From America’s New Map:

Just as globalization enters its next, ever-more-complicated evolution, our senior leaders are instinctively eager to declare new cold wars with both Russia and China in what can be described as strategic reboots of beloved franchises within the Boomer Cold-War Universe (BCU). Every generation succumbs to a strategic Alzheimer’s in response to a world spinning incomprehensibly faster. They instinctively cling to their fondest memories: a simpler time when you could tell the players without a scorecard. As policymaking goes, though, this is a tragic retreat from reality.

Nifty WAPO piece that everyone should instantly recognize because we’ve all been talking about it — rather vaguely for the most part — for years now.

The observation that is undeniable: We all have trouble remembering what happened during the pandemic. It’s like this big haze in our head, almost like a dream.

Can you remember when it started?

Sure. Vividly.

Then what happened?

Oh … a lot of stuff. There was this weird time, I guess it was the first time I went to a grocery store, and everyone was just racing around, trying to buy this one thing and then get the hell out of there before they caught something from the other masked zombies.

Weird time, right? The people who checked you out at the grocery store were like these heroic figures — just for showing up to work.

Yeah, but we kind of hated them too!

Why, exactly?

You know, I just can’t remember. But people were really upset, I remember that.

I have these odd conversations with myself all the time, trying to reconstruct timelines in my head, which is something very meaningful to me, and the reason why I love documentaries: I really want to get the timeline down.

But I can’t manage that when it comes to sometime around … I dunno, 2019 almost, but then it didn’t really start until 2020. And, if you asked me how long it went, I am really unsure.

I remember getting my first shot, then another, then …

I remember seeing my Mom on her death bed. The hospital/hospice was weirdly deserted. So was the hotel where we stayed. Everywhere smelled of cleaning materials. It was like Vonne and I were in a cheap, filmed-in-Vancouver science fiction movie where the plot had too many holes to mention but the production values were just enough to create this creepy vibe.

I remember going to Lambeau and watching Tom Brady out-duel Aaron Rodgers at the NFC championship. My wife and I had almost the entire section to ourselves. I would walk up to the empty food stand, order my food, go back down to my seat for a play or two, then stroll back up and pay for it and get my brat, leaving it at the condiments stand for another stretch so I didn’t miss any plays. Honestly, I’ve had many dreams that made more sense than that day, especially the part when Rodgers threw into triple-coverage to Adams while another receiver ran free down the middle of the field on the last play.

I think it was the last play.

I never got a program for that game and I have collected one for every game I’ve attended at Lambeau since 2001, so it’s sort of a missing deposit in my memory bank. Did I really go to that game? Did it really happen?

From the WAPO piece, tell me this doesn’t ring a bell:

I can remember the beginning. I bet you can, too.

Not necessarily the actual day — March 11, 2020 — that the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (covid-19) outbreak a global pandemic. But the way the pandemic entered our life.

I remember the first event canceled “out of an abundance of caution.”

The email from school instructing us to pick up our daughter immediately, as if she were in danger from the moment the administration decided to close.

The it’s really happening shiver that ran through the public library, four hours before closing time, when a staffer informed us over the PA system that we had 15 minutes to get out.

The last dinner at a friend’s house, where some of us hugged while joking about whether we should hug, and others kept their distance (see also: the first social schism along the safety divide). The next night, the last party at our house and then, the day after, the first time we declined an invitation for fear of the virus. (We were also tired. So: the first covid risk vs. reward calculation.)

I should say: I live in Albany, New York, which mirrored the caution and the closings of New York City, but not its ferocious contagion rate and death toll. I don’t have a first morgue truck to remember or a first 7 p.m. celebration of health workers. Nothing so dramatic.

But the beginning was vivid all the same.

After that? It’s a blur.

I can remember feeling like it was always Thursday. I’m not sure why. but it always felt like it was Thursday.

I can remember waking up in the night and wanting to take all my clothes off and run down the street screaming something, but I never did.

But I wanted to — really bad.

I remember panic attacks when I rode my bike just to get out of the house. I would catch myself holding my breath as I passed people and then almost passing out from the lack of oxygen, at one point actually tearing off most of my outer garments so I could breath in the frigid air that suddenly seemed so thin that I was shallow-breathing like I was on some high mountain trail.

For the life of me, I was deeply unclear about this panic persistently waiting to erupt just below my surface. It had never been there before but then it seemed like a permanent guest in my head.

If you ask me, or even if I ask me, about anything after 2019, I just get confused trying to place it in some timeline in my head. It was like I was traipsing around some multiverse and none of it lines up.

What can I compare it to?

Three events in my life.

First, the summer I spent in Leningrad in 1985, studying Russian but mostly getting drunk each night with Russians of seedy reputation (black marketeers). If you ask me about any world events from the summer of 1985, it’s like I had that part of my brain erased. I was living inside this weird Soviet info sphere and that was that. Stuff may have happened around the world, but I was only dimly aware of it. Like most Russians in a world absent any advertising (truly odd), I spent most of my day trying to figure out where the hell things were — like this one store has vodka but it’s a couple of trolley cars away so we better get moving. Stuff like that, I remember, but time outside my bubble … didn’t really happen — much less register — in my reality.

I have often felt a twinge of that information deadzone whenever I would travel to China for extended periods, and it mostly had to do with China’s Great Firewall. You’d try to stay abreast of things, but your browser kept timing out and, after a while, you just learned to live with it.

Second great example, which unwittingly prepared us (my spouse Vonne and I) for life under quarantine: our first-born’s long battle with a Stage IV cancer — a fight that began in her second year of life and ran deep into her fourth.

For those two years, we didn’t go anywhere. We rarely left the house — just for work. We kept almost everyone away from Emily all the time because her immune system was so haywire. Looking back, the whole thing really did resemble the shelter-in-place period of COVID. It’s just that we were the only people observing that ruleset.

And man, did that piss me off.

All the weird interpersonal-but-public showdowns over masks that happened during COVID? I had practiced that volcanic anger many times across those two years. I was ready to punch people out all the time for trying to kill my kid, as I saw it.

I also have almost no memories of the wider world across 1994-1996. The whole OJ Simpson thing? I missed for some reason.

I remain fascinated with that blank spot, having watched every documentary or movie ever made about it. They’re like some treasure trove of lost Star Trek episodes.

The only reason why I can remember any of it is that I wrote it all down in the Emily Updates — my weekly blog post that I faxed/emailed/mailed to relatives and friends across those two years. I had this instinctive feeling that I’d forget it all if I didn’t.

And that’s exactly what happened.

When I go back now and read those entries, it’s like I’ve never encountered the material before, which is weird, because I’m reading my own writing.

Third example, which explains the other two a bit (at least to me): I can’t remember the last mile of the Marine Corps Marathon of 1991. I ran it by myself because my running partner pulled out at the last minute. My goal was to run just barely under an 8-minute mile the whole way, and I did, getting about two and a half minutes ahead of my goal of finishing below three hours and 30 mins.

But somewhere around mile 24, I remember starting to cry over this profound sadness I was feeling.

And then I don’t remember anything until somebody put a weird tinfoil sheet around my shoulders after the finish line.

And when I tried to remember that period of time, I would just feel really bad, like my brain just did not want to go there.

I found that really freaky, but it helped me later understand memory loss connected to trauma.

My time in the USSR was a benign trauma (info deprivation).

My memory loss with Emily’s cancer fight was truly reflective of the personal trauma I experienced — basically a post-traumatic stress disorder that later took some group therapy in the woods of Maine to get out of my system.

My memory hole on the marathon was just my body getting me through that moment out of sheer muscle memory.

All of those experiences, in retrospect, generated “temporal disintegration” inside my mind.

The weird thing about COVID, of course, is that there’s no one to tell that story to because we all lived it — at the same disintegrated time. So none of us really has a definitive grip on that period, leaving it all up for debate.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HEALTH: Distortions in Time Perception During Collective Trauma: Insights From a National Longitudinal Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The abstract:

During the protracted collective trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic, lay of distorted perceptions of time (e.g., time slowing, days blurring together, uncertainty about the future) have been widespread. Known as “temporal disintegration” in psychiatric literature, these distortions are associated with negative mental health consequences. However, the prevalence and predictors of temporal disintegration are poorly understood. We examined perceptions of time passing and their associations with lifetime stress and trauma and pandemic-related secondary stress as COVID-19 spread across the United States.

Just reading that makes me want to go huh? and exactly! at the same time.

This is one study among many, as the WAPO piece points out:

Study after study after study has confirmed what everyone I know has expressed: that the pandemic altered our sense of time, which has in turn warped our memory. One study from a year into the pandemic asked participants to describe their experience of time and then sorted their responses into formal-sounding but utterly familiar categories, such as “temporal rift” (“Everything that happened before the pandemic feels like it happened in some distant era, in the ‘Before Times’’’) and “temporal vertigo” (“The pandemic itself seems to be going on for both 10 years, and two weeks”).

The covid-19 pandemic, which to date has killed between 7 million and 20 million people worldwide, including more than 1.2 millionAmericans, is almost perfectly designed to be forgotten.

For starters, it had two modes, both of which resist memory. One mode was horrific. People saw loved ones die struggling for breath — or couldn’t see them at all because of safety protocols. Front-line health workers risked their lives and witnessed horrors in understaffed, underequipped hospitals. For those who experienced the pandemic as extreme trauma, memories of specific events are often too painful to revisit — and acute stress can make retrieving those memories more difficult.

The other pandemic mode was humdrum.

Sounds about right, right?

I have two great memories of that period:

Working for hours on end on this huge jigsaw puzzle of the world with my kids (we gave up after about 15 months)

Wearing protective gear to visit my unconscious Mom on her deathbed as she struggled to breath about once every minute.

The rest is all tenuous.

Do an O’Brien on my Winston Smith and I would deny it all — almost gladly and with relief.

As the WAPO writer points out, we lost all the things that make one day THAT DAY, which is why everything felt like Thursday to me all the time — the most vague of days where nothing really happens.

Time stretches out, unmarked, unshaped and, therefore, incomprehensible.

No kidding.

The weird thing is, Trump is so tied to all of this:

No COVID and he wins re-election in 2020 and we’re done with him by now.

But, no COVID and Trump probably doesn’t win in 2024, riding all that angst and post-pandemic inflation that nobody was honestly responsible for but which we all suffered nonetheless (and still feel).

In other words, COVID both broke Trump and resurrected him — perhaps, in history’s judgment — more than any other variable in our world today. Hell, the blank memory spot helped Trump plenty because nobody could really recall how bad we all felt during his last year, and thus we forgave him his sheer incompetence in running that shitshow.

But all such thinking is pointless, in the end.

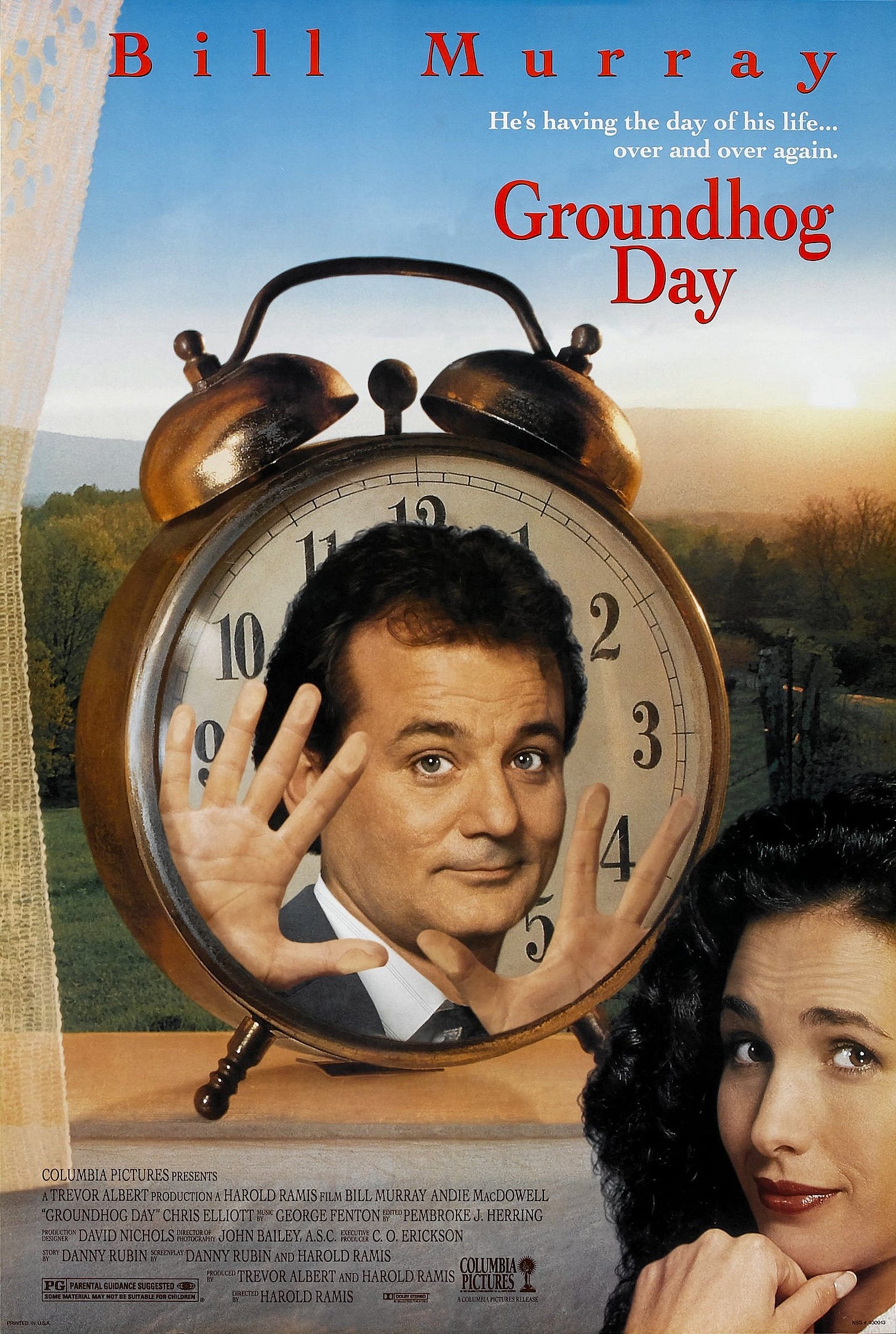

I often think of how the pandemic was such a Groundhog Day phenomenon: we were stuck in the same routine forever and our only escape were things like getting a rescue dog or learning how to play the piano or some other perceived self-improvement of the sort Bill Murray’s character chased out of desperation over his plight.

The temptation such experiences create within us is the desire to skip over the bad parts — getting us to the Adam Sandler film Click, where the main character wants to fast-forward through life’s mundane parts and only experience the good stuff, which, of course, becomes a meaningless exercise of no pain, so no earned gain.

Rejecting that sort of pain-avoidance logic is how I make my peace with Trump, whom I would definitely like to fast-forward through to get to whatever constitutes the recovery down the road (may be deservedly great, may be awesomely bad).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.