Steve Martin’s Wild and Crazy Guy tour was my first concert experience and my first contact high. It unfolded at the Coliseum at Madison WI in the late 1970s, meaning I was still in high school. My sister Cathie got me a ticket and took me. We sat behind a group who passed around a sizable glass bong that I just could not figure out how they smuggled in. Whatever mood I was in, I was transfixed by Martin and his shtick, later copied by SNL’s Weekend Update, to tease audiences with a set-up that went nowhere. It just hung out there, oddly eliciting — by that well established point — big-time laughs, but, understand, that was only after years of his working that material and cultivating an audience that was in on his “joke,” which was that his material was often all set-up and no punchline.

That’s the traditional comedy approach: the set-up describes this weird situation full of tension because it just doesn’t seem right (Where’s he going with this?), but then that tension is punctured by the punchline (Oh! I get it! He’s really a horse!).

Martin wanted to change all that, and, if you’re looking for a good historical documentary on what that meant to the world of American comedy, see the first part of this two-part documentary:

Martin found the traditional setup-punchline structure unsatisfying, as it often elicited automatic, predictable laughter, which drove him nuts. He wanted to create a more genuine, spontaneous reaction from his audience — almost against their will. By removing punchlines, he allowed the audience to decide when to laugh. By building tension (set-up) without release (punchline), he theorized that the unresolved tension would eventually lead to laughter as the audience itself decided where to laugh and which parts struck them as funny.

Weirdly meta, but there it was.

Eventually, once Martin became huge and was the first comedian to ever fill arenas all over the country, the jig was up and he needed to retire the persona. He had achieved a sort of Beatles-like call-and-response dynamic with his audience, as they, having been conditioned to accept his delivery, started laughing at totally predictable points. He became, almost like the Beatles, an animatronic version of himself on stage (he wore the white suit so he could be seen from a distance in arenas): he was just there to trigger the laugh points like the Beatles were just there to trigger the nonstop screaming — quite the achievement, and yet creatively unsatisfying.

So, that’s why he quite standup and never went back — like the Beatles with live performances. Martin had accomplished what he set out to do in that realm and he wanted to go into other areas.

Fascinating, right?

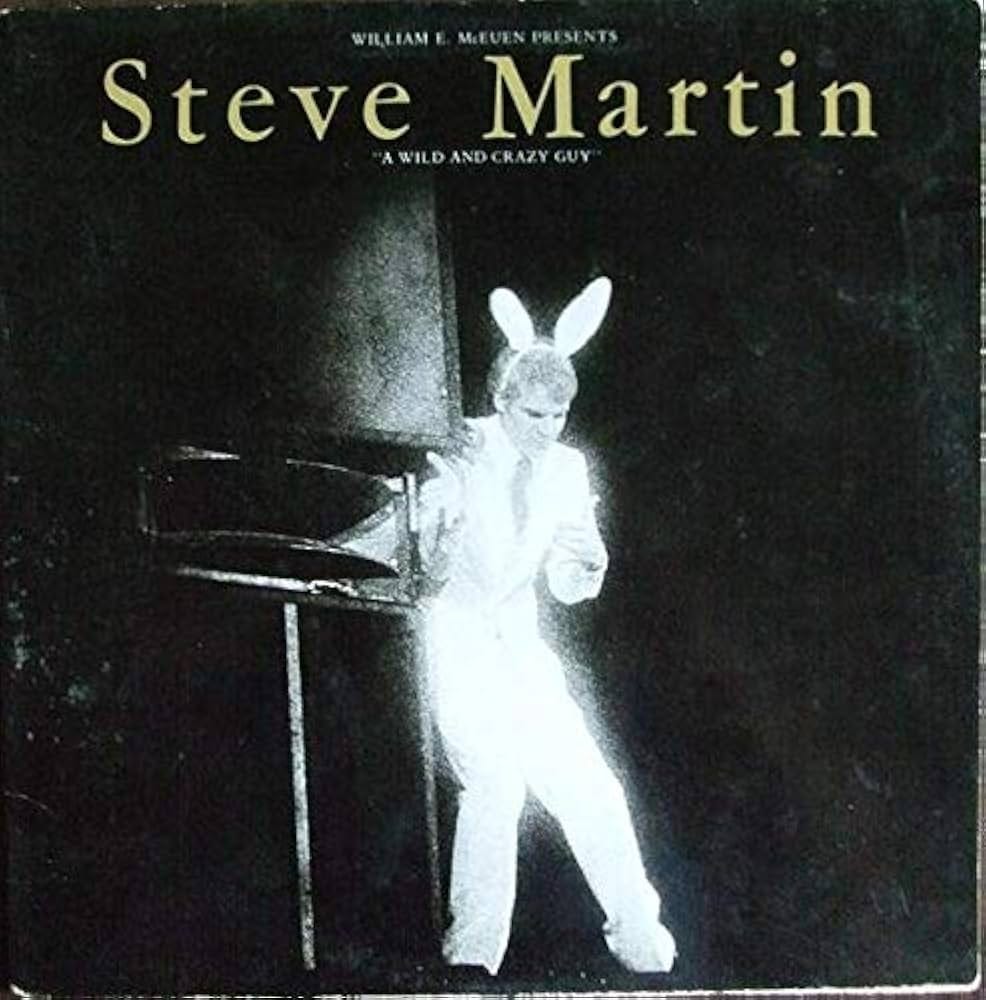

I purposely modeled America’s New Map on Martin’s approach: I wanted it to be one huge set-up on all these colliding throughlines (climate change, demographics, rise of global middle class, re-regionalization, shift to North-South dynamics) without providing the punchline (essentially, the means of North-South integration) in any detail beyond that Americas-First Grand Strategy.

That frustrated plenty of reviewers, who criticized me for not having enough details on the way ahead … because, you just know that the best grand strategies are complex flow charts detailing every step in the process!

But I wasn’t aiming that far: I just wanted to alter the audience’s way of looking at the world and let them come to their own “laughter” points of recognition and release.

This is why I always say that the best response to the book or a speech is: I’ve been saying the same thing for years but just was never able to put it together like you did here today!

In short, you want the audience to get there on their own — solely on the set-up.

As for the punchline?

Well, that was simply beyond my capacity at this point in my career, along with being too varied and out there for any one person to describe in advance. I can cite the Zone of Turbulence but I can’t tell you all the ways it will change you, your business, your community, your nation, your content, or your hemisphere — in advance.

Here’s how I put it in the coda:

I have chosen not to present any detailed plan for executing the grand strategy here proposed. That is an admission of both how early we are in any such campaign—despite the clear strategic urgency—and the great complexity awaiting our future engagement. It is also my recognition that plenty of models exist out there for our examination, comparison, and reconfiguring—a task beyond any one book and arguably only achievable through listening to, and dialogue with, those hemispheric neighbors we deem most suitable for pioneering this path. Finally, I did not wish to impart the impression of this vision being somehow limited, in any application, to a small number of US government offices and agencies. As with all things globalization, I think our government enables while our business community creates and thereby leads.

My goal here has been to prepare you, the reader, for the inevitabilities lying ahead, along with opening your mind to possible solution sets that will invariably strike many of you as inconceivable from today’s fixed perspective.

I realize my arguments represent a bold leap for many of us who, just a few years ago, elected a president whose foreign policy mantra was to “build that wall.” But it is exactly in times like this that inconceivables succumb to inevitabilities. Better to bull-rush a looming problem than cower in waiting.

In his autobiography, My Early Life, Winston Churchill observed, “Scarcely anything material or established which I was brought up to believe was permanent or vital, has lasted. Everything I was sure or taught to be sure was impossible, has happened.” We must embrace such humility for the task ahead.

My humble thought was, if I attempted to get the punchline all down in sequence, you’d just get lost in those details and likely reject the vision-shifting accomplishment that was my primary goal: I wanted to show you all these new realities requiring new models, as my buddy Steve DeAngelis likes to say (New models for new realities — a formulation that grammatically puts the cart [punchline] ahead of the horse [set-up], but you get the idea).

It’s like we need a new math, or a new political science.

Here’s the part in the book (Throughline 1 of 7) when I argue for it, citing Steve in the endnote, because much of this material came from that white paper of several years earlier:

Modern political science began with the question, Why did Germany’s Weimar Republic fail in the 1920s, ultimately fueling both Nazi fascism and the Second World War? How did such a sophisticated political design succumb so completely to dark forces suddenly beyond its control? Recall that Adolf Hitler pegged an imagined global cabal of Jewish financiers as determined to enslave and ultimately destroy the German people and their way of life.

Future historians may well ask similar questions about America—as in, Why did the world’s most successful and robust democracy fail in the 2020s?How did modern globalization’s progenitor and longtime defender suddenly succumb so completely to such anti-democratic impulses? Why did this nation choose to demonize and sabotage its wildly successful creation?

To avoid such political collapse, America must relearn how to thrive within globalization. We need to account for its skyrocketing complexity and restructure our capitalism—as we have done in the past—to address challenges both old (e.g., class inequity, institutional racism) and new (demographic aging, climate change).

In the post–Cold War era, world leaders cooperatively responded to such system-perturbing shocks as the 9/11 terrorist strikes and the 2008 financial meltdown. When global institutions originally built to prevent a rerun of the Great Depression and WWII proved outdated and unwieldy, these leaders updated and reinvented them (e.g., expanding the Group of Seven [G7] into the G20), allowing globalization to march on in its wealth-creating whirlwind.

But something emerged in the Great Recession to arrest that momentum. Our world’s stabilizing pillar, its now-majority middle class, started fearing for their existence. Their keen suspicion of being hollowed while the rich became grotesquely wealthier drained our collective optimism. In America, this triggered a tsunami of angry voters flooding the “swamp” with change elections every two years.

Who runs for public office under such conditions? Primarily demagogues whose boundless narcissism and existential fearmongering fuel their self-image as celebrity saviors combatting inhuman opponents. As a result, America presently endures its worst cohort of political leaders since its late-nineteenth-century Gilded Age, or at least last century’s Roaring Twenties.

Both periods witnessed technological and economic advances arriving far faster than security and political adaptations, resulting in the widespread sense of events spinning out of control. In both instances, society’s greatest talent flocked to the private sector, while public service was popularly disparaged. Both tumultuous eras eventually triggered lengthy bouts of progressive reforms by which rigged economic landscapes were aggressively regraded into less uneven playing fields, in turn replenishing America’s social optimism and political stability. Finally, each national correction was spearheaded by a New York blue blood from the same extended family—first Theodore and then Franklin Roosevelt. Both presidents successfully recast public service as a noble pursuit.

Today’s angry America has reached the same historical tipping point. Our nation needs a new type of political leadership based on a new political science, one that decodes globalization by leveraging interdisciplinary knowledge, data analytics, and human cognition–augmenting artificial intelligence (AI). We need to apply to socioeconomic and political issues the same sort of big data effort that our natural and data scientists now apply to a host of medical and environmental challenges. We have the technology; we just need to stop vilifying science and scientists.

That new political science must begin with the question, How does today’s America surmount the wickedly complex problems triggered by globalization’s success?

These challenges are not insurmountable. Considering how far humanity has advanced these past seven decades, they are our best problems yet.

ENDNOTE:

12 Our nation needs . . . artificial intelligence (AI). My thanks to Stephen F. DeAngelis, president and CEO of Enterra Solutions LLC and Massive Dynamics LLC, for this analysis.

That’s what Steve clued me in on back before COVID when we collaborated on a white paper that we both felt was ahead of its time and so decided to abandon — or, better said, postpone.

Because that white paper ended up becoming the building blocks of both the preface and the coda of America’s New Map and, in truth, it was the baseline code for the entire book that neither of us were ready to write then.

Fortunately, for me, Scott Williams and Throughline came along to enable my “wild and crazy guy” portion of the equation: I wanted to use the book to break the past’s grip on your thinking (East-West, Cold War, containment, WWIII), fearing that America was succumbing to the lure of nostalgia as a way “ahead” that was really behind.

You know the image from the book:

Understand, Steve and I go back to 2004, just after he started his decision-science/agentic AI firm called Enterra Solutions, where I was an early, single-digit employee from 2005 to 2010, when my role at the firm had been consummated once Steve decided the domain in which the firm would pioneer its approach to AI (consumer product goods).

Since leaving the firm in 2010, I have remained in collaborative contact with Steve over the years, and the influence he has had on me is … well … evident in America’s New Map.

Recalling Martin’s philosophy of comedy, I’ve always needed my Steve to play omega to my alpha — his concluding punchline to my forward-leaning set-up, like when I described, in 2009’s Great Powers: America and the World After Bush, how Steve and I collaborated with Pentagon offices in developing and implementing our rapid-connectivity-building approach to nation-building that we called Development-in-a-Box. We pursued that business-to-business network build-up model with the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, with Steve himself on the ground for long periods over several years — sort of his own personal surge within the larger American one. Steve accomplished a great deal with Development-in-a-Box in the KRG, creating some of the underlying economic resilience of that still semi-autonomous region within Iraq — no miracles, but solid economic achievements that persist to this day.

Where Steve has taken Enterra Solutions and its cousin company, Massive Dynamics, these past 15 years is truly amazing.

My favorite online vid of theirs that I’ve shared here before is found at https://enterrasolutions.com/soi.

Why am I sharing all this?

Steve and I are back to direct collaboration, gearing up for a series of joint-presentations at major industry gatherings, as well as podcasts where we explore how his AI punchlines release the tension of my geopolitical set-ups.

For me, all hugely exciting — or, more accurately, my own release.

Much like my work with Karen Fleckner at Artesion on virtual utilities leveraging the IoT (internet of things) to manage water + power, and my emerging collaboration within Throughline Ventures with just-retired RADM Matt Ott on his cell-of-cells war-room methodology, I find myself back in my sweet spot role of strategic adviser to high-tech founders (the relationship I originally built with Steve two decades ago; and before that, with Howard Lutnick’s Cantor Fitzgerald through ADM Bud Flanagan [ret.]).

Someday soon, I’m going to get these three geniuses in the same room and watch how their Vulcan mind-meld blows up the entire universe, so don’t say you weren’t warned!

good read. in response to the passage of your book.. I've hesitated to press you directly for your thoughts on this subject (lest we tip into direct political punditry, my god!) but since its brought up here... does your vision of this progressive political renaissance fit with the current system we have? namely the two parties themselves, winner-take-all style elections, etc.. as a helpless spectator it feels *impossible* for the uhh... distinguished members... of either party to possibly take up this mantle...

and I admit I look somewhat wistfully at European political figures who appear at the surface level to be... educated, professional, dignified, motivated, statesmanlike, NOT 85 years old... gosh I swear we used to have that?

with the democrats it seems like the "next wave" really hasn't emerged yet... and for the republicans it seems like they've managed to unearth a bumper crop of uhh... well, lets be gentle and call them very grumpy 30 year old men who don't offer much promise for the future

its my perception that we get such poor politics because that is what our system rewards, the game itself may be broken

apart from generalized notions that such a progressive age will happen and/or MUST happen... what exactly would have to take place in our society to bring this about? my fear is that its insufficient to just wait for the current batch to all to wither away in their wheelchairs

a bit heavy for a comment but there it is