This is a reader-supported publication. I give it all away for free but could really use your support if you want me to keep doing this.

I am a neurotic from a long line of neurotics, which is to say there’s a lot of Irish in my family lineage. The Irish tend to spot a dark cloud in an otherwise sunny sky — that assumption of impending doom. Even amidst success, the predominant vibe is now there is no where to go but down.

I’m not complaining. That mentality has made me a rather inventive scenario-planner across my career. In other words, I have taken a form of mental illness and monetized it.

We should all be so lucky.

This pessimistic streak among the Irish stems from that island’s long and difficult history, marked by invasions, famine, colonization, and political violence. Most Irish admit to a certain existential gloom, shaped by those centuries of hardship and a sense — common to most peoples — that their struggles are unique and enduring.

I came by my version of this Irishness thanks to my very Catholic and very Irish mother, who schooled me throughout my childhood about what the Irish had suffered and why we should always feel a bit guilty about watching Masterpiece Theater on PBS.

Good example: I see that Bono is spreading the word that we’re closer to a world war now than at any point in his lifetime. I think that’s complete nonsense and just bad analysis, but I get the negative vibe. There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty in the system right now, and while it’s tradition to focus on the uncertain paths of states (WTF’s going on in America right now? Will China rule the world? Will Europe fall apart? etc.) or — worse — the uncertain path of our world order long directed by an America now fleeing that task at speed, I feel like the uncertainty of today is far more individualized. We may express it in terms of unhappiness with the direction (or “right track”) of our country (because that’s the question favored by pollsters), but, to me, the building angst in the system is concentrated at the individual level and not the state or system levels.

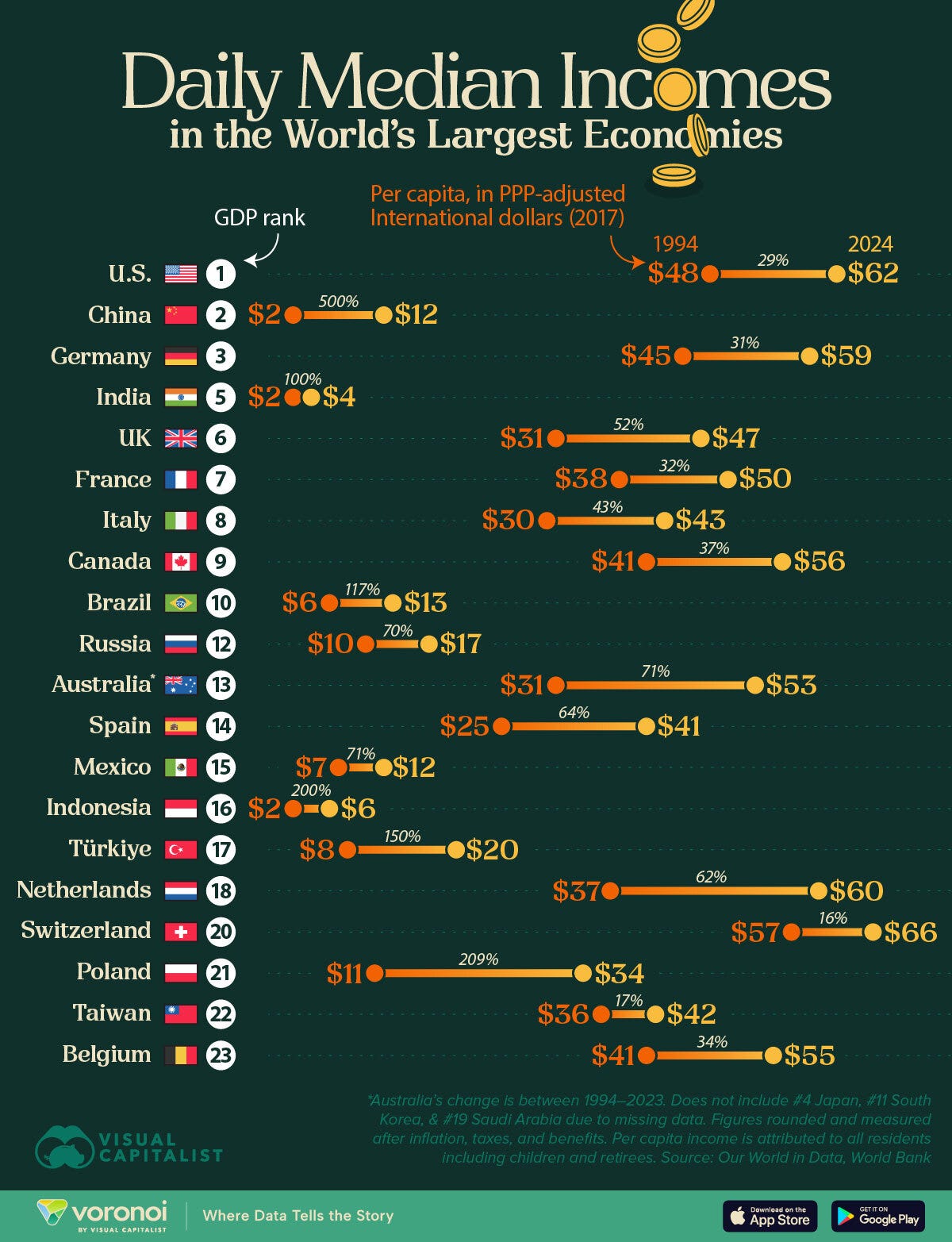

The core issue today is not simply wealth inequality (which we can argue about), but rather the widespread uncertainty and pervasive fear of downward mobility that now defines the American experience and much of the world’s experience. Hell hath no fury like a newly-minted middle class person facing a drop back into historical poverty [I’m pretty sure I wrote that in one of my books.]

When America was “great” was when you could go directly from high school to lifetime employment in manufacturing, complete with old-age pension — you know, back when an auto worker seemingly defined that good life (I not only build them but I can afford them and all the mobility that comes with them!).

That good life, then, came with healthcare and a pension system — two benefits now systematically denied to many Americans, meaning most of us head into retirement and old age with dread over the inevitability of progressively losing our purchasing power as we lose our physical and mental skills, setting us up for a life denouement consisting of ever worsening —and isolating — care while what’s left of any personal wealth is drained by the system, meaning most of us zero-out in the end and can’t really offer our offspring much of a generational wealth transfer (denying us even that sense of legacy).

That’s the ugly truth of America today: way too many of us die alone and impoverished.

Having been married to a social worker specializing in elder affairs and end-of-life issues for almost four decades has skewed my perspective some, I will admit, but only in the sense that I am acutely aware of how most Americans are treated on their way out the door and it is brutal — grotesquely humiliating even.

So, when I look ahead to an aging/aged America, and I factor in the reckless nature of government spending — particularly among the Republicans who want everything cut while they’re out of power and then vote for massive deficits whenever they’re in power …

… it’s enough to make you lose faith in America’s future.

Hell, toss in the mania among the rich for bunkers and doomsday shelter and I don’t know how the average person handles it today — that sense that we’re screwed no matter what.

I mean, it’s one thing to watch zombie apocalypse movies and say, Wow! Imagine living through such a scary scenario, and quite another to realize that you’re far more likely to be one of the zombies than those heroic types holding them off.

As I have argued here before, it’s clear that, while America has excelled in capturing the benefits of globalization and technological advancement, most Americans have not shared sufficiently in those gains. Instead, many face stagnating or declining real wages, eroding job security, and a generational decline in the likelihood that children will surpass their parents’ economic status — all of which is BRUTAL to one’s spirit.

And, as for the “great wealth transfer” I keep reading about, the truth is that’s a dynamic overwhelmingly limited to the wealthiest, while the majority of Americans see their long-term prospects dimmed by high healthcare costs, Trump-decimated social safety nets, and — compared to Europe — a profound lack of retraining opportunities for workers facing job elimination at the hands of automation and robotics and AI.

This very Irish sense of doom-and-gloom is compounded by political and social immobility: people who want to move for better opportunities often feel stuck to their homes, their jobs, the healthcare their employers provide, and/or family obligations. Those who feel trapped gravitate toward zero-sum worldviews and political movements that promise to halt or reverse this brutal change — rather than adapt to it, which only increases the everything-is-broken vibe.

In sum, the real crisis is not just about the distribution of wealth, but about the erosion of the American promise of upward mobility and the resulting fear that the future holds more risk than opportunity.

I feel it in my gut every day: Take away my health and/or remove me from the picture and my family would immediately face a great deal of economic pressure. Income-wise, I have been the great backstop: paying for college, erasing student debt when incurred, providing that first car, augmenting rent when necessary, paying off unexpected medical bills.

I and my spouse are the bank, just like my parents were for their kids.

I am happy to do all these things but they come at certain costs: my spouse is working a brutal schedule in her mid-60s because we need the healthcare her employer provides. If I were to try to make that happen on my own as a consultant working 1099s across the board, it would cost me somewhere in the vicinity of $50-60k pre-tax to cover myself and my spouse and four still dependents.

I will tell you: I know full well why people are having fewer kids. It’s because they’re incredibly expensive. If my wife and I had stopped at 1.8 kids (America’s fertility rate today), we’d be swimming in income and snatching up wealth at a high rate at this point. We could also vote Republican and constantly complain about immigrants ruining America.

But we chose differently. I’m the eighth of nine kids in my birth family: it’s how I was raised to view the world (all kids grow up thinking the world is just like their family — for good or ill) and so we kept adding kids (adopted from overseas) until it just became financially impossible.

I could look back on those choices and say, you get what you deserve with those decisions, but none of those decisions were accidental. Instead, they were all based on faith in the future, which I can still muster even as I feel the odds increasingly turning against me as I age.

I am one or two phone-calls away from financial free-fall. I’m also one or two phone-calls away from financial security. It would have been nice to have this all settled well before 63 (my age as of next week), but the same thing happened to my dad, so there is some symmetry there, from which I take some comfort even as I must recognize how my health holding up is a huge component of my family’s doing-well financially and that, that too is always just a phone-call or two away from disappearing (hell, maybe just one or two falls away from disappearing).

Why share this angst?

First off, it’s cheaper than therapy and might actually make me some money!

Second, it just feels so right below the surface right now, and I know what it feels like to get that call and have your income suddenly collapsed to a fraction of what it was just yesterday. I also have learned that the difference between being a W-2 and a 1099 ain’t really much of a difference in this economy — except for that all-important healthcare.

I’m also seemingly stuck with a house I suddenly can’t sell because President Chaos is having too much fun generating vast uncertainty throughout the US and global economy, and that pisses me off big-time, while making me feel vulnerable and powerless.

I also come across media article upon article about how Gen X feels totally screwed, while Millennials fear for their employment future, and why Gen Z just plain feels lost and susceptible to doom-spending every chance they get. None of that feels right or healthy in an economy and political system in which the rich are becoming grotesquely more wealthy per unearned or passive means, meaning all they have to do is keep living the good life and they are certain to grow wealthier and more secure in their life paths — all the while nurturing their own fears that a doomsday is coming when the rest of us “zombies” will come for them.

Since the 1980s, regressive tax changes have empowered the wealthy to keep more of their money and pass more of it on to their sons and daughters. In advanced economies, the amount of inherited wealth has more or less doubled as a proportion of GDP, compared with the middle of the last century.

Yes, experts can and should counter with the analysis that says being a middle-class person today in the West is to command resources and opportunities and information that even the world’s richest couldn’t command a century ago. But that sort of big-picture salve just doesn’t do much for the average person who knows full well that they are one health crisis away from permanent poverty — that scenario staring them in the face every day while a “billionaire boom” unfolds across virtually all of the advanced economies.

As one expert recently put it:

We recognize extreme poverty as ruinous, but this turbo-charged affluence is deeply damaging too.

Duh!

His argument: we recognize a line of extreme poverty and mobilize the state to combat that, so why not do the same with extreme wealth?

Makes sense, does it not?

America is wealthy: $160T wealthy. If everyone in America had the same amount of money, the average person would be worth a half-million-dollars, and I would feel totally justified in making a family of 8 happen.

Practical? No, but the right direction and ambition if you want to avoid political violence and revolution.

America has done well with globalization. We just refuse to spread that wealth around, yielding the angry populism ruining our politics today — in addition to the cynical rule by billionaires.

It needs to stop, as I am not seeing Trump’s policies making things better but actually exacerbating them in unsustainable ways.

So, I am left with the same prayer I’ve been offering for years now: please God let us move past the Boomers as political leaders as soon as possible. They have been an unmitigated disaster and cannot leave the political stage fast enough.