responsibility, seeing themselves, after their “century of humiliation” at the hands of colonial powers, as a perpetual underdog at worst and an avenging superpower at best. To the extent that America’s political leadership continues defaulting to cold-school demonization of communist China, we can expect Beijing’s stability-obsessed leadership to avoid global responsibilities they might otherwise embrace. While Washington hard-liners would welcome that outcome, it would be to the world’s detriment. America’s global leadership is no longer feasibly unilateral in execution.

So, no surprise: as Boomers age and retire, America faces new challenges: demographic shifts, political realignment, and questions about sustaining its global leadership. As such, history is likely to view the rise and fall of the Boomer generation and America's superpower era as closely linked, if not inextricable, reflecting the inescapable interplay between demographics and national destiny. I mean, if we can push similar arguments about China’s looming demographic collapse, then it’s no stretch to suspect that America’s superpower status was inevitably slated for post-Boomer decline.

Good or bad thing?

I guess I would say it all depends on the transition. Biden segueing to Harris would have been one path, but Biden being dismantled by Trump is a completely different one — indeed, a weird retreat into the past.

Future generations are thus likely to see the Baby Boomers as a generation that plundered the Greatest Generation’s legacy while building none of their own — outside of the information/computing revolution. When it’s come down to social, economic, and political challenges, the Boomers simply have not provided much leadership, instead preferring to endlessly re-litigate the issues of their youth. The abortion issue is the perfect example.

Trump is the perfect Boomer, prioritizing short-term gains over long-term sustainability. What his “revolution” delivers is the same old GOP tax cuts, wild deficit spending, and continued inaction on climate change and infrastructure, leaving those “details” to future generations who naturally already despise the Boomers.

The Boomers have held onto power as a sort of Generation-For-Life within our political system, creating the same policy constipation that bedevils China under Xi Jinping. They have persistently resisted institutional changes sought by more diverse and progressive younger generations and now actively wage culture wars on them (e.g., the demonization of DEI).

This "Boomer ballast” has slowed societal adaptation just as technological and demographic and climate developments are being turbo-charged. In response, Millennials and Gen Zs are — quite naturally — far less likely than Boomers to view the US as exceptional or to support an active global leadership role.

Over time, historians will view the Boomers as the architects of both America's greatest technological successes and some of its most persistent political problems. Their generational rule will be judged as a a period of unprecedented-but-wasted opportunity — one in which critical long-term challenges were disastrously deferred.

Again, Trump is the quintessential Götterdämmerung to the whole Boomer reign — its self-negating conclusion, its inevitable tragedy, and its superpower suicide.

We can blame it all on the Chinese and their various “shocks,” but these wounds are entirely self-inflicted.

Again, from America’s New Map:

Citizens most readily take ownership of a country they have had a hand in creating. Like a trust-fund generation, the Boomers cannibalized that which was bequeathed to them by the Greatest Generation. Gen Xers to date offer few reasons for optimism, content as too many of them seem in extending and exacerbating their predecessors’ self-destructive culture wars.

No, if the American Union is going to thrive again, it will be through encouraging, empowering, and unleashing Millennials, Gen Zs, and Gen Alphas to redefine what it means to be American and what America means to become. As true globalization natives, these generations, per Abraham Lincoln, “shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

As a tail-end Boomer/Generation Jones type myself, I welcome the criticism of upcoming generations, because it shows they still care.

After all this generational self-criticism, let me leave you on a positive note:

Every US generation, right through the Greatest Generation, has left America better and bigger than they found it. The Boomers are the first generation to lose that throughline—to our great shame. That disastrous development needs reversing, and globalization’s regional consolidation, accelerated by climate change’s remapping of our world, is a made-to-order opportunity.

China will never win our world’s allegiance on generational terms. The government there simply mistrusts its own people too much for that to happen. Furthermore, Beijing’s demographic deal with the devil won’t afford it enough time to lead by example and produce lasting rules in its wake.

America, furthest along in this global experiment in integration, remains this Shakespearian tragedy’s Hamlet.

That dreaded potential outcome is why I wrote the book. Just because the Boomers wasted their chance doesn’t mean subsequent generations must follow their weak leadership with more of the same.