Racking and stacking inconceivables

A grand strategy version of "Would You Rather ...?" on dollarization

First off: Welcome to any and all new subscribers from Virginia Tech and its Corps of Cadets! This is a free post to give you a sense of what I write here.

As the book promotion has unfolded, I and mine increasingly link up with established players in various domains who are interested and eager to work the North-South integration angle — whatever the medium.

In many ways, there is nothing new under the sun when it comes to this broad topic: we know how it was done in the past and we have witnessed how Europe has pursued this eastward over the past several decades (still ongoing). In sum, there are plenty of paths to explore, including many that have been broached time and again over the decades, like the question of Latin American states dollarizing their economies, which, in a sense, locks them into a de facto currency union with the US, meaning we get to make the big decisions on the dollar but still have to endure outcomes beyond our border that nonetheless reverberate back on us to the extent that we sense some loss of control.

On these big transitions from “inevitables” to “inconceivables” (a solution that seems impossible to pursue now but will eventually become the obvious answer), it all comes down to a sort of Would you rather …? calculation (WYR?), which is best thought of as a rolling calculation — meaning a constant recalculation over time. Most of what I describe as inevitable in North-South integration does not meet this test at this time, as denial, inaction, counter-action, and incrementalism all strike policy makers as better paths.

This situation mirrors the whole climate change debate/response world.

But my strategic bet is that climate change will change all the relevant variables enough to eventually tip those WYR? calculations from “the way things have always been” to “the way things have to be now.”

No, it won’t happen under the Boomers or Xers: those dogs are too old.

But it will happen under the Millennials and Zs — not because it’s cool or visionary but because the alternative of doing nothing will simply hurt too much.

Think of it like the incredibly uncomfortable elective surgery that you put off for years (No way!) until … you just can’t stand it anymore and you’ll submit to whatever to make the pain go away.

Some people think we’re at that point with immigration now — and those people are kidding themselves to think a wall is going to do it.

No, we’re going to need a bigger boat — a lot bigger.

Clearly, the US would rather have all of Latin America operate on their own with stable currencies, because when crazy inflation kicks in, as it has in the past, bad geo-political outcomes ensue. Why get involved? Unless, of course, that scary situation triggers mass migration to your shores (see Venezuela for several years now).

That perfect world has never existed and won’t come about anytime soon. Instead, the smart bet is that climate change will wreak economic havoc throughout Latin America on a scale that’s hard to contemplate now, given our mixed feelings on immigration and other “scary monsters” out there that dominate our news feeds.

Still, LATAM states that have been put through such wringers in the past often toy with the idea of dollarizing their economies, and some already have (one, Panama, more than a century ago).

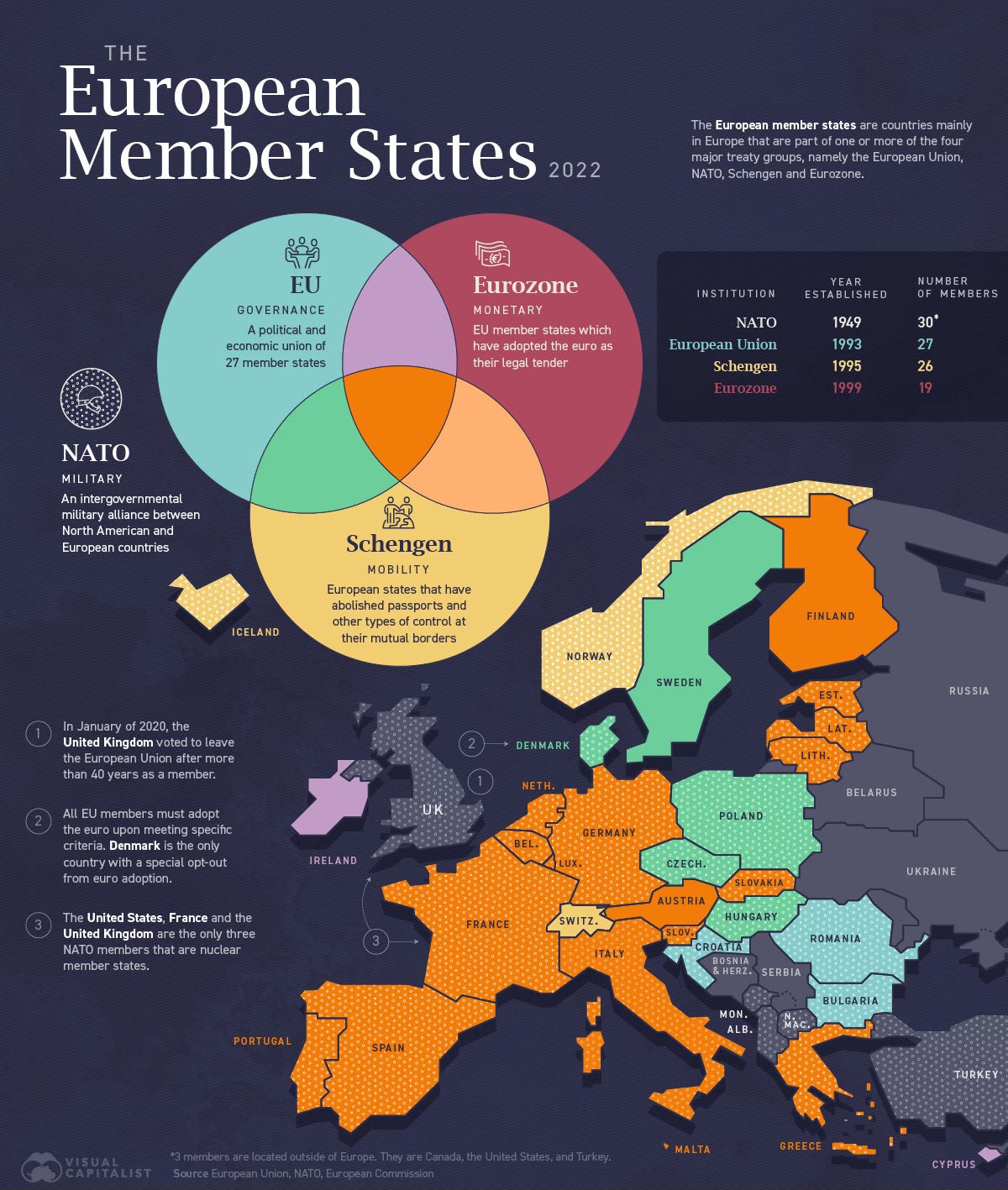

To broad frame it here, there is a strong logic for America to promote all sorts of “unions” with Latin America: like a common labor union that would allow freer movement of workers (in effect, reforming our current immigration/work visa system that makes it almost impossible to legally immigrate here and encourages migrant workers to stay forever lest they can’t make it back the next time economic conditions favor their participation), or a common visa union like the Schengen Zone in Europe (an area comprising 27 European countries that have eliminated border controls at their mutual borders), or a common security union like NATO, or a common currency union like the Eurozone in Europe. In Europe, you can mix and match from that multinational menu, as seen in the graphic below:

So, many ways to skin this cat.

[Tom spots Ramases, his 17-pound Siberian, suddenly glaring at him from his plushy.]

But … in each instance — for now — none of these paths conquer the WYR? test. There are clear pros and clear cons and the latter prevails, making the effort just not worth the stress. Then there’s today’s ethno-nationalistic populism that makes all this a moot discussion in the here and now (inconceivable!) … until enough time and change passes for that mountain of uncertainty to be summited.

Understand this: trade deals and integration schemes in general do NOT come about during good economic times, because no one then sees the point. Instead, they come about when economic times are bad and everyone is willing to try something — almost anything — to get things moving again.

So, what is dollarization?

Two forms:

Soft dollarization: where the US dollar competes with the domestic currency (e.g. the peso) as legal tender, rather than fully replacing it.

Hard dollarization: where a country completely adopts a foreign currency, like the US dollar, as its official legal tender, replacing its domestic currency entirely.

Which states have soft dollarization?

Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay.

Which states have hard dollarization?

Ecuador, El Salvador, and Guatemala, plus — of course — the OG itself, Panama (1904).

What are the benefits of dollarization?

The primary benefits of dollarization include stability in exchange rates, faster development due to increased foreign direct investment (FDI) and financial portfolio investment (FPI), lower interest rate premiums on government and corporate debts, and cost-effectiveness by reducing the expenses associated with printing and maintaining a domestic currency.

Does dollarization encourage foreign direct investment?

Dollarization can provide the direct benefit of encouraging outside foreign direct investment (FDI). When individual investors or corporations see that the local currency of a region is already established, and they do not need to incur exchange rate fees or monitor currency fluctuations, they may be more likely to invest and expand operations into that country.

Companies will see that the income they incur while conducting operations in a developing country utilizing partial or full dollarization can minimize their risk and give them an income stream in a stable currency.

What are the downsides of dollarization for the country in question?

Loss of “seigniorage” revenue (profit from issuing its own currency) for the government.

Loss of monetary policy autonomy and the ability to act as a lender (central bank) of last resort.

Difficulty in reversing dollarization.

Potential damage to national pride and sovereignty.

Exposure to external shocks due to an inability to devalue its currency.

The big thing is that the dollarizing economy makes itself subject to bad things happening inside the US, or bad policies. Then again, how do we compare to local doings?

What does dollarization mean for the US?

Dollarization can lead to economic stability, lower information costs, mitigate exchange rate risks, and promote bilateral trade between dollarized countries and the US. Additionally, dollarization can enhance credit ratings, improve access to international markets, and reduce debt restrictions for countries adopting the US dollar.

More generally, dollarization is perceived as a move towards low inflation, fiscal responsibility, and transparency, which can benefit both the dollarized countries and the United States by fostering economic integration and financial market closeness

So, overall, the United States should welcome dollarization in Latin America as it can strengthen economic ties, promote stability, and enhance financial integration between the regions.

Unless you don’t want that.

So why hasn’t dollarization happened more fully across Latin America?

Good question.

A lot of conditions need to come together to sort-of force this leap of fiscal faith, remembering that, once you do this, you can’t really go back, at least without even more pain.

There are a lot of myths about dollarization, which, in this article, the Cato Institute, attacks as false:

Dollarization leads to a loss of competitiveness and weak growth.

False: The main advantages of dollarization are a) it ends currency devaluation / depreciation b) it prevents the political class from monetizing the debt and causing high inflation à la Argentina …

Because growth has been slow in Ecuador and El Salvador, dollarization has not succeeded there.

False: Ecuador has not put in place the right supply‐side policies to generate Panama‐like economic growth, and El Salvador has backtracked in this respect since the 2000s. Dollarization is not a silver bullet. It needs to be accompanied by other pro‐growth policies that have been absent in Ecuador and El Salvador, thus their mediocre growth since they dollarized in 2000 and 2001 respectively.

Nonetheless, dollarization has succeeded in both countries because their dollar regimes prevented fiscally profligate, hard left‐wing governments from de‐dollarizing, re‐introducing weak currencies, and monetizing the debt …

Dollarization failed in Argentina in the 1990s.

False. In the 1990s Argentina had a currency board that exchanged dollars for pesos, a system and that is sometimes confused with dollarization …

The loss of monetary sovereignty leaves a country at a disadvantage due to the inability to counter external shocks with monetary policy.

False. As Hinds writes, Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador have all “calmly endured the 2008 and COVID-19 crises with much lower interest rates than in the rest of Latin America” …

Dollarization can lead to very high unemployment levels because of external shocks, while flexible exchange rate regimes can withstand such shocks far better.

False: Panama and Ecuador have proved that dollarized countries in Latin America can maintain low unemployment levels compared to non‐dollarized peers, even those with independent central banks such as Brazil and Colombia …

The Federal Reserve oversees all monetary policy for dollarized countries.

False. Although dollarization does take away a country’s ability to set its own interest rates and print its own national currency, while dollarized countries’ inflation rates tend to merge with those of the United States, liberalization of the banking system can grant an important degree of independence …

Dollarization is a U.S. imperialist policy.

False. No official institution in Washington supports or promotes dollarization. The White House and the U.S. Congress are usually disinterested in the monetary policy of Latin American countries. On the other hand, the large multilateral organizations, namely the World Bank and especially the International Monetary Fund (IMF), tend to oppose dollarization initiatives. For instance, when former Ecuadorean president Jamil Mahuad dollarized in early 2000, he did so against the express wishes of the IMF and the World Bank. Unsurprisingly, current and former IMF economists now oppose Argentina’s potential dollarization.

My point is this: When I speak about North-South integration, I think we need to consider every path as being on the table — eventually.

From today’s perspective, despite all that I’ve noted here, pervasive dollarization of Latin American economies isn’t in the works. As for the US Government? There is no strong push one way or the other. It just strikes most, I imagine, as a bridge too far with everything else going on. Or much like the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) ended up being after its “launch” by the Clinton administration way back when. There’s just not the urgency, as we’d rather work the Drug War and the Border Crisis. We get motivated to work the symptoms but not the disease.

But think ahead to an America where close to one-in-three Americans are Latino.

Imagine also a border crisis that’s maybe 20 times worse than it is now.

Where drought-driven famines put families on the move out of a sheer survival instinct.

Do you really think we’re going to shoot ’em all?

Do you want to live in a country that even contemplates that outcome?

When the choices get REALLY hard, then you can more easily surmount the WYR? test.

Because, at that point, the answers will come fast.