When I was in Syracuse last month for my regular lecture there, I was told the story of how the town won this big new semiconductor plant that is going to create thousands of well-paying jobs:

Micron wins $6.1 billion CHIPS grant for Central NY and Idaho projects, Schumer says

So what — besides having Chuck Schumer in your corner — enables the Syracuse area to win this great development?

It all comes down to water and power being co-located.

Upstate New York has the water alright, and it can tap into both strong local power generation and, if need be, Canada’s strong energy grid just across the border (Canada sells a lot of its hydropower southward to us, but especially to that general New England area, which relies on Canadian hydropower for a huge portion of its electricity).

Note also that, if and when Canada goes dry from climate change impacts, like it recently did, that energy flow can and must be reversed;

Abnormally Dry Canada Taps U.S. Energy, Reversing Usual Flow: Lower-than-normal rain and snow have reduced Canada’s hydropower production, raising worries in the industry about the effects of climate change.

The new Syracuse-area factory will be located less than 30 miles from Lake Ontario, slated as the primary water source for the plant. Micron needs up to 48 million gallons of water per day when fully operational. This big-time water requirement stems from the water-intensive nature of semiconductor manufacturing, which involves frequent washing of chips to remove chemicals.

Lots of rinse and repeat.

The second piece of the puzzle? The site will be wired up to a robust regional electrical infrastructure, drawing power from local hydroelectric and nuclear plants, rendering the energy supply both reliable and renewable. This facility's energy consumption is projected to exceed the combined usage of Vermont and New Hampshire (!), giving you a sense of the scale of Micron's operations.

Water plus power — the key nexus going forward.

Now pull back our lens to encompass the Western Hemisphere: 13% of humanity living on 45% of the freshwater while being, for all intents and purposes, energy independent as far as the rest of the world is concerned (we don’t need their energy, but yeah, they need our food).

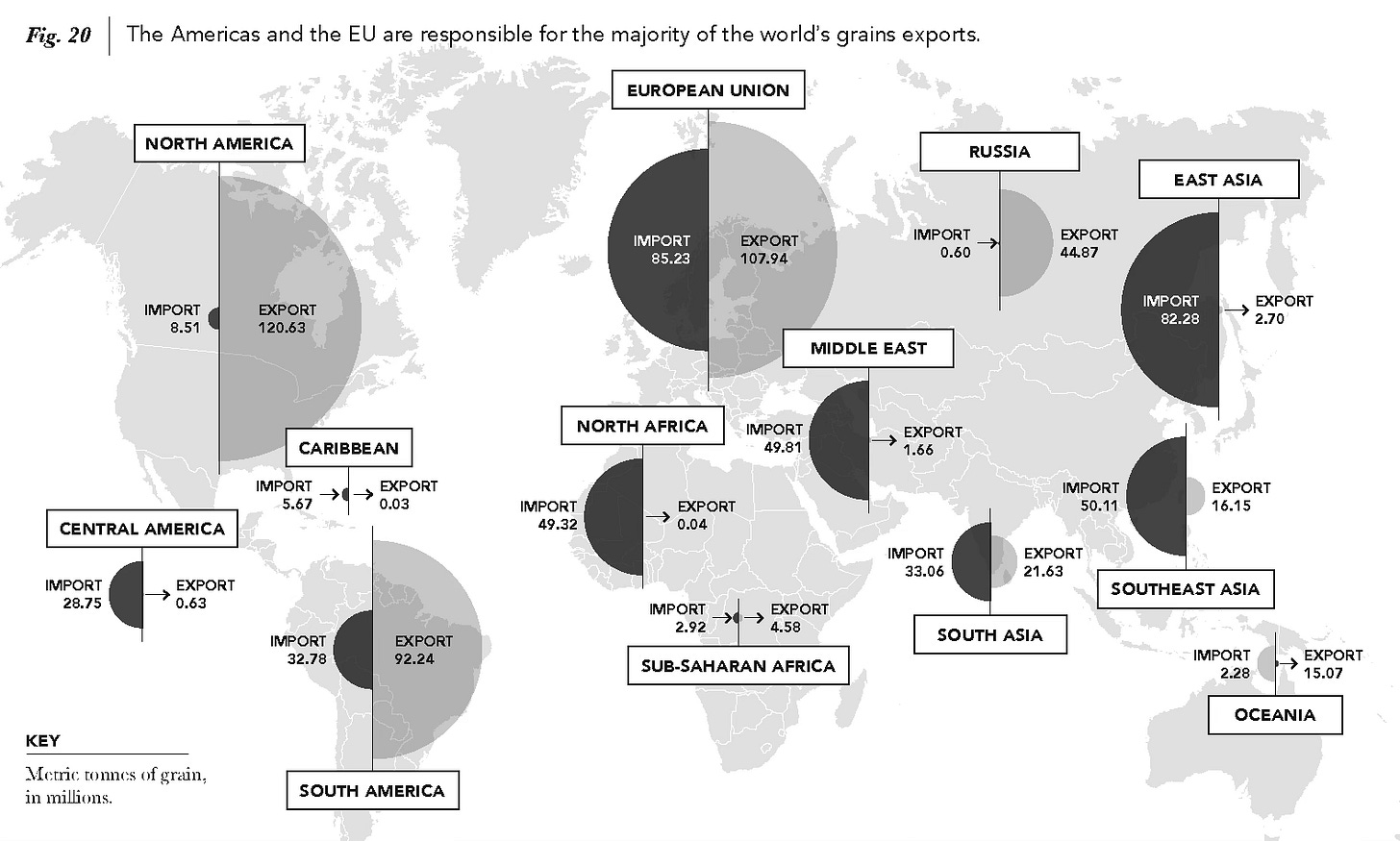

One could say that the primary way we in the West presently monetize that water + energy advantage is in turning it into food that we export. This is the fundamental reason why the West is able to feed the Rest (covering their enduring and large and growing shortfall in food production).

Are we terribly organized about this? Not really. Certainly not in a hemispheric sense.

Have we ever really tried to organize ourselves on this score?

Check out the North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA, pronounced nu-WAP-ah), an imagining of some far-sighted thinkers back in the 1950s. From Wikipedia:

The North American Water and Power Alliance(NAWPA or NAWAPA, also referred to as NAWAPTA from proposed governing body the North American Water and Power Treaty Authority) was a proposed continental water management scheme conceived in the 1950s by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The planners envisioned diverting water from some rivers in Alaska south through Canada via the Rocky Mountain Trench and other routes to the US and would involve 369 separate construction projects. The water would enter the US in northern Montana. There it would be diverted to the headwaters of rivers such as the Colorado River and the Yellowstone River. Implementation of NAWAPA has not been seriously considered since the 1970s, due to the array of environmental, economic and diplomatic issues raised by the proposal.[1][2] Western historian William deBuys wrote that "NAWAPA died a victim of its own grandiosity."[2]

The plan

A technical and economic blueprint for the plan was developed in 1964 by the Parsons Corporation of Pasadena, California.[3] The total cost was estimated in 1975 as $100 billion, comparable in cost to the Interstate Highway System.[4][5]

Water management

The Parsons plan would divert water from the Yukon, Liard and Peace River systems into the southern half of the Rocky Mountain Trench which would be dammed into a massive, 500 mi (805 km)-long reservoir. Some of the water would be sent east across central Canada to form a navigable waterway connecting Alberta to the Great Lakes with the additional benefit of stabilizing the Great Lakes' water level. The rest of the water would enter the United States in northern Montana, providing additional flow to the Columbia and Missouri–Mississippiriver systems, and would be pumped over the Rocky Mountains via the Sawtooth Lifts in Idaho. From there, it would run south via aqueducts to the Colorado River and Rio Grande systems. Some of this water would be sent around the southern end of the Rockies in New Mexico and pumped north to the High Plains, stabilizing the Ogallala Aquifer. The increased flow of the Colorado River, meanwhile, would enter Mexico, allowing for greater development of agriculture in Baja California and Sonora.[1][6]

The project would provide 75 million acre-feet (93 km3) of water to water-deficient areas in the North American continent,[7] including Canada and the United States, as well as irrigation water for Mexico, which Parsons claimed would receive enough water to reclaim 7 or 8 times more land than Egypt reclaimed with the Aswan High Dam.[8] It would provide increased water flow in the upper Missouri and Mississippi rivers during periods of low flow, increased hydropower generation along the Columbia River, and stabilize water levels in the Great Lakes.[9] Parsons originally proposed using peaceful nuclear explosions to excavate trenches and underground water storage reservoirs for the system.[10]

Power generation

The project would generate a vast amount of electricity from a number of hydroelectric and nuclear powerfacilities (the latter of which would be required to power the multiple pumping stations needed to move the water across the continent).[1] The issue of electricity generation created some controversy, with some commentators such as Marc Reisner arguing that the plan would be a net consumer of energy, while others estimated a net gain of 60 to 80 million kilowatts after meeting the needs for pumping.[7]

Transportation

The plan would potentially have included a navigable waterway in Canada from Alberta to Lake Superior, to be called the Transcontinental Canal. In addition to increasing availability of water, the canal would address problems of water pollution.[7]

Fascinating stuff, right?

The future, Mr. Rango, the future!

[And yes, I like Rango better than Chinatown as a movie reference here because of the latter’s creepy surprise.]

Now, consider the state of understanding on climate change back then … basically a toss-off line in the movie Soylent Green (planet warmed up, we can’t grow enough food, gotta eat “excess” people — or just the tastiest ones!). No real sense of danger or disruption. This is strictly an overpopulation problem, which environmentalists loved to emphasize back then.

So, in retrospect, a seemingly small problem to be solved by a grandiose, slightly crackpot scheme that, at that point, clearly lacked the IT strength and capacity to pull off.

Now, fast-forward to today, with Phoenix basically declaring itself closed for further development due to water constraints and mature (pun intended) Northern economies beginning to freak out about depopulation!

Now, it would seem, we have entered a time in which what was previously inconceivable is now not all that crazy.

I mean, we in the West have this huge and enduring advantage, so why wouldn’t we be doing everything conceivable to protect AND leverage it this century?

After all, is this not the century in which “water is the new oil”?

Then, let’s add in the high-tech requirements to marry water and power. Does it not seem like we should be thinking and planning and acting big on this vast challenge, given all our computing advances — as of late and today and tomorrow?

Think back to the 20th century and the Age of Oil: those places with great supplies but also great need quickly used up much of their reserves. Places with less need but plenty of supply? Well, eventually they got organized (OPEC) and started treating their energy reserves as a geopolitical asset almost without peer. Those states banked all those profits (petrodollars) and eventually became very big-time players in global investment and development (see the UAE as top provider for foreign direct investment for a dozen or more states across its growing global footprint).

Thus, those who had extra turned those assets into money and financial wherewithal and became very powerful within the world system on that basis.

Should we in the Western Hemisphere not do the same? Should we not be thinking along similarly ambitious, world-shaping lines?

Take just North America and that NAWAPA scheme: doesn’t it make great sense that, in a situation where Canada has too much and Mexico has too little, and America in-between is seeing large portions of its territory balancing these issues like a snail moving along the edge of a knife, we’d want to get super-organized and smart and high-tech on this entire package?

In this age of pervasive sensoring, the rise of AI and the IoT, and the stressing onset of climate change, isn’t it imperative that we look ahead, plan ahead, and organize, marketize, and financialize this future much like the old oil powers of the Middle East once did?

Or do we just pretend that we should leave it to local government? Or the states? Or maybe at the federal level? Or the public sector alone?

Climate velocity is making borders less and less … I dunno … meaningful. Humanity needs to keep pace by scoping its vision, ambitions, plans, and investments.

Otherwise, we will keep falling behind the curve that is climate change.