The Extinction Countdown: How Many Species Will be Lost to Climate Change?

A special series of newsletters leading up to my 1 May open online presentation

BLUF

Bottom line up front: about three-quarters of the world’s species are disappearing in this current mass extinction era.

Nature’s three-card monty (place your bets)

As I like to remind, climate change offers all species the same three doors to choose from:

The first option (adapt) is extremely hard, with those best adapting being our least favorite species. From America’s New Map:

Thousands of studies indicate that most species, while furiously adapting, still fall behind the climate change curve. Shifting the timing of key biological processes (e.g., salmon showing up earlier to spawn) is one thing, while changing morphology (body characteristics) or diet is far more difficult. In general, species smaller in size, with shorter life spans and higher-frequency procreation, adapt better than larger, longer-lived species.

That means climate change is an evolutionary boon for parasites and pathogens—vectors of human disease.

The second option (move) is the very definition of climate velocity:

“Climate velocity describes the speed and direction that a species at a given point in space would need to move to remain within its climatic niche”

(Loarie, S. R., Duffy, P. B., Hamilton, H., Asner, G. P., Field, C. B., & Ackerly, D. D. (2009). The velocity of climate change. Nature, 462(7276), 1052–1055. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08649)

The climate moves, and you as a species simply move with it or suffer the consequences.

Below is an animated map of such migrations, found online here.

Which leaves us the third option (die) — failure leading to extinction.

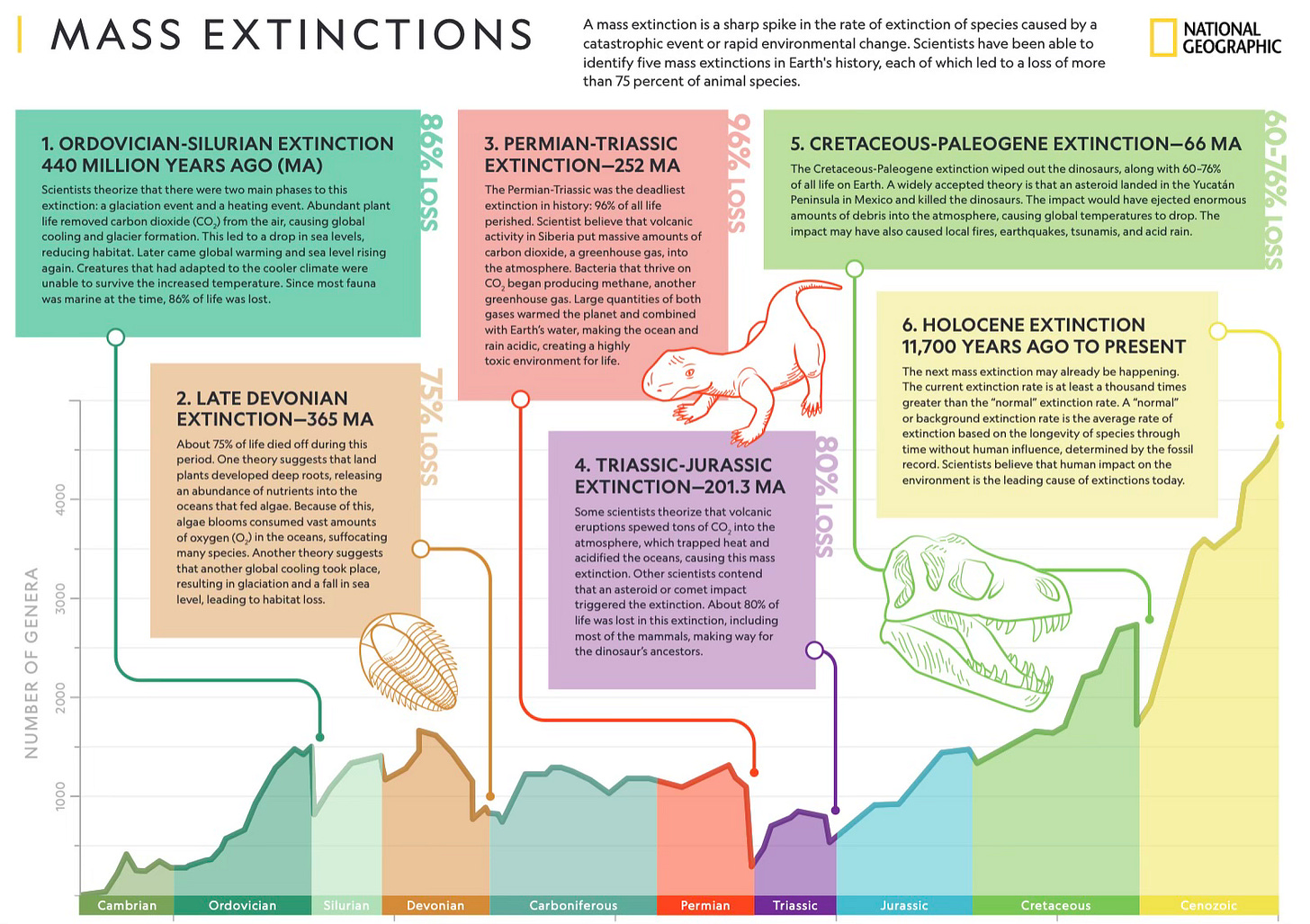

How bad is the current mass extinction era compared to previous ones?

There have been a number of mass extinction periods in Earth’s history:

Our present one, still dubbed above as the Holocene Extinction (eschewing the widespread move to calling our current geologic era the Anthropocene or Human Epoch) is, by all accounts, rapidly unfolding (1,000 times the normal extinction rate). How far the resulting dip in genera goes is not yet apparent on this chart due to the extremely long timeline displayed here, but we are looking at the definitional threshold being reach — namely, a 75% or higher loss.

What are the primary causes of the current mass extinction era?

From the World Wildlife Fund, how this era of extinction is so different from previous ones:

Unlike previous extinction events caused by natural phenomena, the sixth mass extinction is driven by human activity, primarily (though not limited to) the unsustainable use of land, water and energy use, and climate change. Currently, 40% of all land has been converted for food production. Agriculture is also responsible for 90% of global deforestation and accounts for 70% of the planet’s freshwater use, devastating the species that inhabit those places by significantly altering their habitats. It’s evident that where and how food is produced is one of the biggest human-caused threats to species extinction and our ecosystems.

So as to avoid laying all blame at the feet of the farmer who feeds us, a more broadly framed perspective cites three main causes, all of which are considered human-caused or anthropogenic:

Overhunting and overharvesting by humans (think of the American buffalo, or fisheries fished to the point of collapse)

Invasive species piggybacking on human-constructed transportation networks or associated with climate velocity triggered by human-caused global warming (so, even the move option contributes to more species loss in a double whammy)

Loss of habitat — basically the farming issue cited above, plus mining of natural resources and urbanization.

How can that loss of biodiversity come back to haunt humans?

There is a negative feedback loop here: loss of biodiversity in the natural world dovetails with humanity’s narrowing down of its agricultural production to just a few lead crops — the associated danger of monoculturalism.

Go back and watch Christoper Nolan’s Interstellar, because that very scenario (dust bowl-like soil degradation, monoculture crop failures, etc.) is the fundamental driver of why humans need to leave Earth and seek out planets suitable for colonization (the imagined variant of California’s role as safe haven during the Dust Bowl era).

Along that dangerous path, for example, in America: long ago our ag sector was highly diversified, but now it grows corn, soybeans, and wheat to a stunningly concentrated degree (estimated at 90% of the planted acreage as of late), meaning, if the right crop killer comes along (e.g., blights triggered by fungus — so very The Last of Us), we’ll be in a world of trouble because we’ve so biologically narrowed that all-important sector.

In short, the current mass extinction crisis reduces agricultural biodiversity, disrupts supporting ecosystems, and compounds the dangers of the industrialized, globalized, and monocultural model of modern agriculture.

The geopolitical consequences are real

Everything I’m describing here is unfolding around the entire planet. Due to climate change’s harshening impact on the lower latitudes (my concept of Middle Earth stretching 30 degrees north and south of the equator), rising powers like China and India will lose big on farmland/production, while vast, empty Russia, along with Canada, conceivably become tempting targets for a take-over: as in, sovereign velocity matching climate velocity.

Inconceivable from today’s perspective, but less so amidst a global food crunch sometime later this century.

Understand, how climate change and its impact on biodiversity plays out globally in agriculture will greatly determine food security in the future, as a handful of regions produce the handful of grains that account for the majority of calories consumed by humanity today (as corn, rice, and wheat combine to provide just over half of humanity’s caloric intake all by themselves).

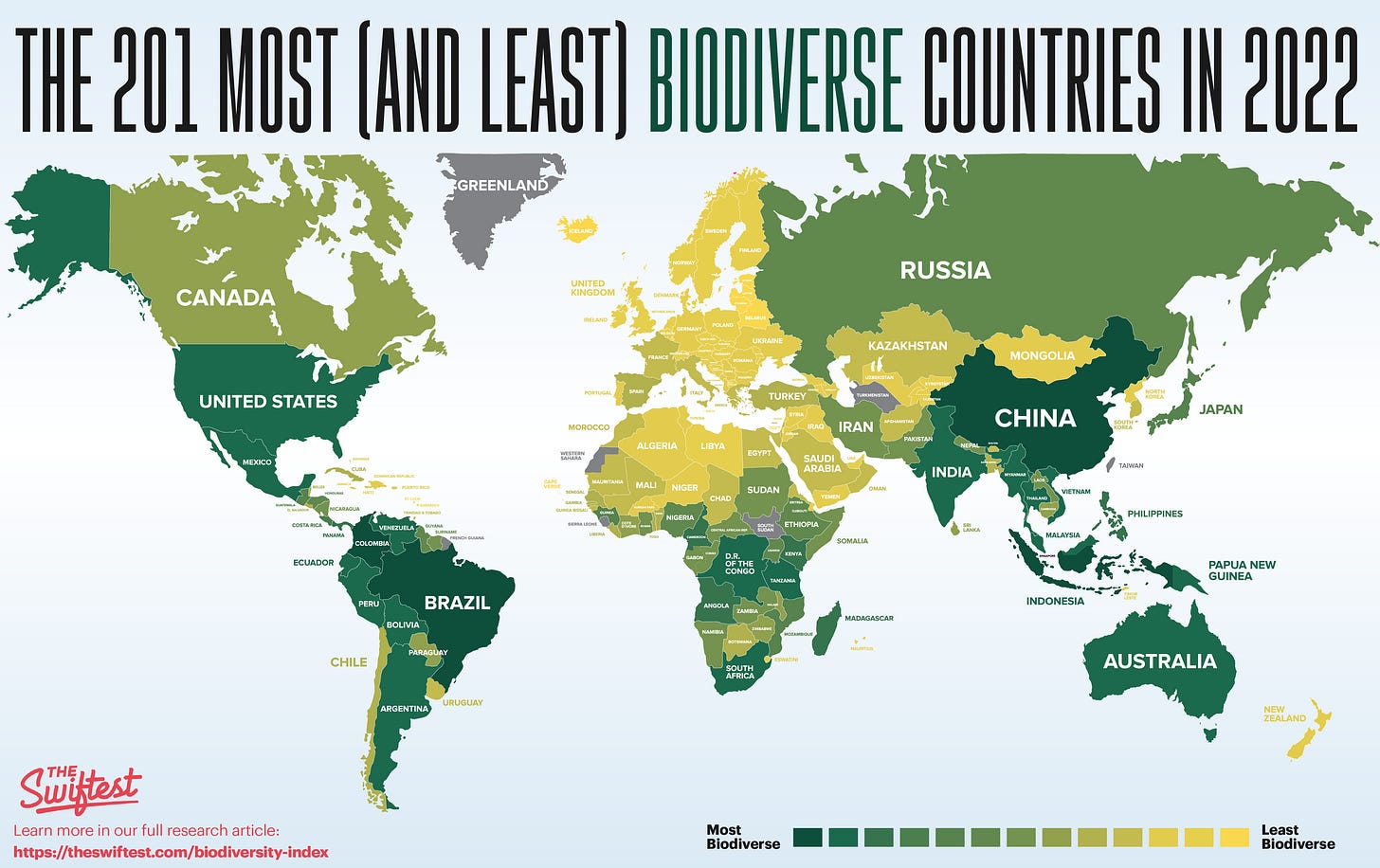

The singular role played by the true West amidst declining biodiversity

This handful of regions presently provides the bulk of those grains left available for export, with the Western Hemisphere largely feeding the food-insecure Eastern Hemisphere. Remember: there’s what you grow, what you import, what you eat, and what’s left over for export. The Western Hemisphere has a lot left over; the Eastern Hemisphere, little-to-none relative to overall need.

So, if you knock out the North American agricultural sector, like Christopher Nolan scenario-ized in Interstellar, then the world is suddenly plunged into some serious danger.

This is why Eastern powers (China, Japan, South Korea, Persian Gulf monarchies, etc.) are buying up farmland across the world. It’s also why US states are banning Chinese purchases of farmland here in America, where up to 3% of all farmland is presently owned by foreign entities (roughly the equivalent of Iowa’s planted acreage). Global corporations are also highly active in securing ownership of arable land, understanding that the further away from the equator it lies, the better the odds it will remain arable in the decades ahead (my previous post about climate velocity).

Biodiversity = food security?

The Western Hemisphere has a strong biodiversity across the bulk of its combined landmass, befitting its tremendous capacity for grain exports to the East, where large, biodiverse Russia is the primary grain exporter of note (along with Ukraine).

This geopolitical reality reflects the typically positive relationship between biodiversity and food security — so long as you carefully manage and preserve both. Both the Americas and East Asia are biodiverse, but the population pressures in East Asia have rendered it quite food insecure.

How all this rises to the level of American grand strategy

Grand strategy is how a country uses all its assets and capabilities to achieve long-term goals.

What I argue in America’s New Map is that climate change and its growing impacts on the world have clearly risen to such a level of importance to US strategic interests that it only makes sense that Washington have a grand strategic vision and approach for dealing with it across this century.

Moreover, I argue that the approach we undertake should focus on North-South integration across the Western Hemisphere — in effect, to consolidate the incredible advantages we collectively possess in relation to the challenges posed by both climate change and demographic aging.

Finally, I argue that such a grand strategic focus on hemispheric integration is our best competitive approach to the geopolitical challenge posed by China, which, if we’re not active in this regard, will pull Latin America and the Caribbean inexorably into its economic and ideological orbit — leaving us to deal with any resulting immigration pressures triggered by Beijing beggaring our neighbors in its quest for resource, energy, and food security.

If I’ve successfully made that sale to you …

Then please consider attending my online executive roundtable on 1 May at 5pm Eastern [contact Liz Gaither at lgaither@throughline.com to confirm].

Grand strategies cannot merely be imposed from on high. They require whole-of-nation buy-in and that begins with all of us. So, if you’re willing to engage this ambition with Throughline and I, then I’ll be happy to see you on the 1st for my briefing and discussion.

Sign up to take the America’s New Map MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) at edX