I have often told people that the trick of owning a home is about three-quarters defined as making water go away from your house successfully. You want the sinks and tubs and showers and various washers to all successfully empty out through your connection to the sewer system (or your septic). You want your house to be sufficiently dry of humidity. You want rain and snow melt to roll off your roof and move smartly away from your foundation. You want no leaking in any of these sub-systems, nor any blockage.

If you do all that successfully, then you are well on your way to success as a homeowner. It’s not everything, but it’s really the baseline thing: without success there, it is hard to achieve elsewhere — foundational in both a literal and figurative sense!

Throughout human history, sufficient access to, and successful management of water resources determine the emergence of civilizations and their subsequent sustainability/success, with the biggest and best successes coming to those who are truly tri-capable in potable water (for human drinking), non-potable water (other non-salt water usable for agriculture — the BIG water-sink, far trailed by industrial uses), and salt-water (mostly about access to oceans for transportation needs, oftentimes where the great rivers meet the sea).

Successful utilization of fresh water resources is good management of some combination of groundwater resources and those reservoirs (aquifers) located deeper underground.

Where all these meet with climate change: rising sea levels confronted by sinking shorelines as we empty out aquifers, leading to land settling downward.

As I noted in America’s New Map, those regions blessed with relatively solid access to freshwater resources (both in the water-cycle and those longer-term “fossil” water reserves that cannot be replaced on a human timescale) relative to their population size/load requirements are, in effect, water-rich.

One way to capture water-wealth versus water-need is to compare a region’s share of the world’s population against its share of the world’s freshwater resources, as we do in this data visualization from the book:

You look at this map and it’s pretty clear that the Western Hemisphere has a lot more water than people (bottle bigger than person), while the Eastern Hemisphere is, by and large, short on water (Australia/New Zealand being an outlier).

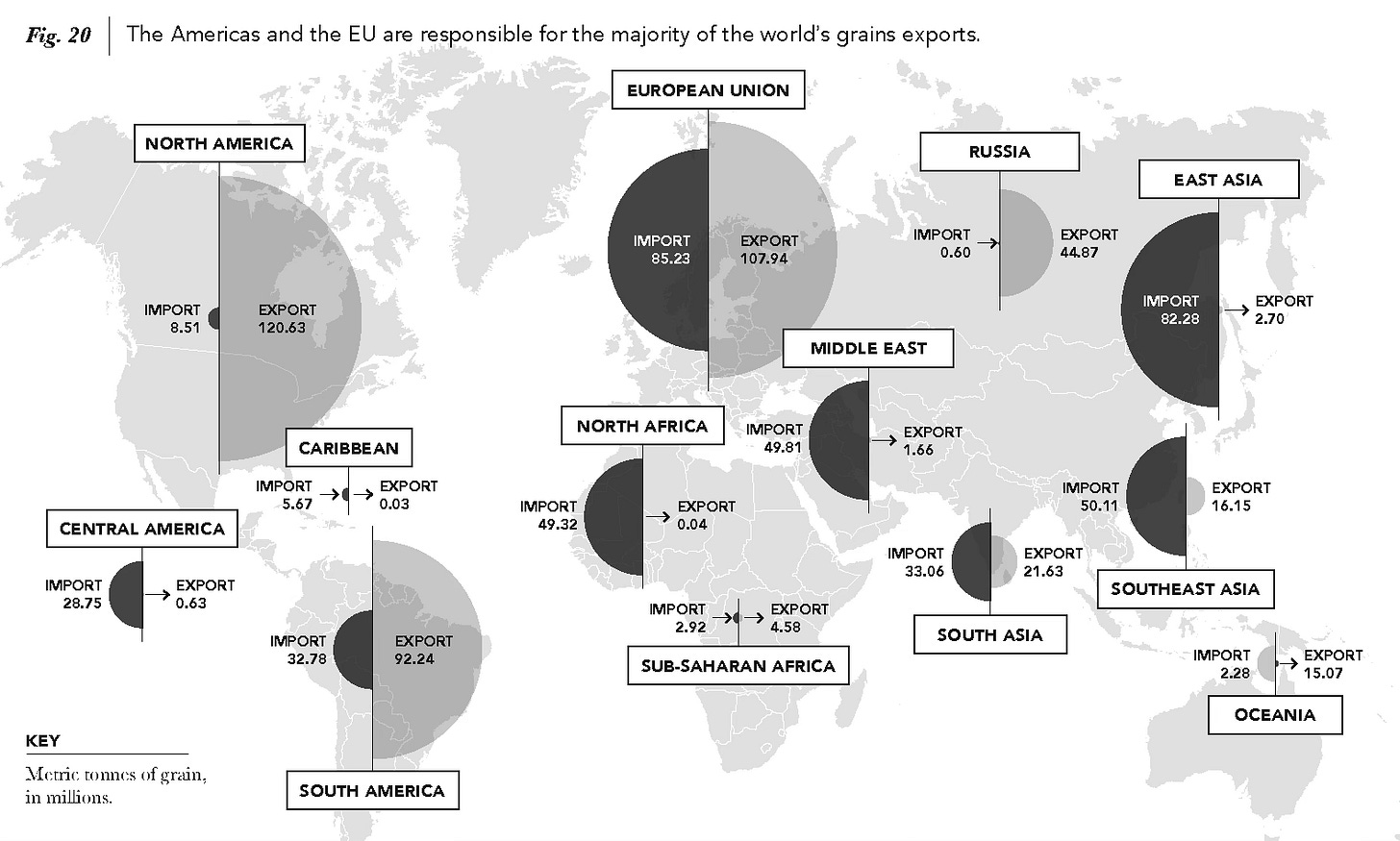

Unsurprisingly, having extra water-share relative to population-share means you can export food (the equation being: what you grow + what you import - what you eat = what you can export), as portrayed on this data visualization from the book concerning the major grains comprising almost two-thirds of humanity’s caloric intake:

You look at this map and you realize that an advantage in water equals an advantage in food exports — and vice versa on disadvantages. This generates my ANM observation that the West feeds the Rest — something one needs to keep in mind whenever proposing … say … a post-American world.

Food can thus be thought of as water turned into human energy-supplies that are thereupon more easily moved around the world than water itself can be.

In the realm of human needs, water (3 days hard limit) ranks just below air (3 minutes hard limit) and way above food (3 weeks-3 months [extreme] hard limit). Unlike other resources to which we attach such value (precious metals, hydrocarbons), there really is no alternative to freshwater, other than the still expensive, environmentally-damaging, and energy-intensive desalination of sea water — a moment-in-time judgment always and forever subject to technological advances.

Thus, while we can say that humans will never run out of water (70 percent of the plane’t surface is covered by oceans and sea), we can say that good management/generation of fresh water resources becomes ever more crucial in a world characterized by a changing climate.

Two ways to characterize that change:

Climate change tends to de-humidify the surface and humidify the atmosphere — thus we speak more of vast water-rich atmospheric “rivers” while noting that surface rivers are losing flow all over the world.

Climate change is shifting atmospheric water from lower latitudes to higher latitudes, resulting in the:

Drying out of what I call Middle Earth (30 degrees north and south of the equator — home to well over half the world’s population, the majority of which still rely on the land/agriculture for income);

The “dis-tempering” (if you will) of what used to be the temperate band in which most of the Global North has thrived historically — i.e., those areas are increasingly subject to wild swings in precipitation and temperatures (the climate whiplash effect LA just suffered); and

The warming of the Arctic and Antarctic poles/regions.

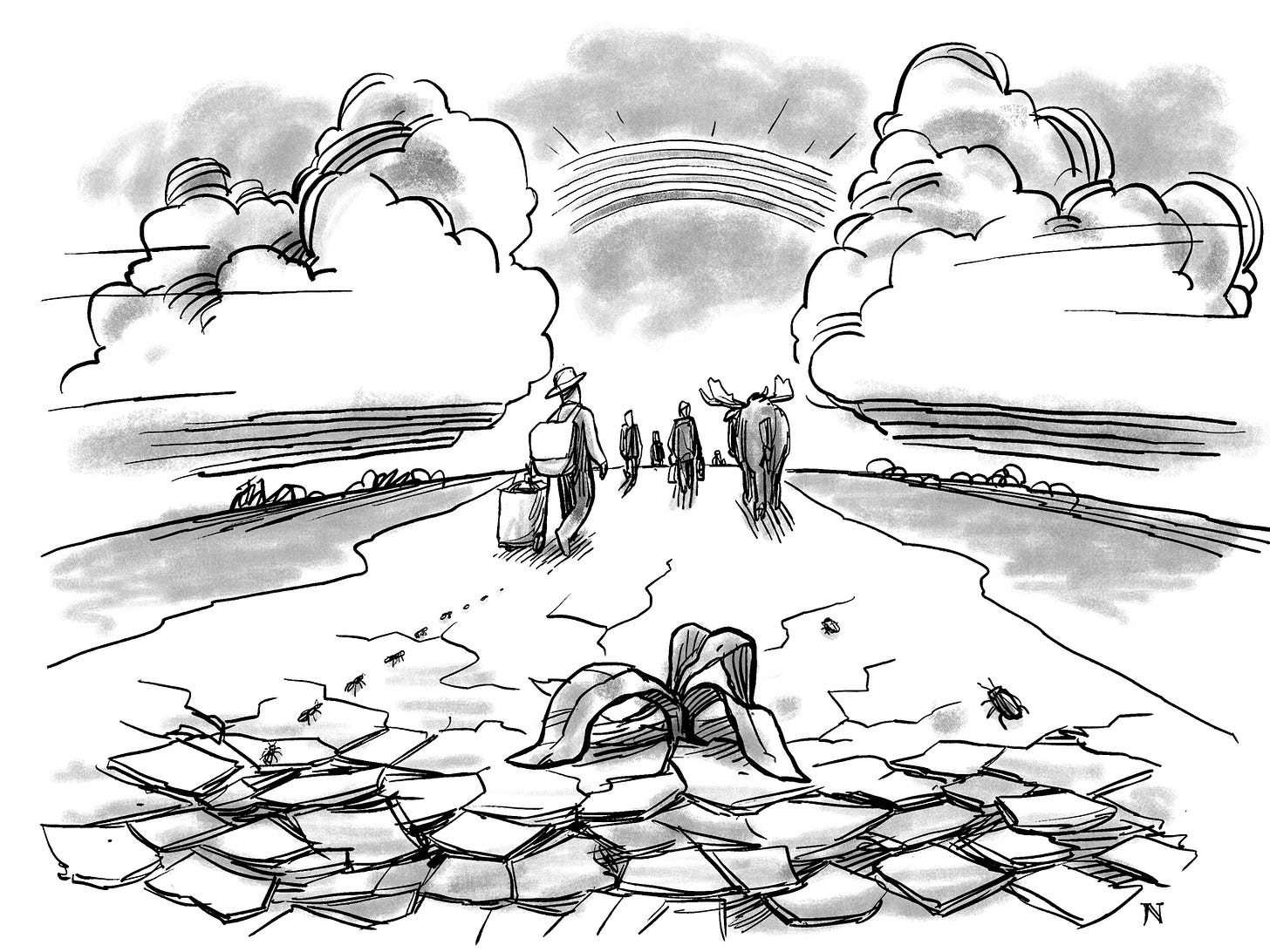

All of this shifting of water-cycles around the world is a big deal — a genuine transfer of what humans consider to be the most elemental wealth (“good” or arable land upon which agriculture can be conducted). Thus, as I like to note in the brief, Middle Earth is basically losing two Australias’ worth of arable land (approximately 15m square km, or ten percent of the non-Antarctic global landmass) while the Global North is gaining roughly the same — a completely unfair and uncompensated outcome of climate change overwhelmingly put in motion by that Global North across its long period of wealth creation — i.e., planetary injury; to include a lengthy stretch of colonialization of the Global South — i.e., insult upon humanity.

This huge disparity in water futures (Global North v Global South) is, in my estimation, the primary driver of the inescapable requirement of North-to-South integration schemes this century (political, economic, environmental, security, informational … migrational … the whole shebang). Upwards of two-thirds (5B) or more of the world’s population will face increasing water stress as Middle Earth’s “calendar” is increasingly and persistently booked up with days that equate to Saharan Desert-level rates of temperature and precipitation (like Phoenix last year suffering 100-plus days — in a row (!) — of 100-plus-Fahrenheit temperatures).

You can live in such an extremi-fied environment; it’s just going to cost a lot more to do so than if you followed the shifting of the temperate band toward the poles — a reality that makes us all non-arctic landlubbers increasingly view Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Nordic countries, and Russia in a new, more overtly covetous manner (see Trump saying the quiet part out loud recently).

This is why species the world over are systematically heading toward the poles and/or up in elevation: they’re simply tracking the corresponding “velocity” of climates’ movements across our planet, and that outcome represents the easiest of the three choices foisted upon all of us by climate change — namely

You move

You adapt in-place, or

You die (our planet’s ongoing Sixth Great Mass Extinction Era).

So, yeah, rich countries can adapt in place, like, say, the Netherlands has done for centuries (with regard to rising sea levels versus making agriculture happen in lowlands that would otherwise be too wet). A LOT of the Global North’s lowlands will be dramatically adjusting themselves to this spreading reality, with the US East Coast and Florida in particular as sort of the canary-in-the-coalmine to watch within the United States.

As for places and regions similarly stressed across the Global South … there we’re going to see either a:

De-populating effect (triggering far greater South-to-North climate migration), or

Some serious investment flow from North to South as part of latitudinally-centric integration schemes that arise in response and propagate themselves (i.e., Northern partners work to make Global South counterparts more resilient over time), or — most likely

Some combination of those two dynamics.

But, back to the relative disparity in water wealth East-versus-West:

Here’s a global map that displays where water flows from to where it flows to in what is called the “virtual water trade,” courtesy of the Water Footprint Calculator website:

If you add up all trade, calculating the water-intensiveness of every relevant product moved, then some regions are essentially water exporters and others are clear importers. Notice that the importers mostly lie across the lower latitudes of my Middle Earth and that the biggest exporters tend to be found in the higher latitudes (both North and South) — all of this being subject to great change in coming years.

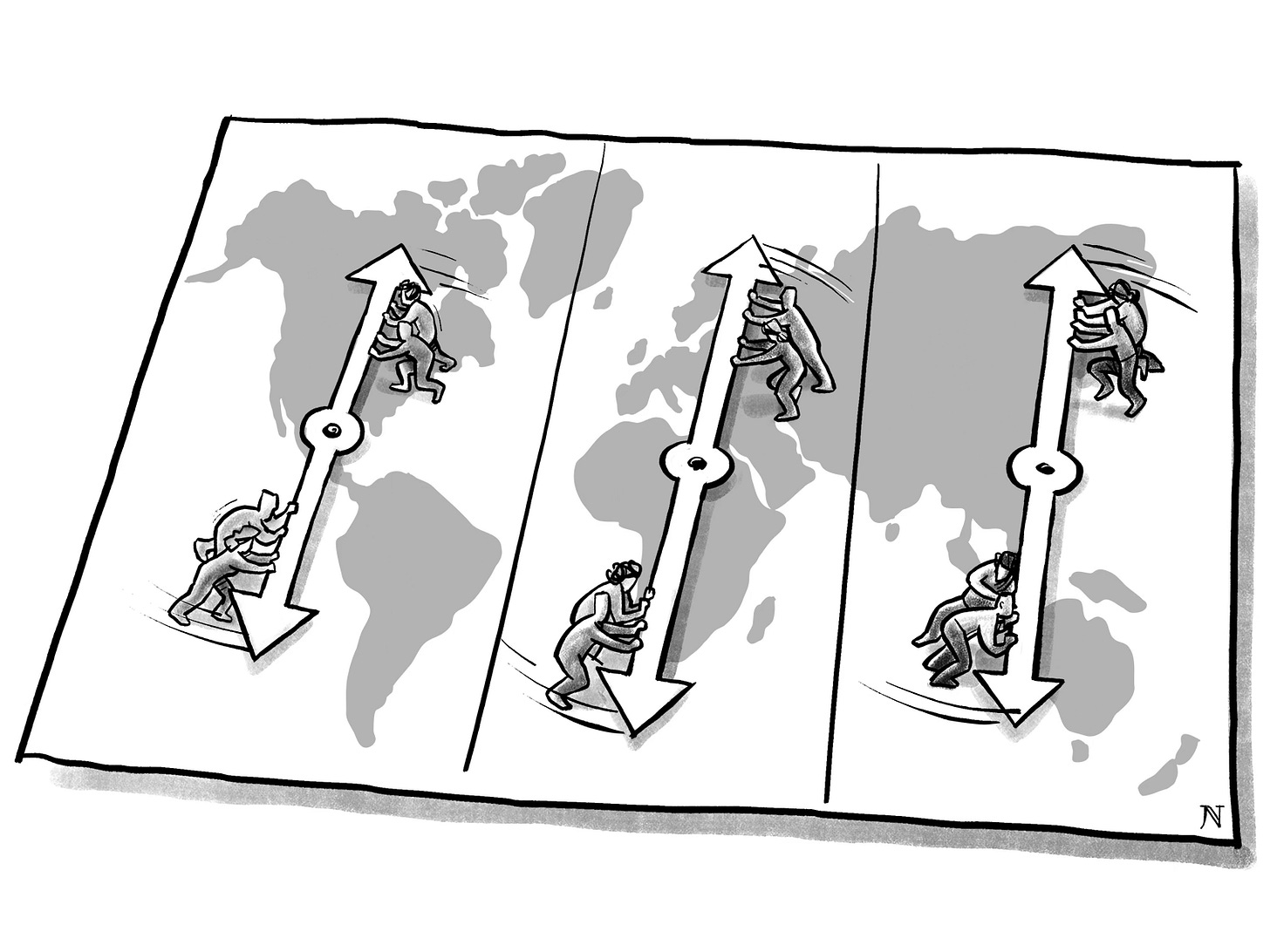

Per my current penchant to view the world in three vertical slices (West, Center, East), what do we see?

We see the following:

A Western slice overwhelmingly in the export “green” (noting our hemisphere’s water-poorer/importing Middle Earth-slice that is Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean)

An Eastern slice that seems okay enough for now but, given rising water requirements associated with various “risers” (China, SE Asian tigers, India) and the rising climate-change-driven drought threat among these same states, is decidedly heading toward a far more water-stressed, import-dependent future; and

A Center slice that — outside of Russia — is already importing water and will need to do so far more in the future.

Understand, this virtual water trade is mostly about food. Water goes into all sorts of products (cotton, for example), but the bulk of this trade is captured by the flow of food around the planet (water + sun turned into something more valuable and more easily transported).

If we go back up to my grain-flow map above, then, we can calculate that, of that moveable feast of grain transfers across the planet, when it comes to who actually has leftover grain to export, the Western Hemisphere and particularly North America is basically the OPEC of grains and thus the OPEC of the virtual water trade, and, by that, I mean, roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of the total net global reserve capacity (as in, we got more than we need and thus can trade it).

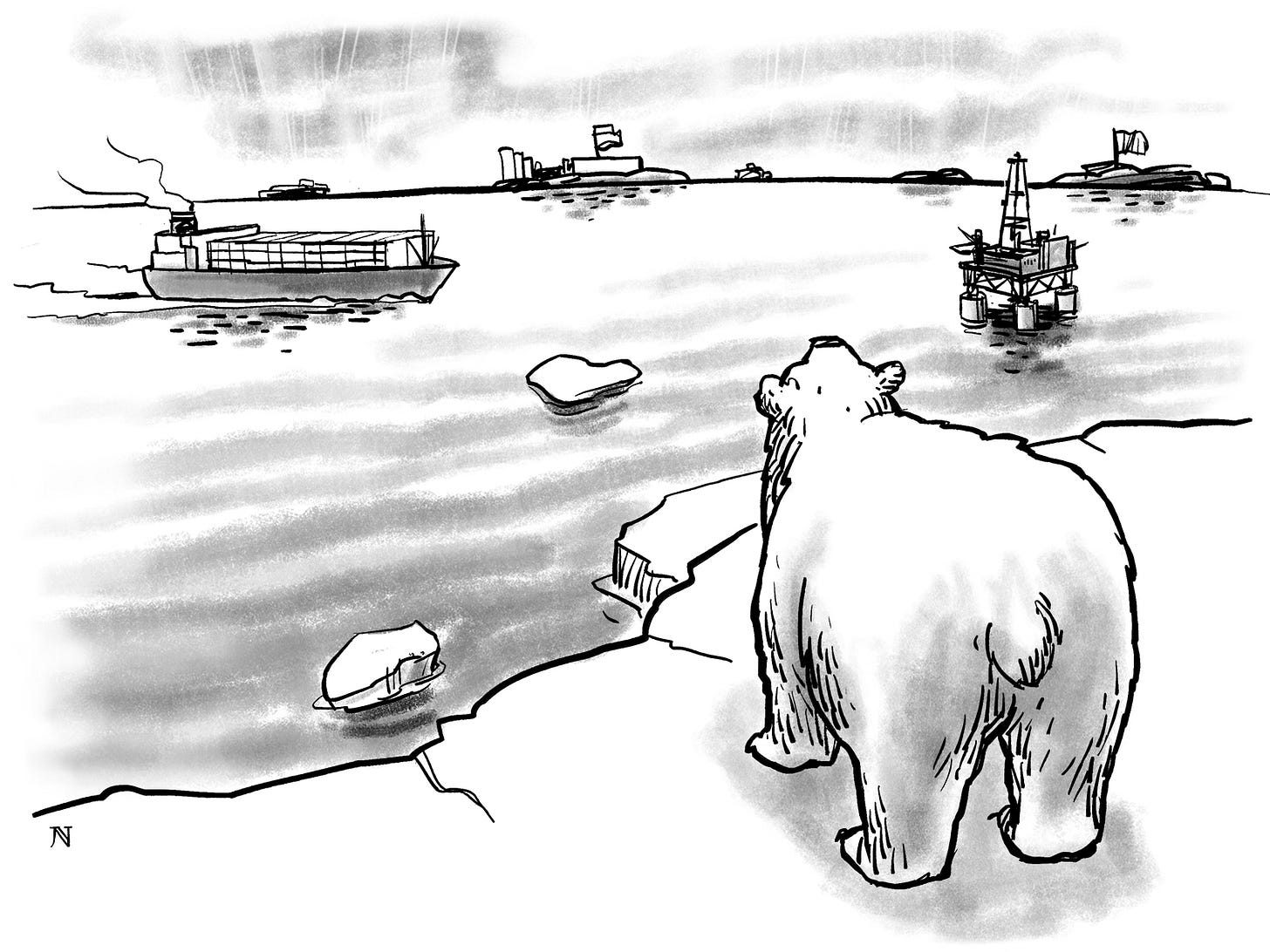

In a climate-changed world, I would argue that our hemisphere’s status as the OPEC of water becomes far more important than the actual OPEC’s standing in hydrocarbons, especially as the warming Arctic allows for “easier” — than in the past but still difficult — access to roughly 30 percent of the world’s remaining hydrocarbon reserves.

Again, looking at that virtual water-trade map above, this is why further integration among North America’s major players (Canada, US, Mexico, and — yes — Greenland) is logically slated to occur, however long the timeframe (and certainly it extends beyond Trump 2.0). The economic and strategic and security logic all just combine to make a powerful case that an integrated and united North America is the perfect 21-century superpower (as I described the proposed US-Canada merger in America’s New Map).

Ultimately, this logic of the Americas as the OPEC of water, propels these countries to work in concert through deeper integration with one another’s networks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.