The CSPAN brief transcribed, with slides

The show repeats tonight (7:10pm EDT) on CSPAN3 and tomorrow morning (7:10am EDT)

Roger Hill:

Good evening.

I want to warmly welcome you all to Deloitte and to the book launch for America's New Map.

My name is Roger Hill and I have the privilege of serving as the sector leader for the defense security and justice sector here at Deloitte.

It is my privilege to be here today with you all for the book launch for America's New Map by the esteemed geopolitical strategist and New York Times-bestselling author Dr. Thomas Barnett.

Dr. Barnett’s book analyzes the current geopolitical landscape and unpacks the complex impacts of climate change and demographic dynamics, exploring humanity's collective future in a thought-provoking manner.

His book, and the strategic drivers he identifies, is a reminder of how interconnected our world is and how there are concatenated currents that require our care and action to preserve and advance our nation's security.

That is top of mind here at Deloitte: our dedication and commitment to national security runs through the very fabric of our firm.

We are proud for our decades-long partnership with the federal government, including within the defense security and justice sector, the services, and different agencies as the world's largest global professional services firm.

We know the value of agility in the face of national securities ever-evolving landscape.

Recently the firm has embarked on some exciting, pioneering work that addresses issues related to near-peer competition, which has become paramount in today's geopolitical context.

This is where our partnership with Throughline comes in.

We've been working with Throughline to develop a new global collisions lab.

Dr. Barnett's new book gets us thinking about how we should navigate these uncharted waters and to capitalize on the opportunities that they'll present in the future.

The lab features our new asset, which we call the Foreign Influence Risk Index, which is a powerful tool that helps clients better understand and address the influence of foreign actors.

In closing I'd like to thank you for being here and for sharing our passion and commitment to national security.

Now I'm going to pass it over to Scott Williams, who's the owner and founder of Throughline, for a few words.

Scott, over to you.

Scott Williams:

Good evening, so, as I have a couple of talking points, I'll try not to be duplicative.

I first met Dr. Barnett during my NAVAIR days in the senior executive development program -- got to go down to UVA, the Boar’s Head Inn, we all know what that was like.

And Tom, as well as Tom Friedman, were both presenters within the “global affairs of military strategy” segment, and I remember his PowerPoint, remember his visuals, and his “Law and Order” ch-ching.

So, later, I had the chance to hook up with him and what we're going to see tonight is really the hard work of Tom and our visualization team, and so, really glad to be here.

He's been decoding global complexity for 25 years or more.

The idea of bringing a lot of this thinking forward, into the world we're dealing with today, has been really incredible, and I’d just like to say, I think back to my Navy world and there were really two things that, as we started the company, one was the idea of bringing thought leadership into our client spaces and to the partnership with global firms, and so the idea of a partnership with Deloitte has been central to the company from the beginning: the idea of working together with Tom, and what we're doing here.

And the book is launching today – so, so excited, and with no further ado, Mr. Thomas Barnett.

Thomas P.M. Barnett:

So, we're going to have a Q&A following the presentation, and if you want to log on at menti.com through your smartphone, provide that code, you can ask a question and we'll cultivate those questions and we'll see how we can get through them as much as possible following this presentation.

So, I'd like to thank Deloitte for hosting this event.

The collaboration between Deloitte and Throughline and myself, putting these ideas together, it's been nothing less than spectacular for me.

I didn't anticipate writing another book, but when this offer came through, and the opportunity to work with data visual experts and with illustrators like Jim Nuttle, who drew most of the illustrations – all of the illustrations (his daughter had a hand in several of them as well) that you're going to see here tonight, it was just too cool, too much fun.

One of my favorite blurbs so far on the book is from an old colleague of mine.

She said it's like a graphic novel for futurists, and when she said that to me, she was concerned I would take umbrage at that designation, and I wrote back and I said, “that's absolutely fantastic,” because that's really what we're going for.

We're talking to younger generations.

The book is geared for Millennials and for Gen. Z, because this is a grand strategy outline for how we can deal with things: huge structural changes like climate change, like demographic disparity between North and South (the South with a 2 billion youth bulge still to be processed; the North experiencing what you could describe as demographic collapse in several instances – China already depopulating), and then that global middle class that's everything in the next 20-30 years, which is largely centered in the global South.

So, what I'm going to argue here is that we're heading from basically an East-West kind of world to a North-South kind of world.

Those are going to be the dominant dynamics, and that, all by itself, is a big enough change to justify a kind of grand strategic thinking.

So, I'm gonna tell you: I'm the father of six.

I am deeply invested in the future, okay.

Black lives matter to me.

DEI, ESG, all that kind of stuff, you know. it's all very real and important and connects me to the future that these kids are going to have, and I like to point out, with my two millennials and my four Gen Z's, a lot of the things I'm going to describe here tonight, they've been living in that world the last 20-25 years.

I don't explain any of it to them.

They have to explain to me on a regular basis, you know, not to use certain terms and not to make certain expressions and not to use certain descriptors.

But they don't have to think or process this whatsoever, because it's a very real world to them and I try to remember them whenever we're writing and doing this kind of thinking, you know, these are the people who are going to step forward.

What I'm going to describe here is a zone of turbulence between now and, say, roughly 2070-2080 – at least.

Three structural changes (climate change, demographic collapse, and the emergence and the demands of a global middle class) are all going to intersect.

Any one of those three things would be a big enough structural change to kind of dominate a century, and we've got all three going on at the same time.

But the notion is, look beyond today's problems and ask yourself, what kind of superpower we want to be in 20, 30, 40, 50 years, because we're not going to be the same setup that we have now and go through all these tremendous pressures and changes over the next 50 years.

So, it's a thought experiment I like to start off briefings by, just saying, you know, everybody understands free agency, the concept of end of the season, you can sign with another franchise, you can move on, you can pick the team you want to be with.

As a Green Bay Packer shareholder, season ticket holder, just went through that problem with Aaron Rodgers and the New York Jets, okay?

So, very familiar with this image.

On a global scale, one day, free agency for nation states, individuals, parts of nation states, you could just decide, “I'm Oregon, I want to go with Canada instead of the United States and so I'm going to sign with the Canadians for the next 20 years,” or something like that.

So, put these five as the five major franchises: China, India, EU, the United States, and Russia.

The question I ask you to contemplate is, once societies are done, which brands would be bigger?

Who'd be turning them away and who'd be losing maybe so much so that they weren't a superpower at the end of that process?

I think we need to think along these lines as we move forward, because identity, citizenship, nationality … become one of multiple identities that young people, future generations of leaders can adopt, can undertake.

I think it's one of the reasons why patriotism and national identity are lower than they've been in decades, really lower than they've been in our entire history.

There's such a competitive landscape out there for young people and their identities and if we're not offering them the right kind of brand, okay?

Now, when brands fail in the supermarket, they take them off the shelf, and, historically, when nation brands get stale, get old, they get taken off of maps.

And the Soviet Union was a completely real thing right up to the moment when its citizenry no longer believed in it, and then it evaporated and that can happen.

That can happen to any country in the world, and we've got some experience with that sense of tumult in the last couple of years.

So, I'm gonna tell you a story in six parts.

The first one I'm going to describe is our creation.

My argument is the rules we took from how we integrated the United States, that's what we projected upon the world very successfully.

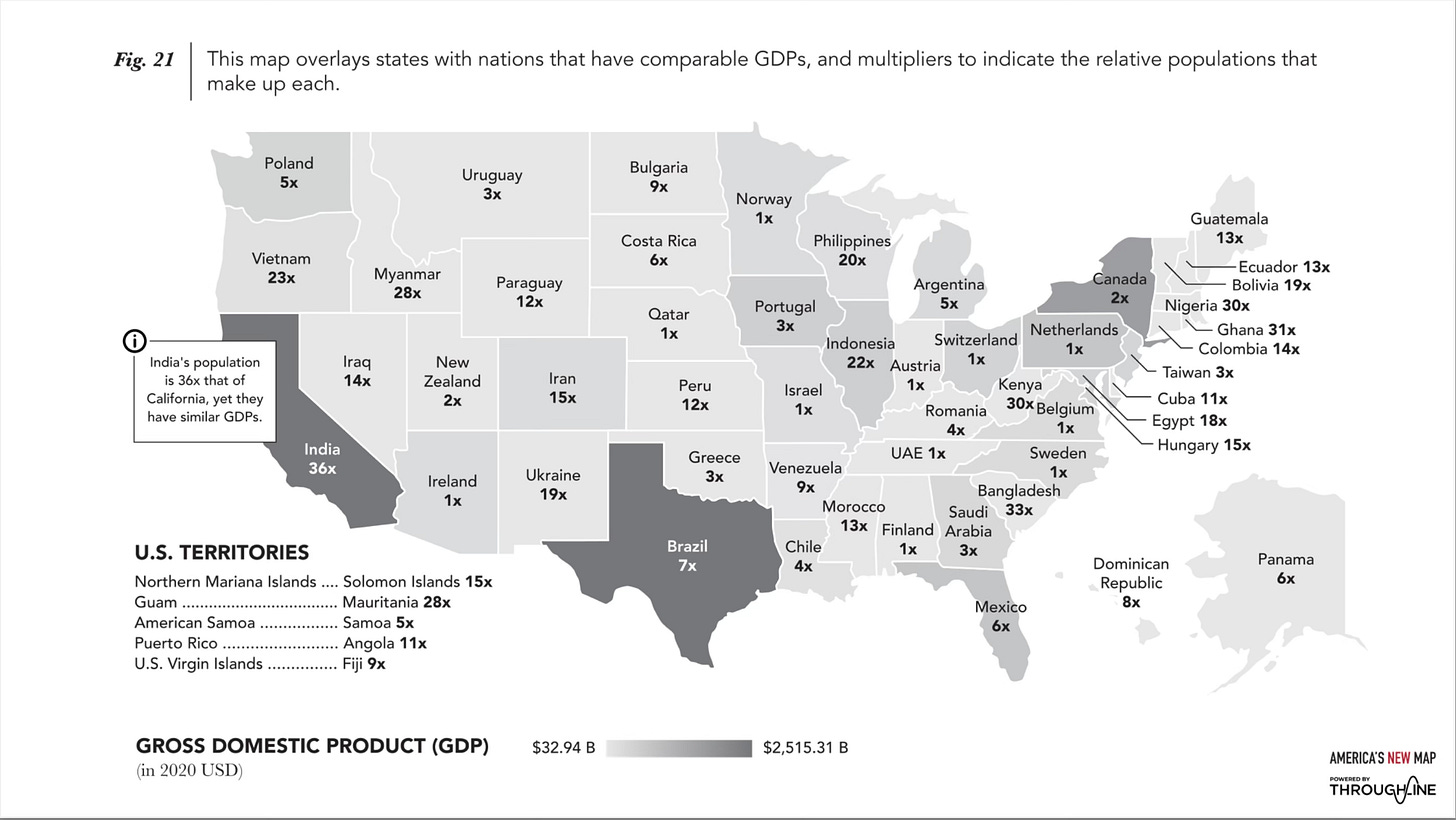

So, here's a map I love to draw.

Here's the state aligned with a country with the same GDP, noting the difference in population size.

So, India's GDP, roughly the size of California, even though it's 36 times the population.

Here's the rest of the map: you're looking at the freest trade in the world, the freest movement of money, goods, people around the planet.

You're completely unrestricted in what you can do inside this mini globalization, and, on that basis, we are the avatar for globalization, we're the source code.

This is two billion people, when you add them all up, seven times our number, which gives you a sense of how good we are doing this and how powerful it is to subject a country to that kind of opportunity, because not only were we creating, say, 25% of the world's GDP, we're creating 25% of the world's pollution too, okay.

So, we have a kind of an awesomeness to ourselves.

I'm arguing that we basically sought to replicate that around the planet after the Second World War.

Our goal was to end world wars.

If you look at it like that, we've been enormously successful, not just ending world wars but triggering the awesome growth of the global economy these last 60-70 years.

So, I'm telling you, we're the world's oldest and most successful multinational republic.

We're globalization in miniature.

I like to argue that our identity as Americans is the most important identity any of us will have.

We're going to have all sorts of other identities: Green Bay Packers season-ticket holder, father of six, okay, but collectively, individually, what we do as Americans alters this planet like nobody else and that's why identity with the United States is crucial, in my way of thinking.

We created a system that was built on rules – without a ruler.

We purposely sought to raise up other countries – peacefully rising.

Now that we've succeeded in doing that rather broadly across the world, we're kind of scared by our creation – that's the Frankenstein's monster imagery from earlier, because it's no longer a world that we can shape as much as it shapes us.

It's also not a world that resembles White America.

The future of globalization is overwhelmingly non-White, non-American, non-European, non-Western, and that freaks a lot of our political systems out, because they no longer see a future they recognize themselves in and that's where you're getting a lot of the underlying political polarization that we’ve gotten in the system.

So, there's the quick argument: America made a world, okay, but with that tremendous success come tremendous costs, okay?

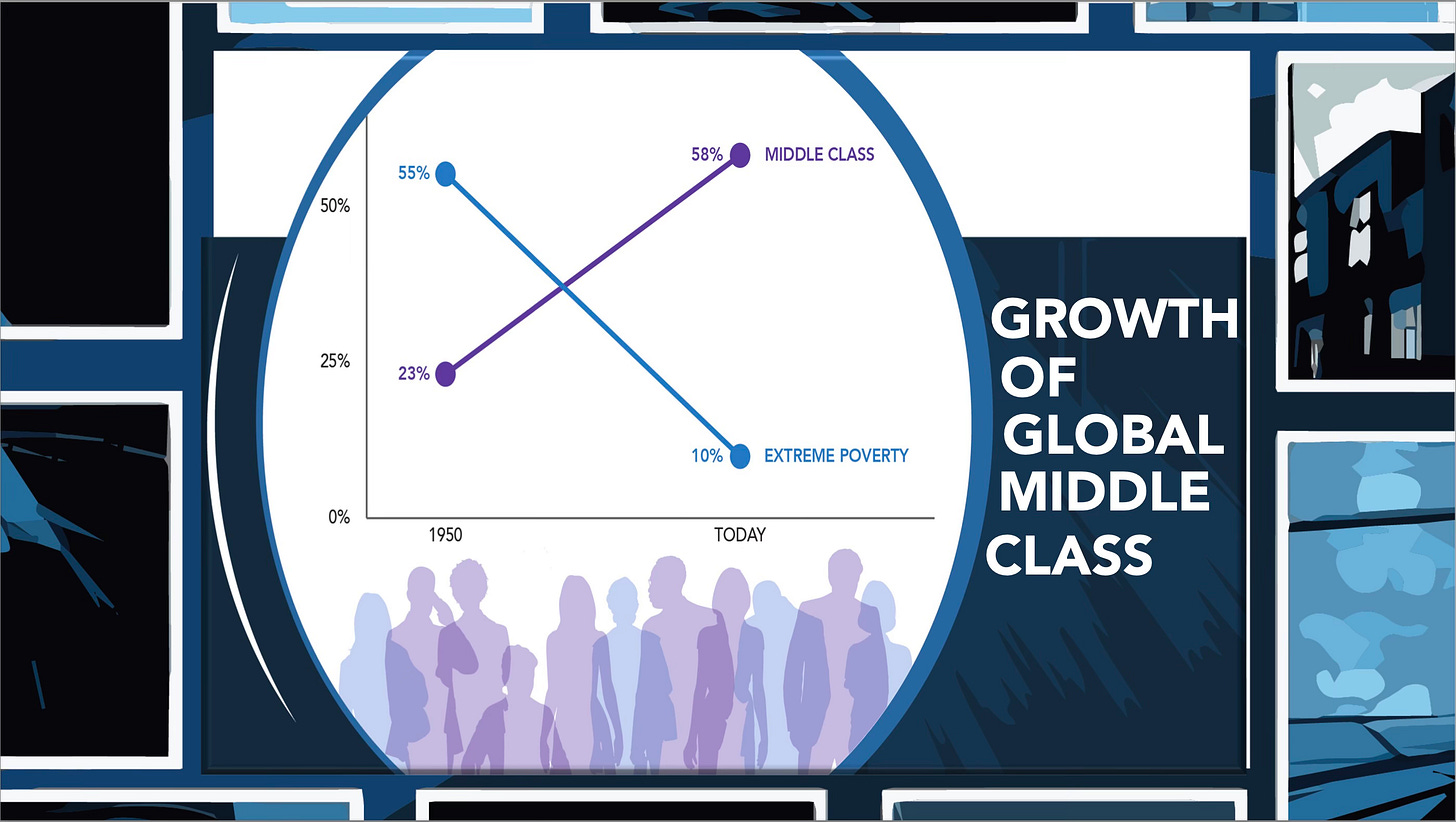

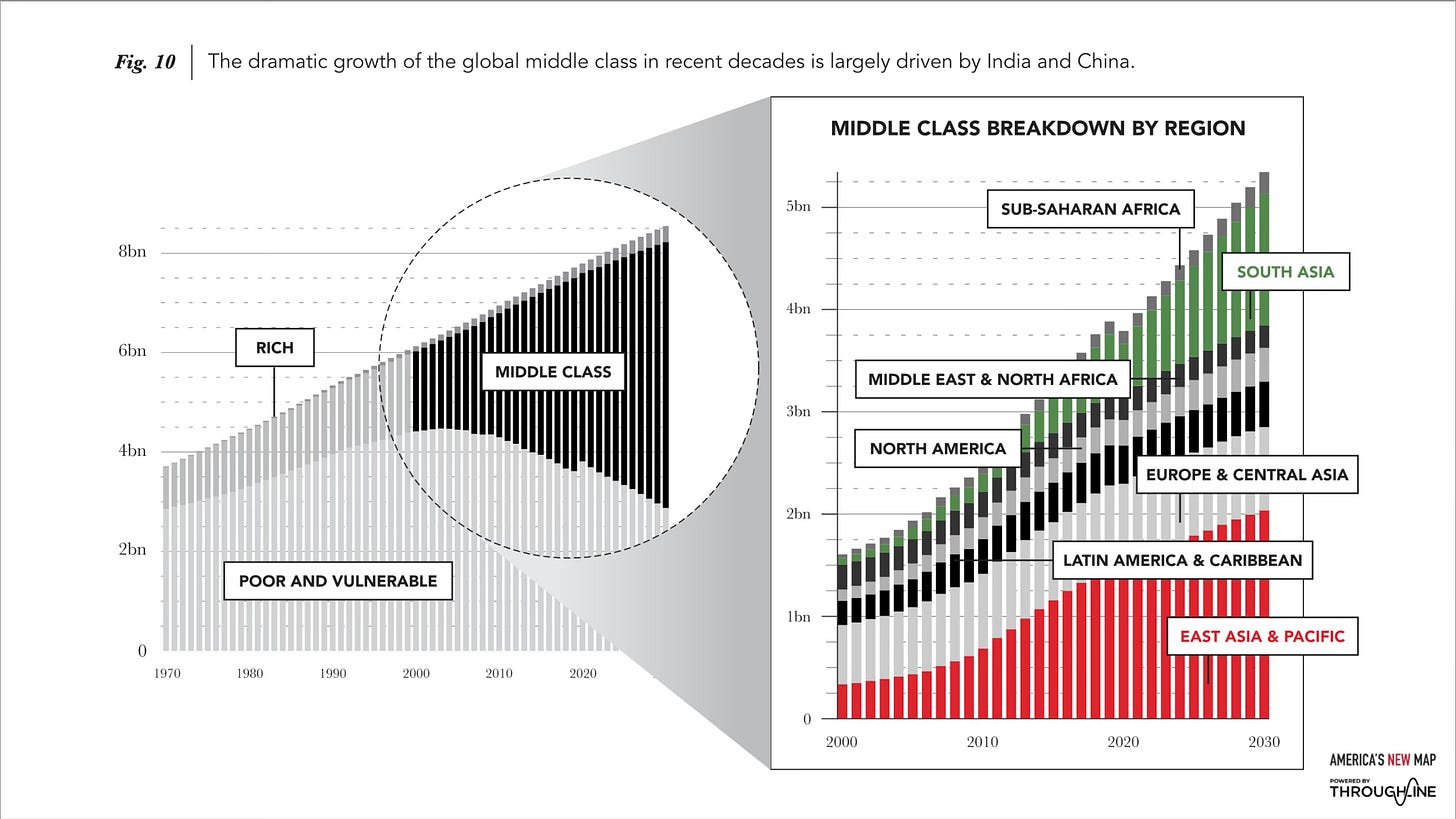

We created a global middle class.

I grew up watching these movies in Catholic grade school: it's all haves/have-nots.

The have-nots are only going to get worse.

It's all going to be pestilence, it's going to be famine, it's going to be just disaster upon disaster.

I was scared, growing up in the late 1960s/early 1970s, by all those educational films.

The truth was something that nobody predicted: the rise of a global majority middle class.

Okay, it's not the middle class we got used to in the 1950s or 60s.

I will tell you: for the average Millennial, they're closer to that global middle class, in terms of expectations, than the historical definition of the middle class in the United states.

They took the haircut, frankly, for the profligacy of the Boomers and the Gen Xers.

But the reduction of poverty, the growth of a global middle class, the greatest achievement in human history, and our country engineered it.

But with that came tremendous outcomes in terms of the environment.

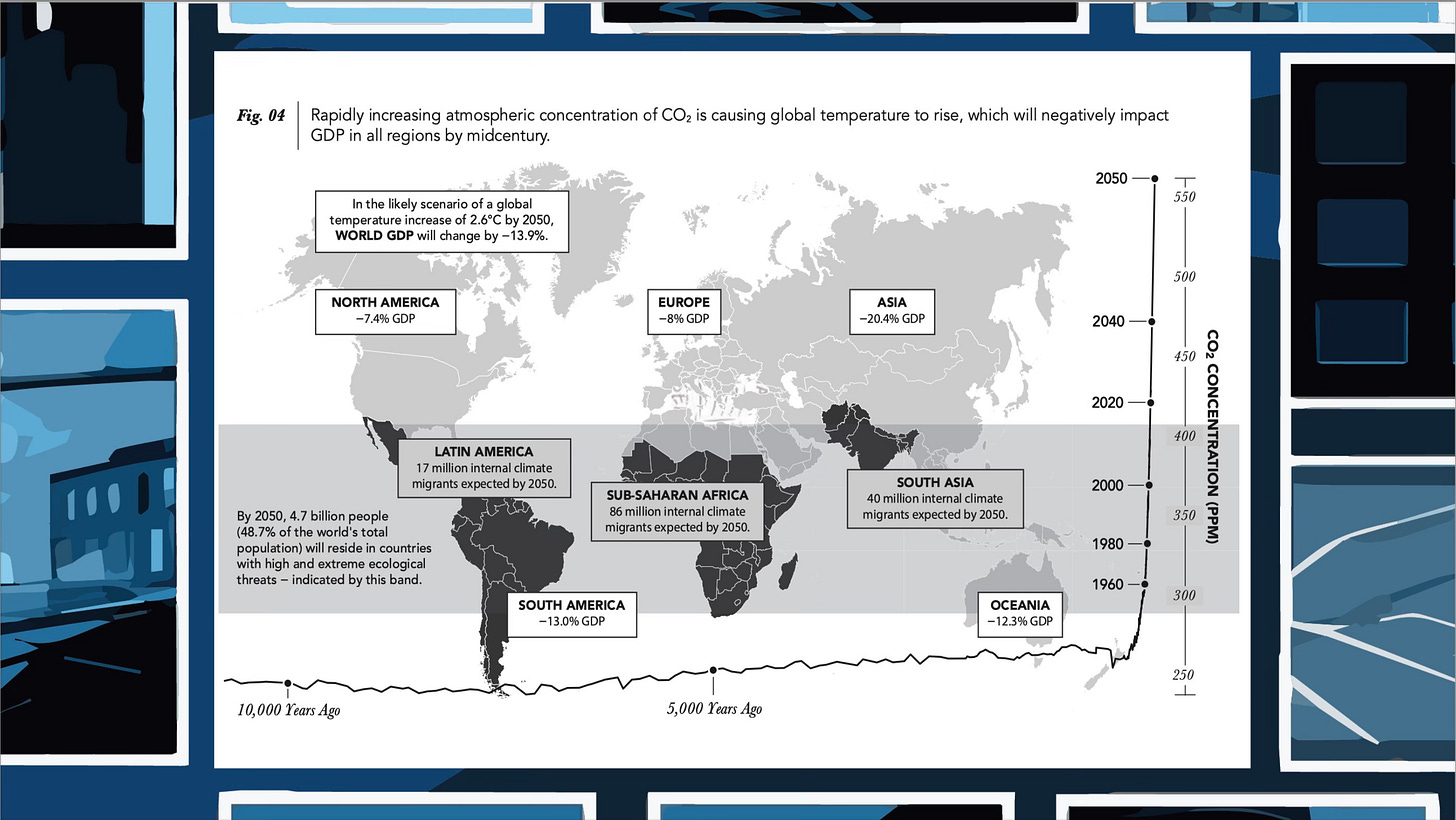

This band that we draw here in the cross, the middle, we call it, in the book, “Middle Earth.”

It stretches from the equator, 30° north and 30° south: more than half of humanity, the bulk of future middle class consumer growth, and 3-to-5 billion people are going to be subjected to temperature ranges and precipitation ranges historically associated with the Saharan Desert, which is not densely populated, okay, which has very weak governments because it's a tough place to live.

If you're going to put that many people under stress in that part of the world, you're going to trigger big-time change on that basis.

There's no doubt, when you add up all the things we've done to the planet: we've alternated the atmosphere, put a trillion tons of carbon into the atmosphere (a trillion tons is roughly equal to the weight of every building on earth today).

That's how much we shoved into the air.

In terms of the land, we've reformatted three-quarters of the land outside of Antarctica.

In terms of the water, we've acidified the oceans, we've altered the pH level of the oceans to a degree never before recorded in human history.

And finally, we're living through the 6th great mass extinction in this planet's history, overwhelmingly caused by climate change, overwhelmingly engineered by the United states, okay?

I'm not arguing against making the world a middle class-centric possibility.

I'm not arguing against that at all.

I'm just saying, with that tremendous effort, that tremendous success, comes tremendous cost, or what scientists identify now as the Anthropocene – this notion of the human epoch.

Okay, when Roosevelt and his wise men set in motion that international liberal trade order after the Second World War, they did not imagine that they were going to create a new geological age.

That's the power that we've unleashed.

Third point: North-South integration, alluded to it earlier, this alone is a huge change.

Think back to your Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs, and Steel): the wide part of the world ruled the tall parts.

Now it's better to be taller than wide, because tall means you’ve got options as climates shift.

So, Middle Earth, as we describe it, experiencing that tremendous difficulty.

We saw some of this, preview to us, during the Summer from Hell this last year.

Temperature ranges, precipitation ranges, water usages/shortages, where you've got the city of Phoenix basically saying it's too dangerous to go outside and we're going to have to curtail future development in Sun Valley as a response.

We see insurance companies pulling out of Florida and California, so some of these things have come into our mailbox in terms of bills and it gets harder and harder to deny it.

But we want to focus our attention on this Middle Earth band, because that's going to be put under such stress that either we start thinking about how we collectively deal with that stress or people are going to be put on the move big-time.

What happens with climate change is essentially two Australias’ worth of livable, arable land in the lower latitudes goes away – no longer arable or livable.

Two Australias’-worth of arable, livable land appears in the northern quarter.

I call this the greatest real estate transaction in human history.

No money changes hands.

Guess which side is unhappy about that transaction, okay.

So, if we're going to have this kind of benefit, this kind of change, we’ve got to adjust to it, because everybody is being put on the move.

Species all over the world are moving up in elevation and toward the poles – climate velocity.

My favorite Black Swan event right now, I just saw this a couple days ago: University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I went to college, has this fun tradition getting about 1000 [plastic] pink flamingos and sticking them in the ground in the main quad, because it's such a joke – pink flamingos in Wisconsin with our harsh winter.

Okay, pink flamingos showed up in Port Washington, about an hour’s drive south of Green Bay, the famous frozen tundra.

Okay, so my Black Swan event is actually a pink flamingo event that's telling us how nature is responding, and we either deal with that reality or we're gonna find ourselves building a wall that can't possibly keep that climate velocity, and everybody that’s gonna be put on the move with it, from entering our borders out of desperation.

That's climate change, now let's talk demographics, where the disparity between the South and the North is profound – still a youth bulge of about 2 billion in the South.

We’ve got demographic collapse starting to occur across the North.

The balancing act here is hard, like to distinguish between what happens in a demographic transition and how that allows your economy to connect to the global economy, because it's a very specific story and what I'm describing here is basically how you get connected, the golden ticket, let's say, to take your economy and put it in global value chains, if you're lucky.

And you achieve a demographic dividend by first lowering the death rate zero-to-five age range.

Eventually people start having fewer babies, but there's a lag between that discovery and that action and in that lag there's an artificially created larger-than-average generation.

Okay, we had one right after the Second World War, it was called the baby boom.

Okay, that's welcomed.

Then they grow up into teenagers – not so welcome.

We fear the crime, we fear the revolution, it's 1960s America, okay.

Then they age into the workplace and you’ve got your ticket to the global economy: lots of workers relative to dependents.

The problem is, you've got so much time to cash that in before you start stockpiling old people, and this is happening across the world.

My point in raising this is, every model that we've seen since World War Two has been driven fundamentally by a demographic dividend … with the United States, then it was Japan, until it was the Chinese, and now we're talking about the Hindu Miracle because their demographic dividend is about 500 million workers, is coming online next 10-to-15 years.

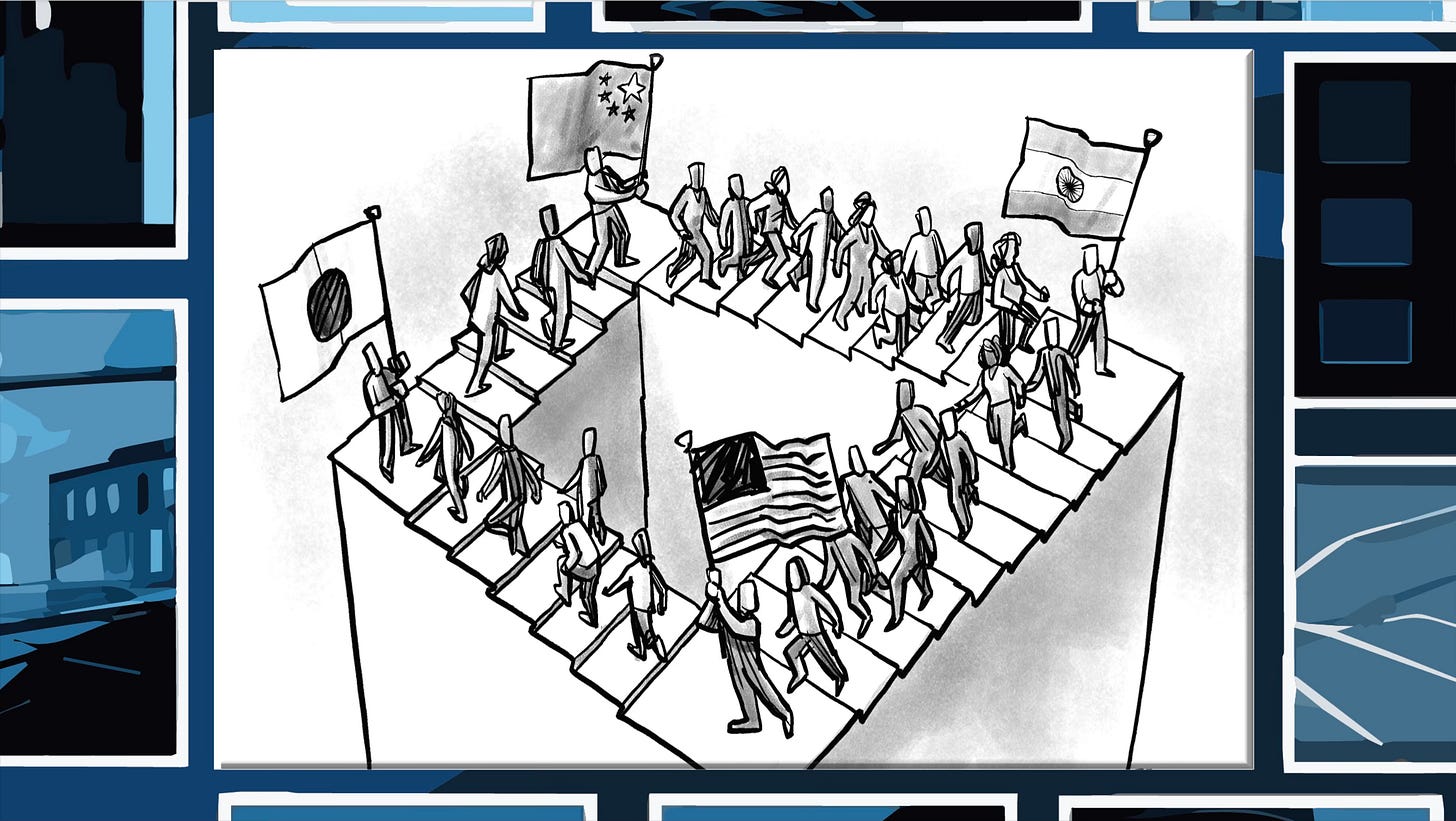

So, understanding that march is crucial to understanding how globalization unfolds and how we need to try to make that unfolding continue to succeed, my point with the global middle class (Throughline 4) is that the global middle class represents the target of superpower brand competition in this century.

It's not just getting access to the workers, it's getting access to all those consumers, okay?

The middle class is largely centered in that global South of that Middle Earth.

What does the middle class want?

The middle class, unlike the poor who want protection from their circumstances and the rich who, quite frankly, want protection from the poor, the middle class wants the hardest thing to deliver, which is protection from the future.

They have a good life, they want to preserve it, they want certainty.

That is the superpower brand competition going on now, as that global middle thickens.

That global middle class is overwhelmingly going to be, as I noted earlier, Asia, South Asia, East Asia as the primary sources.

The struggle to get access to this population, that has historically grown up with unprocessed, unpackaged, unbranded goods, and now they're moving into branded, packaged, processed goods.

We know, for example, from when you buy your first car, make your first presidential vote, when you collect yourself enough to focus on a brand, you tend to stick with that brand, often for the rest of your life.

With all that 2-to-3 billion new consumers coming online over the next 20-30 years, that's what China is as much interested in capturing as the resources and the supply chains, because having access to that middle class, making them happy, it's going to define the rule sets that govern globalization this century.

The EU has a model; I argue in the book it's a brilliant model.

They aren't integrating Eastern Europe because it makes them money right off.

They're doing that to deal with future problems and kicking those future problems and making them go away, so that when the Russians finally get around to getting mad-nasty again, they're fighting it in Ukraine instead of Germany, okay?

That's a tremendous strategic vision, I would argue, and the best display of soft power execution anywhere in the world.

We know what the Russian model is, it goes back to the old tsarist days: basically take hostages along the border and republics, basically going in and grabbing Russians who they encouraged to live in those places as minorities in the past, so that they can capture the larger entity that surrounds that enclave.

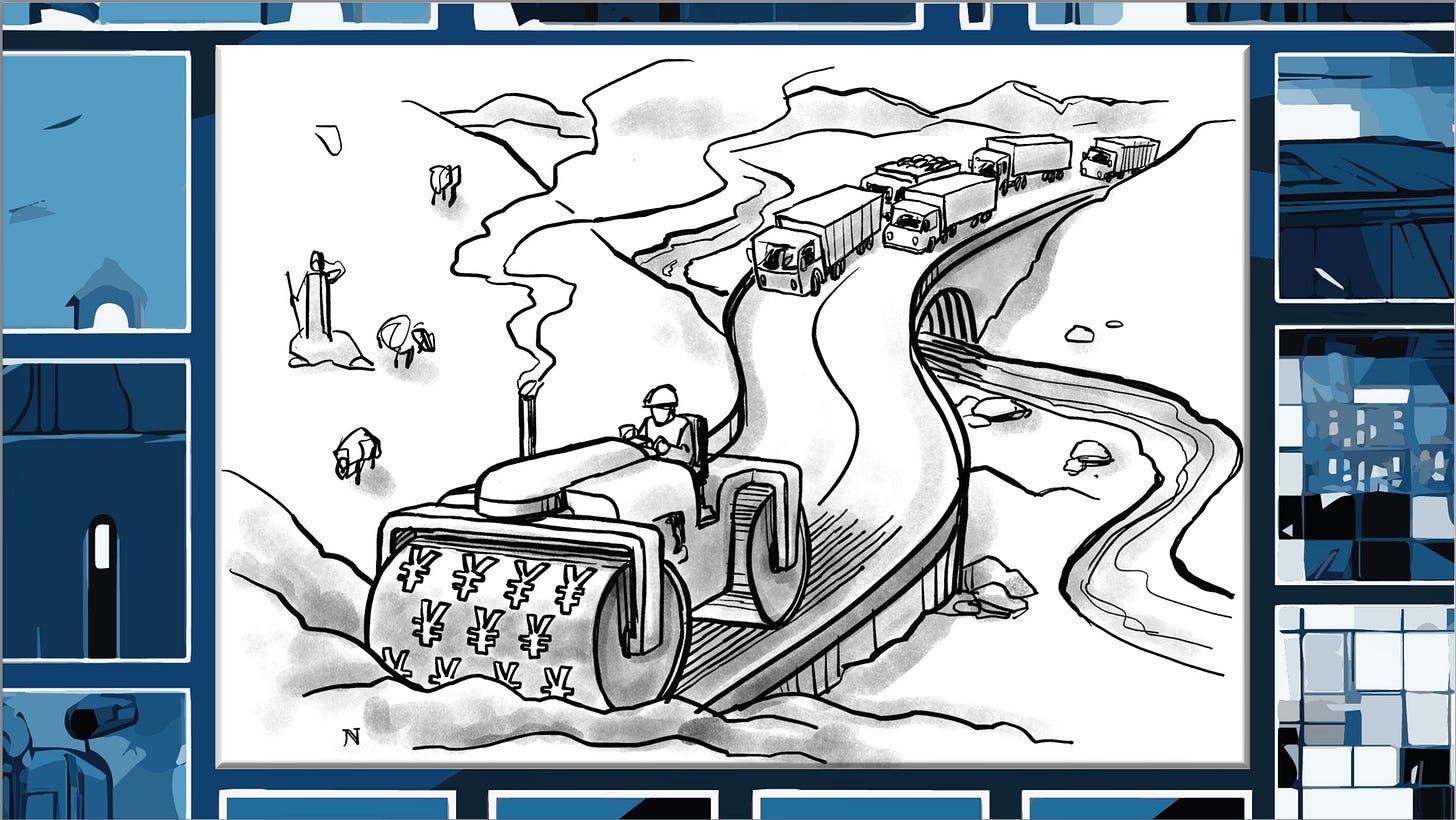

And then we got the Chinese with the Belt and Road, the connectivity force.

They come in, connect you up, and then they're eager to connect you also with 5G global networks, with all the backdoors they build into all their different network systems, they allow you to surveil your society and they allow themselves to surveil your society through the networks they've created.

And then we can't forget the Indians, because they're going to be the next new global power player in terms of cheap labor with their demographic dividend coming online, which is why I'd like to argue, even though we're kind of fixated on China inside the beltline here, that the real superpower competition or relationship of note in the 21st century doesn't involve us.

That involves the Chinese and the Indians and a very careful relationship that has to develop as this guy [China] moves up the production chain and starts having to invest and integrate the Indian economy into those value chains – much more complex even than what we did alongside Japan in terms of integrating the Chinese in years and decades past.

Meanwhile, I would argue the United States is not recognizing this future whatsoever.

We are fixated, primarily through our Boomer leadership class, with kind of trying to recreate that idyllic youth that we had in the 1950s and the 1960s.

We’re still relitigating all these social issues, as the Boomers love to declare war on all sorts of stuff, love to have fights dragged out and tooth-knocking-in kind of fights, and, honestly, it's been a real problem for us in terms of our image abroad and in terms of our national security leadership and vision, to be so overwhelmed by the kind of culture wars that we're engaging in.

This is my favorite drawing from the book: it's the idea that the Chinese are playing go, the Russians like to play chess, and the Americans like to play poker.

We like showdowns.

We're doing that right now in Ukraine, okay?

The Russians, they have no problem wasting pawn after pawn after pawn, they're doing that in the Ukraine.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are laying down their markers all over the planet, stone by stone by stone, playing go, and that's a real problem: the fact that we don't recognize the same competition that they're engaging in.

So, my tendency is to say the United states focuses on the gun, you know, we see a problem, we send people take care of that problem.

Our list of we-got-em bad actors, it's really long, okay?

Our list of countries we fixed by getting that guy … not so long, okay?

So, we think getting the bad guys creates the environment – secure.

They think creating a secure environment prevent the bad guy from arising – very different perspective, top-down versus bottom-up.

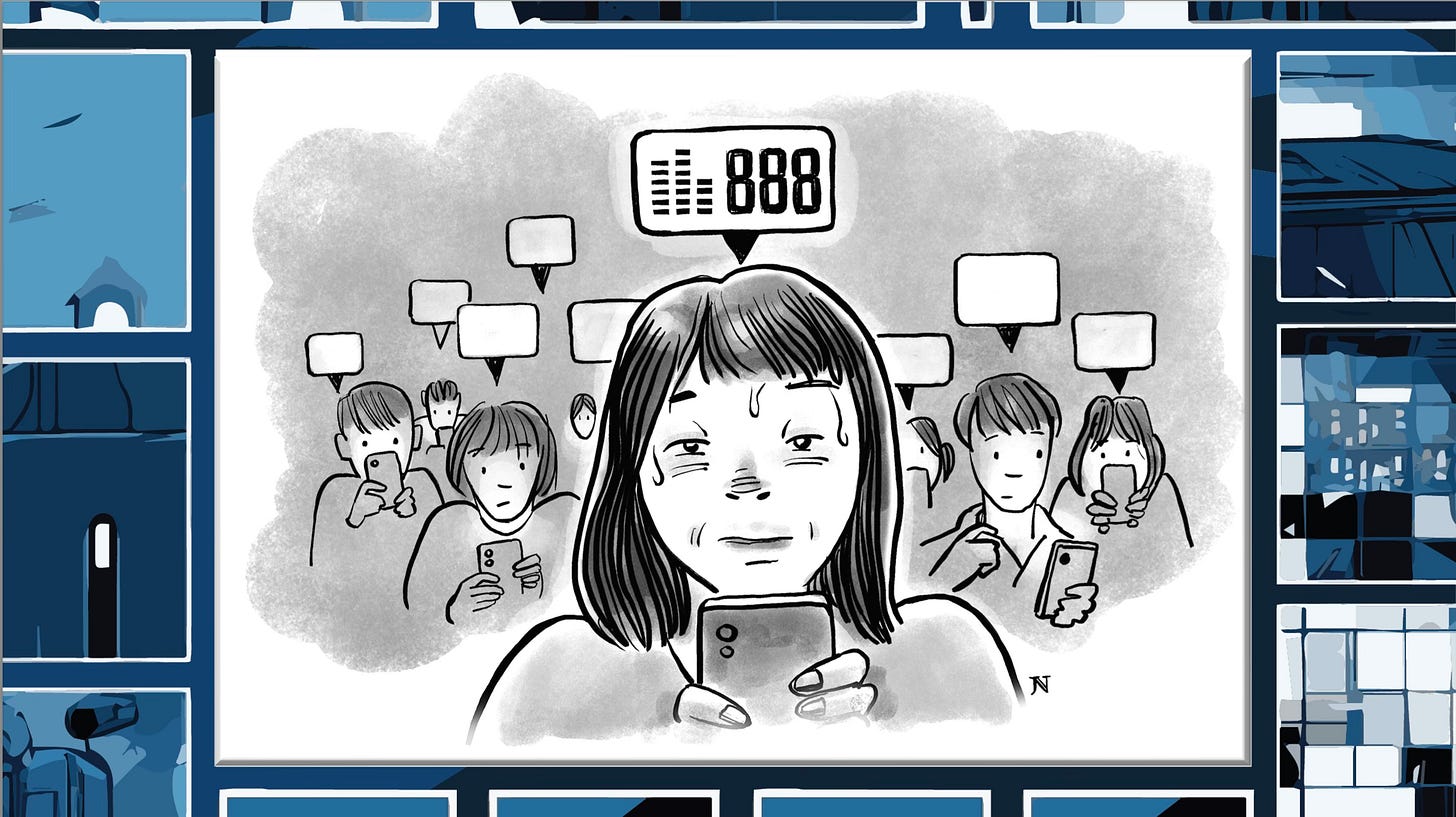

What China does with this approach, coming into your country, not just doing the connectivity with infrastructure but doing it in terms of 5G, their ultimate goal is to get you, the citizen of this country, in addition to what they're pioneering inside of China, to basically police yourself.

Social credit system: you get too close to a government protest, anti-government protest, your score goes down; you don't like a pro-government posting online, your score goes down; you end friendships with anti-social people, your score goes up.

Okay, pretty soon they don't have to act as your minder because you’ve got so many cues, you're self-policing yourself.

From our perspective, this is scary, this is Orwellian.

From the Chinese perspective, it's the enforcement of social harmony.

I'm telling you, what they're trying to do is basically commoditize things like prosperity, security, you know, community, that kind of stuff, by saying that, in effect, if you get it from the Chinese, it's no different really than if you get it from the United States.

It's basically the same package: we're just less frantic about it, we're less crazy and less unpredictable in our behavior.

And I will tell you, for a global middle class that's arisen around the world, this is a pretty good package, in large part because we don't offer an alternative to it.

What we offer are sanctions.

So, in a future were individuals can make up their own identities, okay, and have all sorts of identities, we're in a battle to put out the best package, the best brand, the best sort of connectivity.

We want them to want to join the United States in larger packages, in larger unions, because if they're not joining us, they're joining somebody else.

This battle, I will argue, overwhelmingly fought in cyberspace.

So, let's start wrapping it up: Throughline 5, why we're going to win this competition.

If the future is all about North-South integration, my argument is, we're in the best position for this – by far.

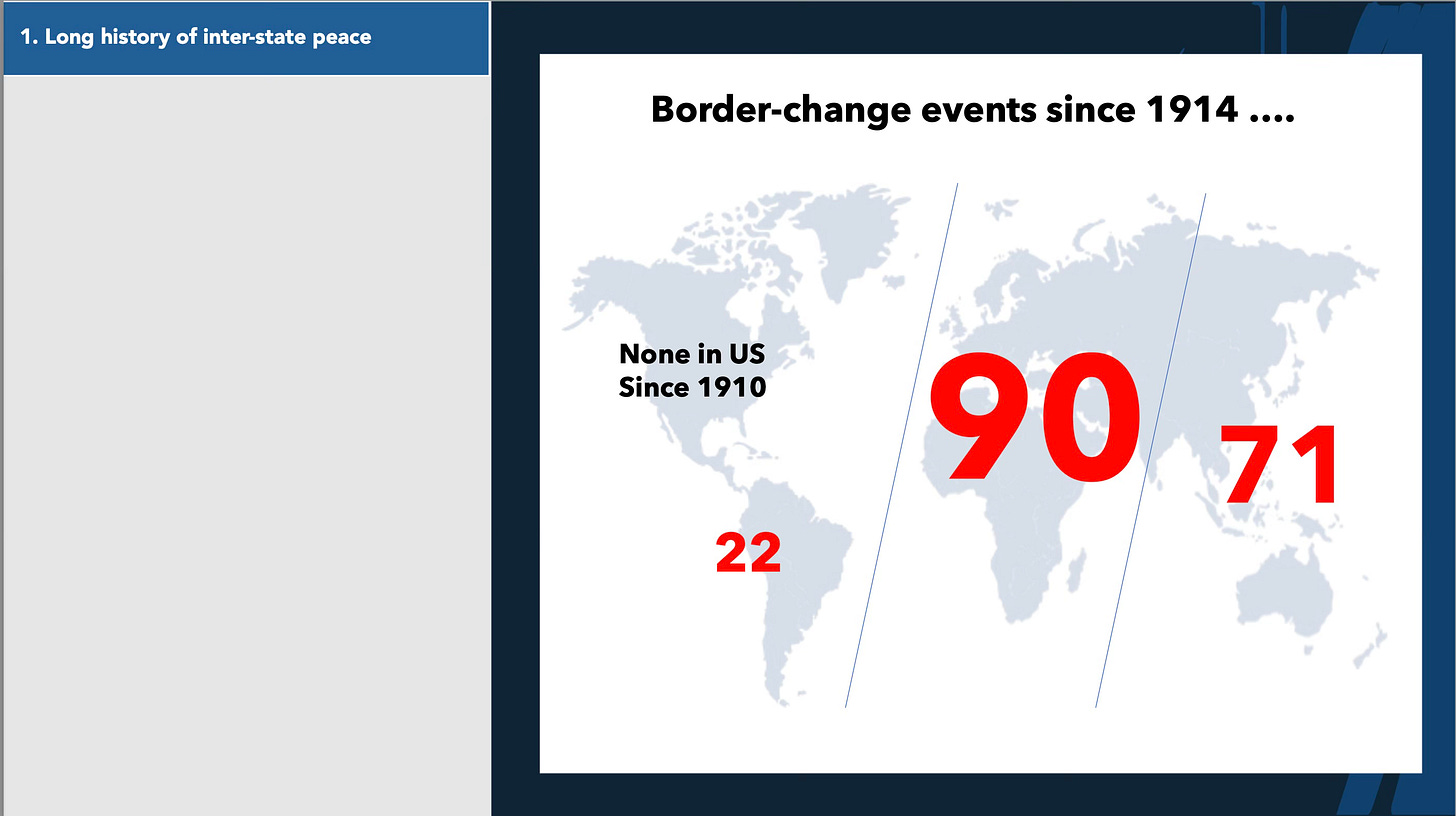

Border-change events since 1914: very stable in the West.

In terms of military superpowerdom, we are far and away the biggest player in the system.

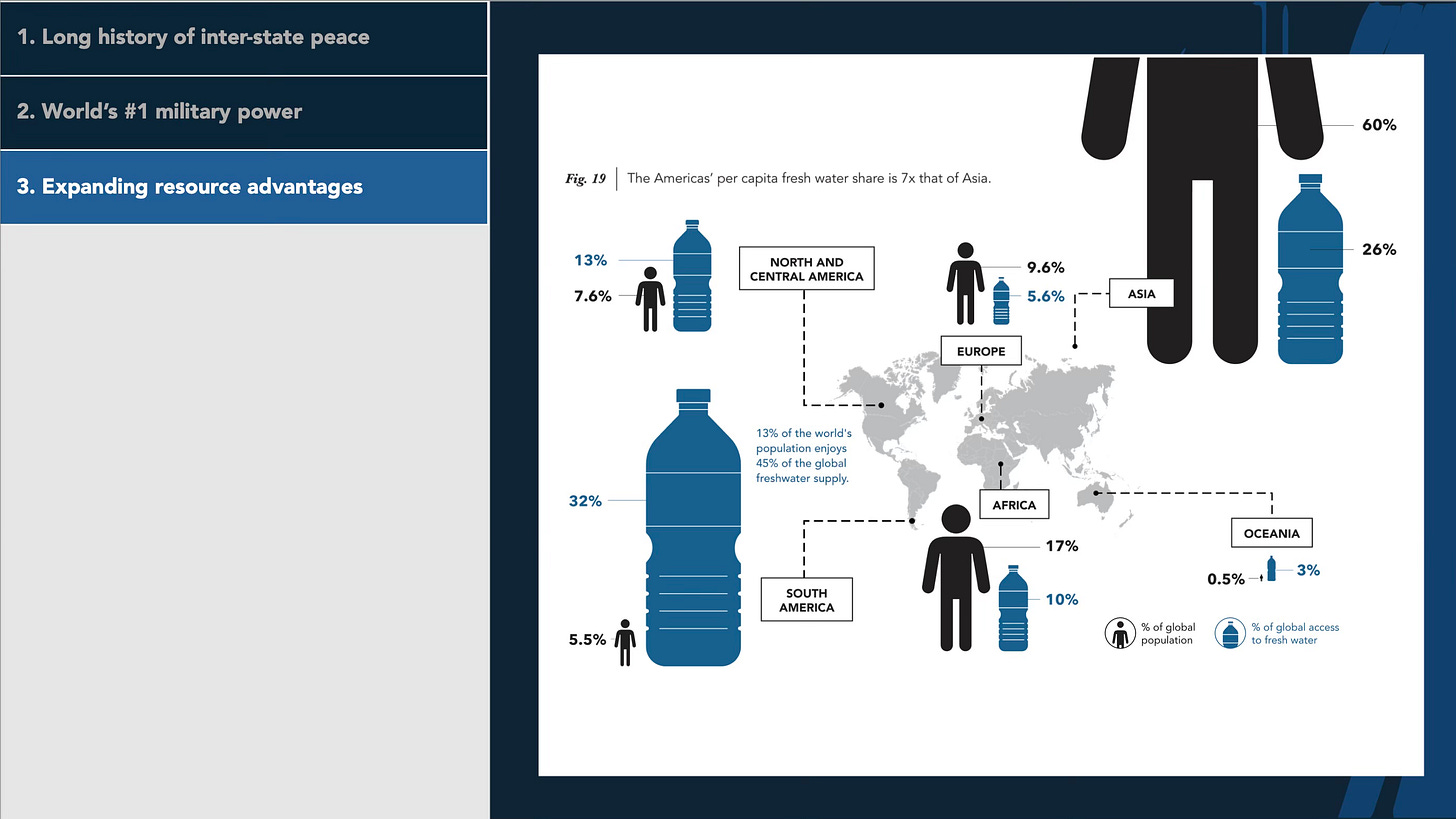

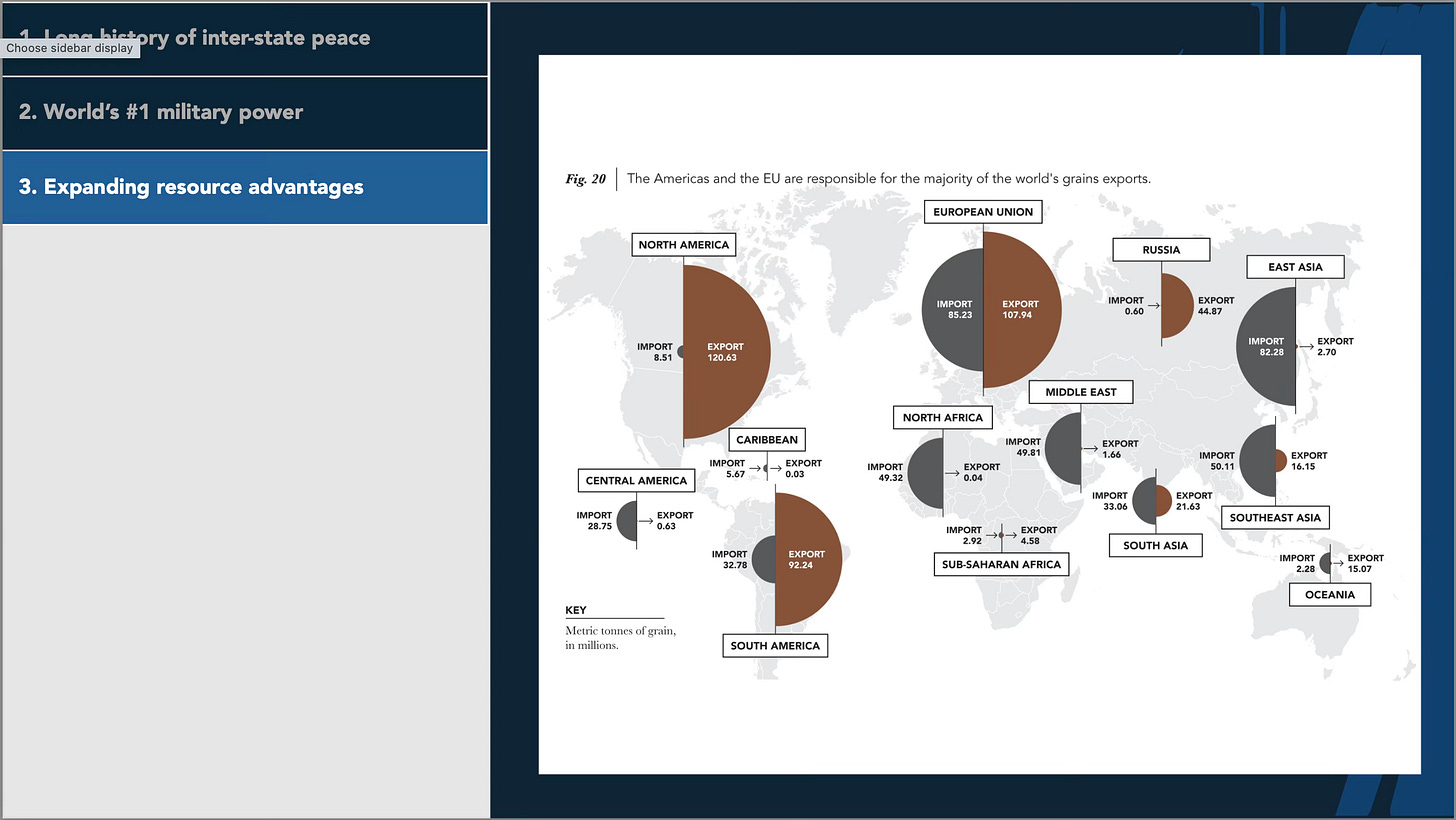

In terms of resource advantages, we are super-advantaged in water in South and North America, compared to the vulnerability in Asia.

That translates into an ability to export leftover food: there's what you grow, there's what you eat, there's what you import, and there's what's left over to export.

We are basically the Saudi Arabia of grain.

The West feeds the Rest: hugely important going forward.

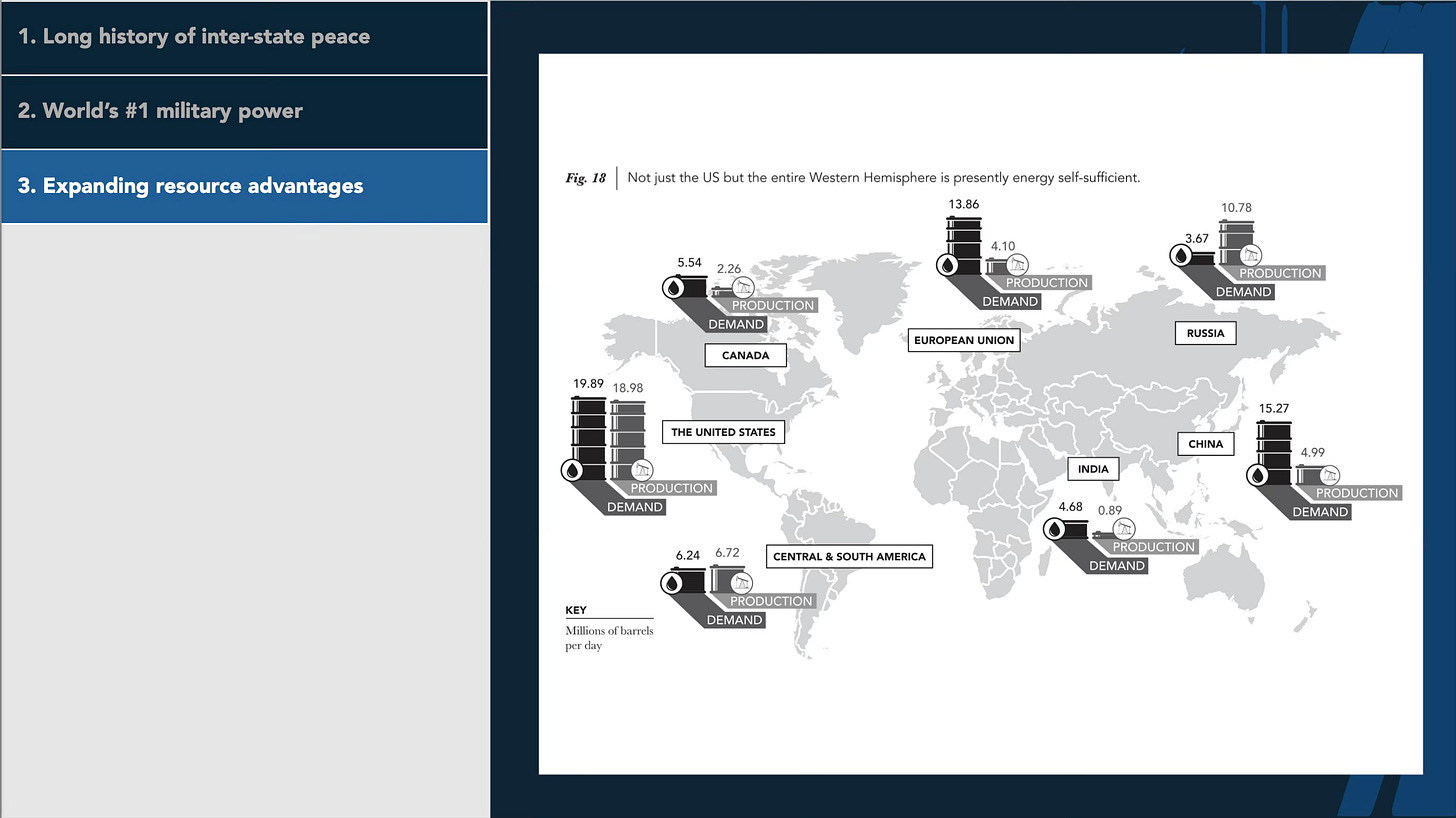

And then, in terms of energy, we're basically self-sufficient.

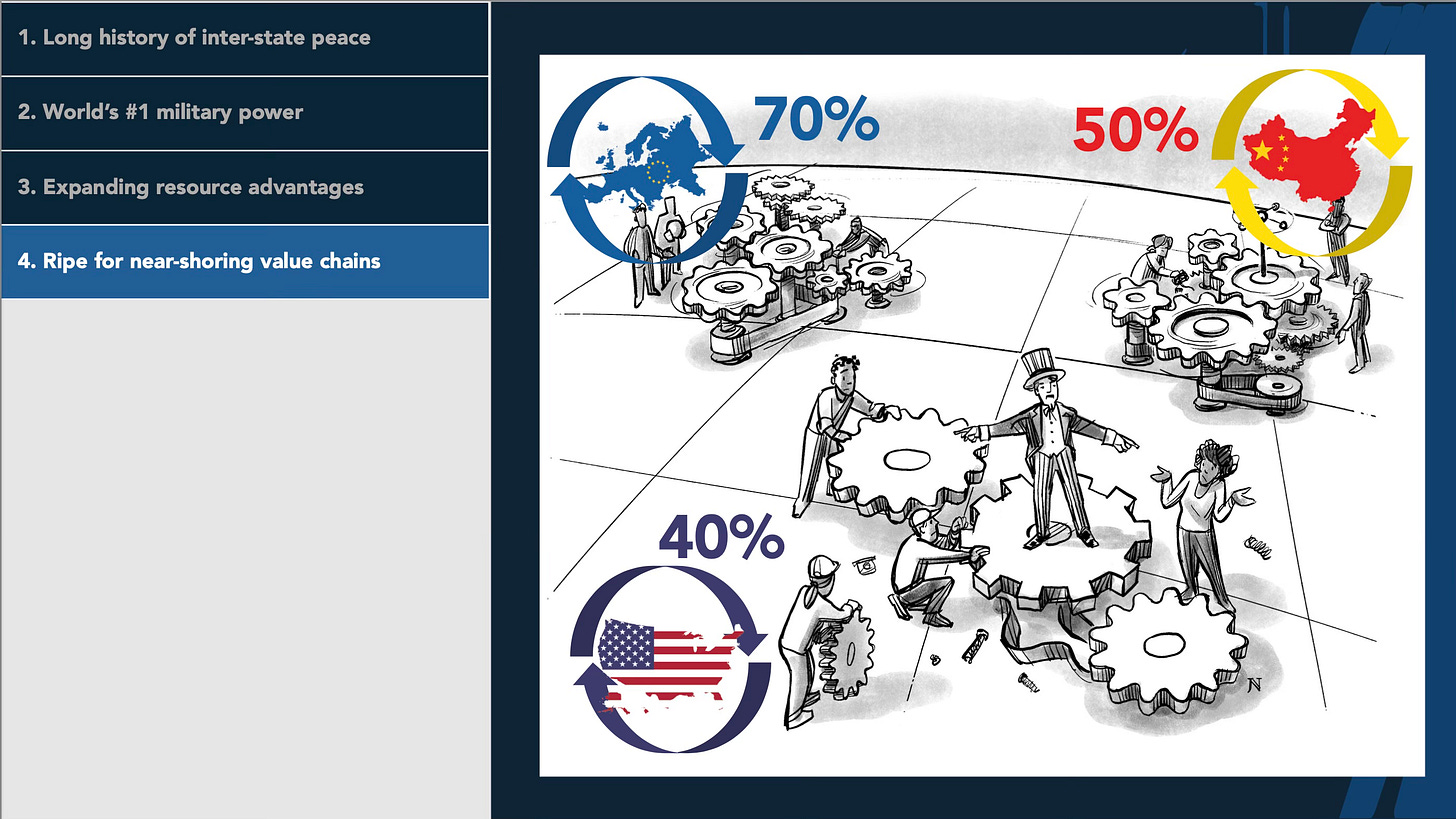

Some huge resource advantages in terms of reshoring/nearshoring value chains.

I will tell you the Europeans are far more integrated, as is Asia, than the United States, despite three decades of NAFTA, and our trade integration with Latin America is almost nonexistent.

Instead, we have a drug war -- it's just not exactly integration.

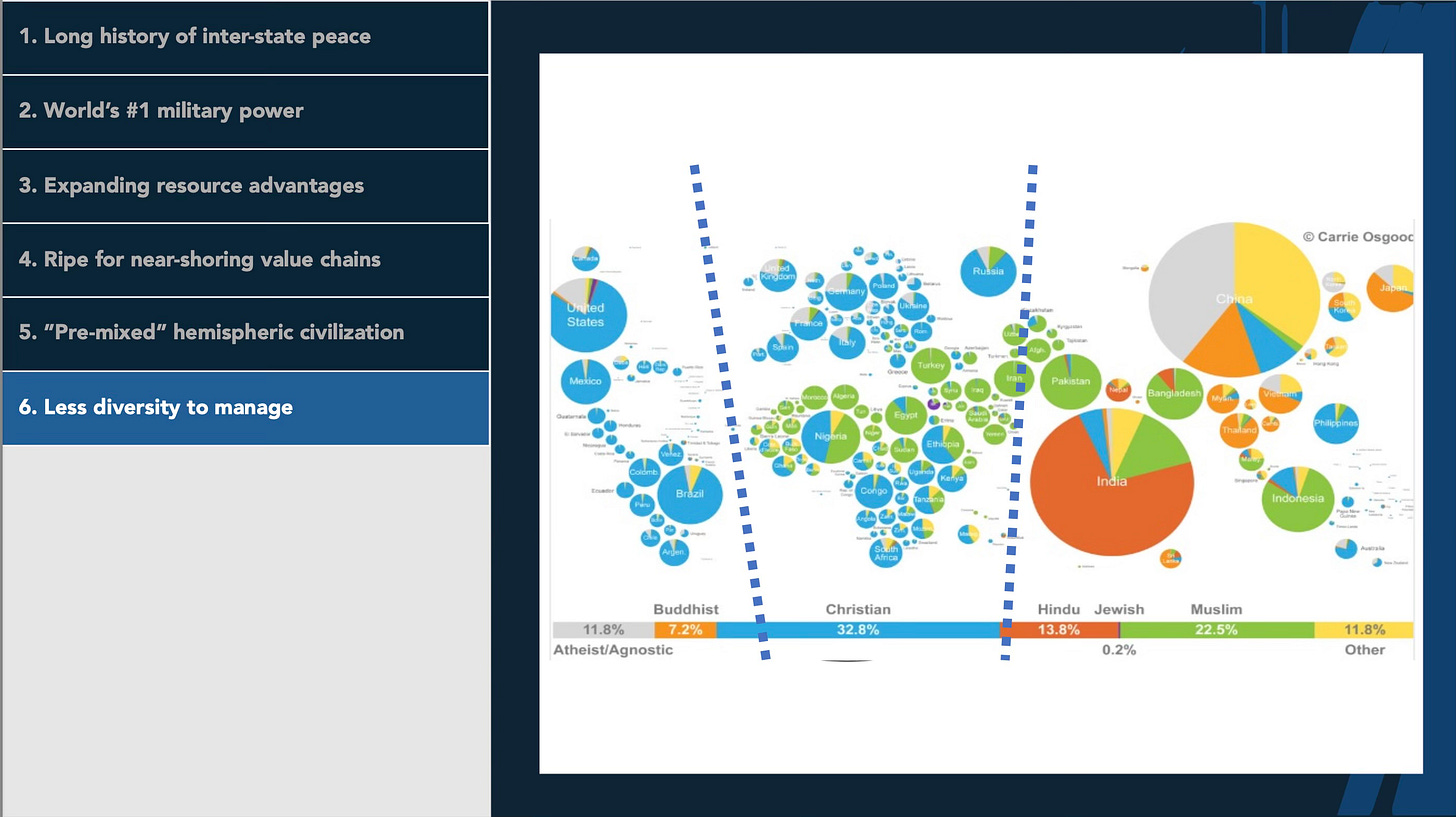

And then I'm going to make a more controversial argument here: I will tell you, on the basis of our experience on the receiving end of European colonialization, we have been mixing the major races around the world in the Western Hemisphere for half-a-millennia.

We are like the humans in The War of the Worlds: if the future is all about integration, we've earned the right to be good at that, because we've been doing it longer than anybody else in terms of diversity.

We have four languages, covers about 90%.

In terms of religious diversity, it's absolutely amazing: we are 80% Christian in the West, 60% Catholic.

You got Muslim versus Christian in the middle.

You’ve got a panoply of complexity in East Asia.

When we look North, because things are heading north, we luck out: we have the Canadians, who are the best, and they got the Russians, frankly, the worst.

Think about the Arctic council: watch that because China's gonna buy its seat on the Arctic Council soon enough.

I'd like to remind you, we were smart and bought ours in 1867, which was really farsighted.

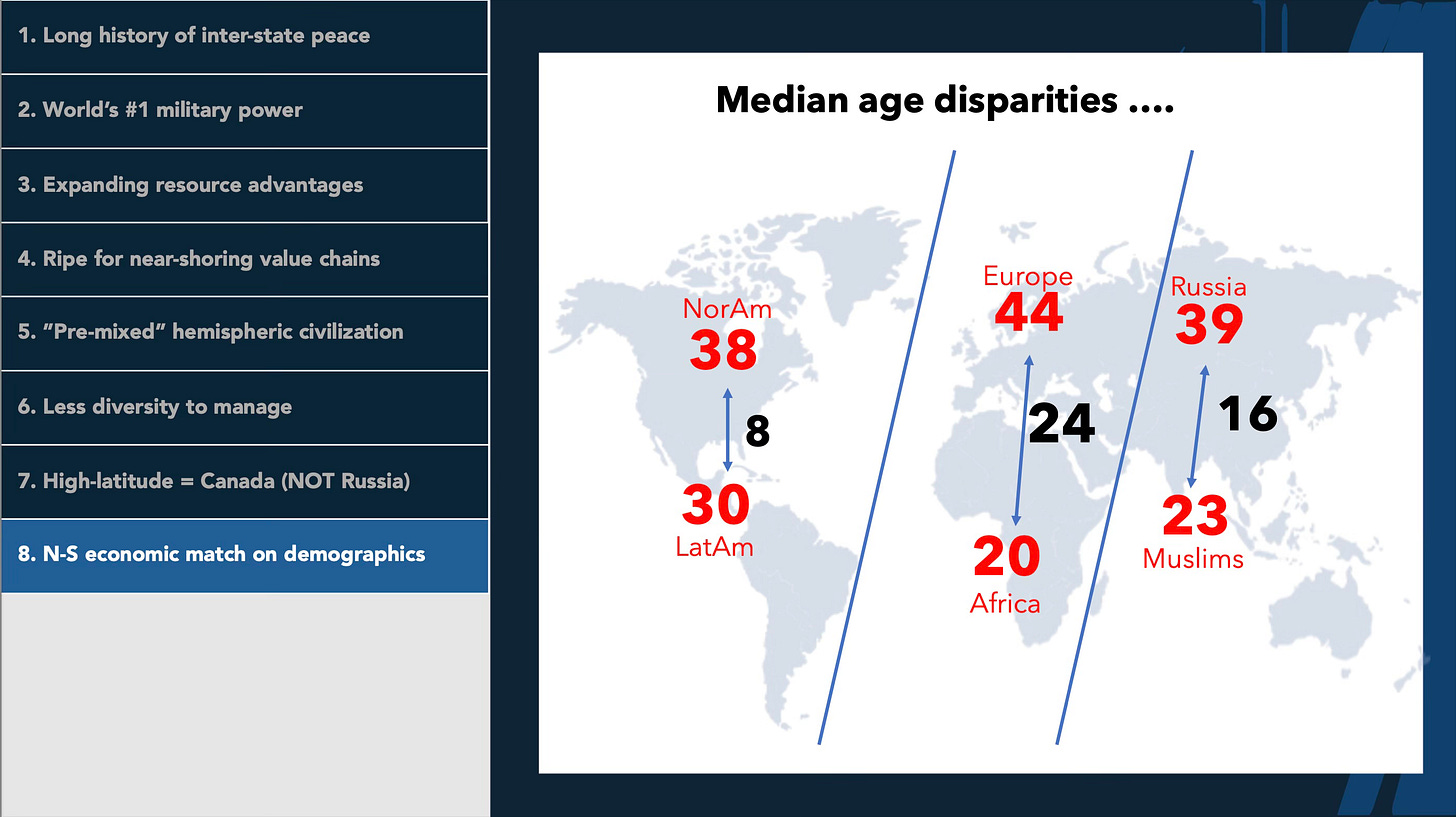

In terms of age disparities: much bigger gaps, the other part of the world; much more age appropriate in our part of the world – just enough to keep our age down as we get large-scale immigration.

In terms of democracy-versus-autocracy, it's amazing how uniform we are in the Western Hemisphere.

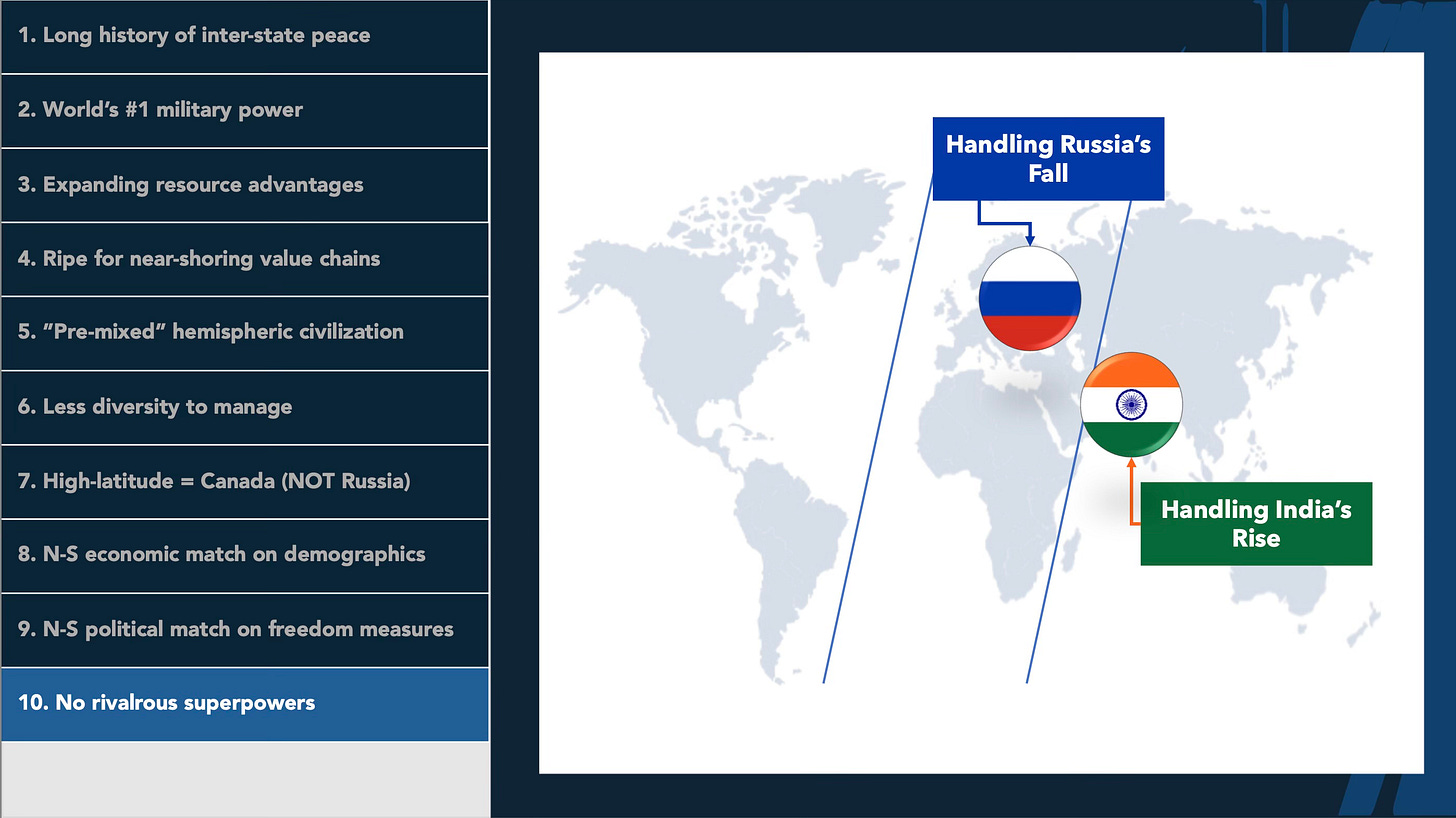

In terms of handling rivals with superpower relationships: we don't have to deal with India's rise like China does; we don't have to deal with Russia's fall like the EU does.

And then finally we have a whole section of the book on this: sort of my love letter to America.

There are wonderful things about our culture; we are admired.

If the walls came down tomorrow, we'd have a lot more citizenry.

But I don't want you to think along the lines of let's-let-them-all-in.

I'm not going to make the argument Matthew Yglesias made with One Billion Americans: let's increase fertility.

I don't believe you can do that, okay, I think it's a scary process to try.

And I don't think we want a billion people crammed into our country, but when I talk rethinking the relationship hemispherically, I'd like to extend the US borders; I'd like to offer membership tracks to countries, because when I look at a Honduras or Costa Rica in the future, I see nothing in this future that says, you know what, guys, you're on your own, this is going to work out.

Instead I see them reaching for that kind of connectivity, okay.

We started as 13 colonies, we're at 50 member states, 574 sovereign tribal nations, 14 territories, and a federal district.

We have tiered citizenship, tiered membership, tiered everything.

We have a history of doing this.

If the Europeans could do it, we can do it as well, for the same reason Europe went into Eastern Europe to deal with the problems preemptively.

I'm making a similar argument in terms of rethinking our relationship with Latin America.

Last point: this is where you get kind of brutally realistic with what we can actually do as a nation.

Are you under the impression that the US is going to out integrate China in East Asia?

Okay, we try, we offer defense pacts, we offer submarines to the Australians.

I don't think any of it is going to matter.

Can we out integrate the EU and Europe, deal with Russia more or better than they are now?

We could certainly help, we could be the arsenal of democracy.

They got their act together, by and large.

Current European Commission von der Leyen: she says, “We're basically a geopolitical union now,” and she's right.

That's how they've matured.

Do you think we're going back to the Middle East and taking over again in our lifetimes?

What our failures there did was activate all the regional kingpins to step in big-time, including the Chinese and the Indians.

Do you think we're gonna make the difference in terms of integration throughout sub-Saharan Africa?

I don't think.

So, I think the Gulf monarchies, I think the Indians, I think the Europeans, I think the Chinese are going to do that.

The one part of the world where it makes sense for us to integrate, where we have all the advantages, all the incentives, is our own neck of the woods.

That is a drastic rethink about how we deal with Latin America, the Caribbean, and with the Canadians.

It's very different, but if you want to build a better future, if you want something that Gen Z and Millennials are going to find worth constructing, I'm going to tell you, another five or six decades of Cold War with China … they're not interested.

They're not interested in the culture wars we're waging; they are deeply interested in climate change, getting ready for it, and getting ready for it, in my mind, is thinking North-South in terms of integration.

So, I'll be happy to take your questions.

Deloitte Host:

Dr. Bennett, thank you so much for those remarks.

To all of those of you in the audience, you can see the code there to submit your questions through menti.com, and we do have one to get us started:

Dr. Barnett, earlier this year, in April, India became the world's most populous country.

How do you foresee this impacting the global economy and the players in the globalization throughline?

Barnett:

Yeah, as I mentioned in the brief, you know, how you get to the top typically is tied into how well you exploit your demographic dividend.

China [Meant to say “India”] is coming online, big time.

Okay, in terms of a vast pool: about half a billion workers, okay?

Now, they are still at a very agriculturally-centric workforce, about 45% of workers in India deal in the agricultural trade.

So, how they make that transition is going to require, I would argue, lots of foreign direct investment.

We've seen their foreign direct investment take off dramatically.

They have to get a lot of that, I would argue, from the biggest saver in the system the last three decades – the Chinese.

The Chinese are incentivized to make sure that that demographic dividend gets exploited, but there's such a rivalrous relationship between the two.

That is going to be the most delicate relationship to manage over the next three to four or five decades, but the clock is ticking.

The Chinese already know they're on a path towards depopulation.

If they're not trading up in terms of moving up the production chain, in the value chain, and sliding in their replacement, then they're not succeeding.

So we need this relationship to work and I think the sign that India just surpassed the Chinese on that scale really tells us that the clock is ticking.

And, you know, I beg us to kind-of put aside our usual self-centeredness and not believe this is all about us versus the Chinese.

The fate that lies ahead, which is, we need India to integrate in a big way, we need them succeed.

If they do, the global economy is that much greater.

The fact that they're going to experience tremendous amounts of stress in terms of climate only suggests that another big engine in terms of global economic growth is going to be the green transition.

Next question.

Deloitte Host:

Sir, you have written this book with an eye on the next generation of leaders, namely the Millennials, the Gen Zs, and the Gen Alphas.

What's your most fervent hope or advice for them?

Barnett:

My most fervent hope, I think, they're already starting to express, you know, the Greta Thunbergs of the world, those Montana teenagers that sued over the environmental clause in the state constitution.

I mean, they're mad as hell about the lack of interest among the elite in America right now, the ruling class.

Congress is about 85%, I think, Boomers and Gen Xers, neither of them seem very interested in this process, and we're going to get this kind of review on the book all the time.

I've already got a couple of them, where you get a 69-year-old white guy basically saying, “Hey, I'm not going to live in this future; I don't really care, okay?”

And all I can say to that is, you know, there's the door, Boomer, and thank you for your contribution to US National Security.

Because the people who are going to get stuck with it are my two millennials and my four Gen Zs, and they're waiting and they're getting more agitated.

We saw it with the Republican presidential debate – the first one: First question, they had a young kid, you know, millennial: “What do you care about?

And he got up and he held the microphone to his mouth and he said, “Climate change, what do you got?”

And all eight or nine candidates basically stared at their shoes and Ramaswamy yelled out “Hoax!”

And that was the response, you know.

I don't credit the Democrats, really, all that much more than I blame the Republicans on that one.

I think both sides, you know, as much as I like what Biden has done in terms of trying to deal with climate change in terms of prioritized spending, we are nowhere near the thinking and the action that we need to be on and, if we were, this would be a presidency that we've been waiting for, for quite some time: we've been promised this presidency over and over and over again – “I'm going to care more about Latin America, I'm going to fix our relationship with our neighbors, we're going to have a better time in there, in the atmosphere.”

That hasn't happened.

It gets promised every election cycle, and what I would tell them to do is just break the mold where you can, and the quickest way to break the mold on this thing, I would argue, is the 51st state – however achieved.

So, Puerto Rico would be the 30th largest-by-population state overnight.

DC certainly qualifies.

There are other packages we could put together.

We've done non-contiguous before: Hawaii and Alaska.

We've done monarchies, we've bought stuff just plain out, okay?

Anything that would break the mold would raise the question, “If they can get in, who else is possible, where else could we have this discussion?”

To me, this would be the ultimate trump card – no pun intended: offering an accession track just like the Europeans do, so that when any of those countries are dealing with outside superpowers, they can always say, “You know, well I've got sort of this outstanding offer from the United states, it'll take 5-to-10 years, it's a hell of a journey, but if that's what you're offering maybe I should go with the Americans.”

That alone would be an execution of soft-power resources, a whole of government kind of response that we don't have now right now.

We offer defense pacts and sanctions: you're either with us or against us – that's our offering.

The Chinese are offering something bigger, the Europeans are offering something bigger – geopolitics of belonging.

We need to think along those lines, I think.

Future leaders, Millennials and Gen Zs, are going to be a lot more interested in that kind of pathway, dealing with climate change, on that basis socializing that risk that we already see coming across the border daily, you know, the dry corridor, the northern triangle mega-drought for years and years now.

That's where the Guatemalans, El Salvadorans, Hondurans, they're all coming on the basis of that kind of stress – environmental.

We think they're coming because of MS13 in the city.

You got to ask yourselves, Why are they in the city? Why did they leave the land, okay?

That's the kind of problems that we need to deal with, and anything that moves it along, that line breaks the mold, breaks the thinking, gets the conversation shifted, I think would be absolutely fantastic.

Deloitte Host:

We've had so many fabulous questions submitted, but to close this out on our last one for the evening, before we break:

How does your proposed grand strategy align with traditional US grand strategy of offshore balancing?

Barnett:

I think it does, in the sense that offshore balancing, you know, we got into this superpower game after the Second World War, we decided to kind-of box in the Soviets left and right and salvage what we could on both sides, okay.

Then we got very focused on the Middle East over the course of the Cold War, okay.

So we've done the entire Eurasian landmass left, right, and center.

I think we can remain an offshore balancer.

I think the glue argument, that Pacific command offers regarding our military presence throughout the Pacific, has worked.

The first time in human history, we've got a number of powers that have risen without war and we've changed the global economy on that basis.

So, I'd like to see us continue that role.

Do I think it has to be a lot more unmanned?

Yeah, I do.

I've been making that argument for 20 years, so I think there are ways to adjust to this.

What I'm describing in terms of an integration focus southward is not, say, DoD.

It's more like Homeland Security; it's more like a true whole-of-government response.

One victory, I just saw recently, that I thought was just amazing, I thought, that's what I'm looking for, was Amazon Web Services signs a deal with El Salvador, the new young president, to do all their government services in the cloud for the next seven years, okay?

Now, Huawei comes in and does that, we're pretty scared about it.

When Amazon comes in, that feels pretty good, okay, so that kind of reality, thinking along those lines, less combative with our tech giants, I'd like to see us more eagerly push that kind of connectivity.

And, you know, it's not so much the Monroe Doctrine I'm looking to reinstall.

I don't want to get in a tit-for-tat fight with the Chinese and the Russians and the Iranians kicked out of places.

I want to offer a better connectivity package, so I think more along the lines of the Roosevelt Corollary: I want to keep you out of debt-trap diplomacy, which we've already seen the Ecuadorians kind of fall into.

That's the limit of the Chinese model: there is no joining the Chinese Dream; there is no joining the Chinese union.

Anybody can become American, any part of the world could become American, okay?

We have the brand that is the power.

It's not our money; it's not going to get it done because we don't have that much, and there are limits to what we can do with military power.

But the attraction of our brand is immense and I'd like to see that, you know, weaponized, turned on, turned into something better, because, as I argue with that zone of turbulence, next 20, 30, 40, 50 years, between climate change, demography, the demands of a global middle class, there's no way America is going to be the biggest power in the world unless we adapt –radically.

Okay, scientists tell us that species have to adapt 10,000 times their normal evolutionary rate.

OK, if that's happening in the natural world, then certainly we've got to pick up the pace in the political and economic realm.

I think we have the capacity with AI and everything else coming on.

I think we have the technology, we have to stop demonizing scientists and science.

We have to embrace our capacity to deal with complexity and we have to make this offer, not because we want to take over Latin America, because we want to offer them something better, and I think it's about time that we engage in that kind of empathy on a hemispheric basis, because we're all living together in this world.

Deloitte Host:

Thank you so much.

Appreciate your remarks.

For our guests, we invite you to move to the other portion of the room.

There will be books available for sale.

Dr. Barnett will be available for signing and there are some refreshments, so thank you so much for your time, Dr. Barnett.

Thank you very much for this and the past 25 years.