I am a visual thinker, coming from a family where the males were typically (3 of 5) diagnosed as clearly dyslexic (a very new diagnosis back in my childhood). Mine was a marginal case (sub-clinical). I have trouble writing down numbers in sequence and I often drop words when I write. When I read, the words on the page are in motion — dynamic, but I can order them visually in my fashion. For me, nothing major, just a tendency. But, if you want to explain something to me, I need a picture of some sort, because that’s how I remember. When I do remember quotes, I don’t remember the words but their position on the page. When I read history, I HAVE to go look up all the people being discussed so I can see their image and know them on that level, otherwise I can’t keep anything straight in my head. To me, remembering a movie is to remember a series of camera movements — not the plot.

Good example: I can tell where I was seated for virtually every play and every sports game I ever attended, as my memories are highly tied to my perspective/point of view. This is why, when I buy NFL tickets, I always go with the home side so that, when viewing the game later on TV, it’s not reversed, which drives me nuts because it contradicts my visual memory and strikes me almost like an hallucination.

None of these tendencies makes me all that unusual or weird. Scientists estimate that we take in about 90 percent of reality — and information — visually. It’s just how we’re built and it makes sense evolutionary-wise, because good eyesight, pattern recognition, spotting and remembering faces … these are all hugely beneficial to survival … as in, I recognize that face!

So I’ll remember your face, then your voice, and not much else about you.

In school, verbal instructions often baffled me, but a visual example was everything. [So yeah, I REALLY liked comic books.] Absent one, I’d have to create my own, show the teacher to make sure I was doing it right, and then proceed (a very annoying process for some teachers). Otherwise, I’d be tempted to look at other people’s “work” — a big no-no with the nuns but a good tell on a visual learner.

Combine my visual-learning bias with a focus on the future and voila! You have someone naturally drawn to science fiction TV and movies. And yes, I HAVE to see the movie before I can enjoy the book — or even follow it. I have tried it the other way and it never works for me.

As I have indicated here many times, I grew up on Star Trek reruns as a kid — always at 4pm after school. That conditioning of my brain taught me to presume that there are always answers, solutions, ways ahead — often tied to technological advances (which Star Trek previewed galore) — whenever problems are encountered (Kirk’s most telling phrase being, “I don’t believe in the no-win scenario”).

This is why I so strongly prefer scenario-based planning when it comes to anticipating future events, trends, worlds, etc. Show me a briefing on the future that lists trends in bullets and my eyes will glaze over, but give me a visual cue (often referencing a sci-fi movie) and I’m instantly there, looking around.

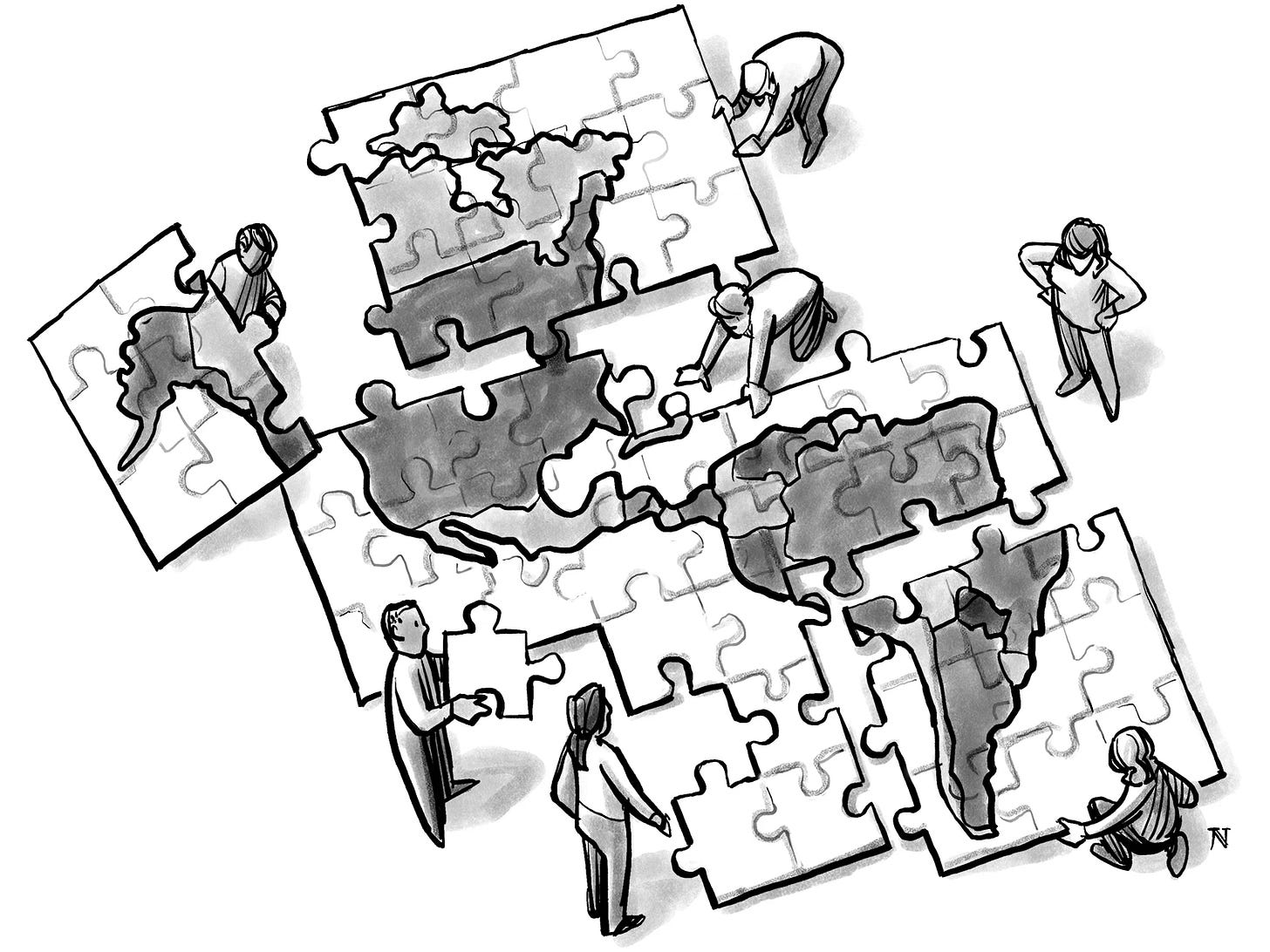

In this way, working the future beat is all about matching visualizations to story-telling. The combination is how you establish — quickly — a sense of the ordering principle and rules of this future environment. You need to build the world first, and then let the story-telling fill itself in.

I first learned of the power of such visualizations when I ran a multi-year research project at the US Naval War College looking ahead to the possibilities surrounding the Year 2000 Problem. Back in 1998, when I began the work, there were all sorts of crazy predictions and scenarios being tossed about that either freaked people out unnecessarily or caused them to completely tune out because … what the hell were you supposed to do?

In this work, assigned to me by the incoming president of the college, the three-star or vice admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski, I was supposed to imagine, through the Delphi method of assembling and querying experts from diverse fields, how this could all unfold along both good and bad lines.

The goal of the work was to eliminate shock while accommodating surprises — a key distinction in this, my personal formulation. Surprises unfold within a known world and a reasonably understood pathway. Shit happens, as they say, but we’re able to contextualize it. So, surprising yes but shocking no.

Shocking is the feeling of I had no idea it could be like this! That is truly being overtaken and overwhelmed by events — serious surrender.

And that’s exactly what you target for elimination when you’re building competing scenarios: you want to be able to locate the dynamic in question within a field of comprehension, or a cone of plausibility, as some call it.

[SIDENOTE: remember that political science begins with the question, Are humanity’s paths to happiness many or one? Many = democracy and one = autocracy.]

Just this image alone is everything to my understanding: the past funnels you into the present and the combination frame the limits of plausibility. There is a baseline trajectory of things staying pretty much the way they have been and are, but there’s also a range of possibilities (alternative futures) as that trajectory expands into the future.

You could talk that mess to me all day and I wouldn’t get it. But show me this image and I get it immediately.

Eliminating shock, then, is all about getting your plausibility limits correct — i.e., how wide your aperture when viewing the future. To achieve that, you rely on what I call the “inevitabilities,” or the structural changes you can predict with very high likelihood (like climate, demographics, basic human economic behavior, characteristics of modernization regardless of culture, etc.).

That’s your deterministic streak, which, for me, is all about the economics arising from the technology (very Marxist in origin). The economics race ahead of the politics, generating regular crises and resolutions (revolutions). Same thing with technology racing ahead of security. When those gaps get too big, ruleset gaps emerge (people lack rules for certain dynamics as they emerge) and when enough of these gaps emerge, crisis ensues, triggering structural changes defined first and foremost by new rules (the new normal achieved). [For Marx, that new normal was communism, because he had such a dim view of humanity and society being able to adjust and adapt — his great failure of imagination.]

This is basically what I’m describing with my current brief’s BLUF slide (or Bottom Line Up Front slide).

There is an implied Cone of Plausibility here, along with an implied OODA loop and even an X-Y of sorts.

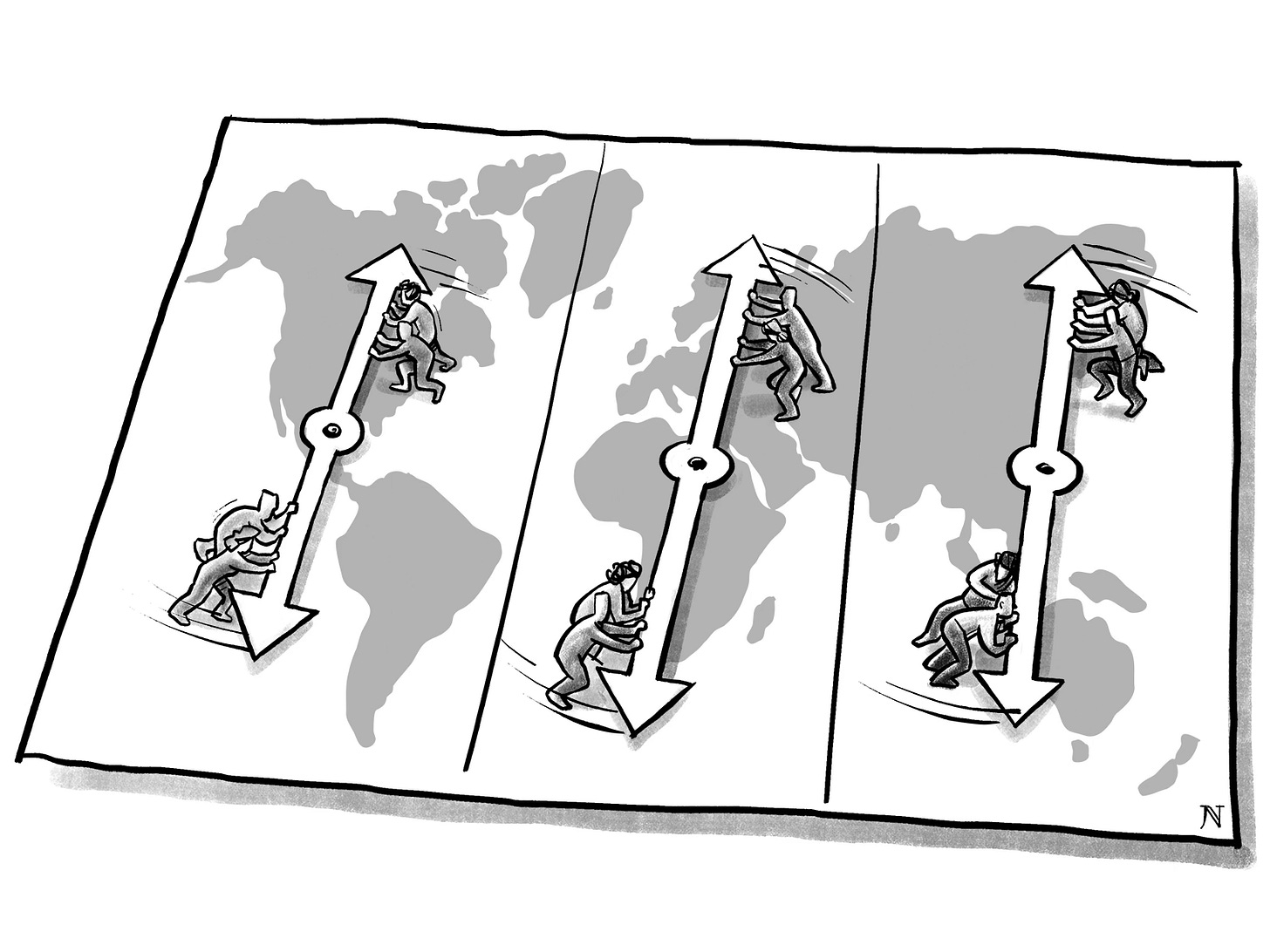

The past is US-style globalization, which I narrow down in the present to three big outcomes, which then create the inevitability of North-South Integration — a range of plausible future trajectories.

As we go from past to future in this trajectory defined by certain inevitabilities over the next half century, there are competing paths from the X-Y’s lower-left worst-case to the upper-right best case, here defined as the regionalization imperative and the superpower brand competition — two system-wide dynamics that push and pull at the same time, yielding this cone I call the Zone of Turbulence and positing a New Normal (with all manner of new rules) on the far side of this experience.

Similarly, from left to right, I want you to observe the past, orient yourself to the present, and then, confronted with the Cone and its alternative futures, decide on the strategy you wish to undertake, allowing movement toward action.

So, whether it’s the Cone, or the OODA loop, or the X-Y, you’re really doing the same thing in each, with the key output being you help your audience visualize those developments/possibilities/pathways.

Again, surprises are guaranteed. What you seek to eliminate are shocks: you want your audience to have every idea that this could have happened.

Surprises are opportunities while shocks are true crises. I want to flip my crises into opportunities, and the best way to do that is to visualize the future comprehensively so as to eliminate that potential for shock (Yes, we had considered this outcome and this was our response.).

Chaos is just giving in to shock and behaving badly as a result. People constantly over-estimate this pathway because, if it occurred (actually) as much as it is declared, humanity would have disappeared long ago.

Complexity is the enemy: it creates ambiguity and volatility, which, if not properly framed and visualized, leads to unreal uncertainty, which leave you open to shock.

I love surprises; I don’t like shocks.

And so, I organize my thinking to accommodate the former and eliminate the latter.

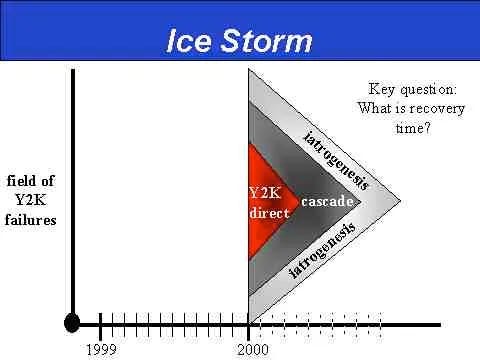

An example drawn from my Y2K work (one of the great educations of my life when it comes to parsing and thus understanding what we now dub our VUCA world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity):

How to imagine the onset of the Y2K problem?

How big?

How pervasive?

How bad?

How destructive?

How complex and interrelated?

When I first imagined describing the Cone of Plausibility here, I was baffled.

But then I ran a workshop with experts and the right visual analogies surfaced: weather disasters.

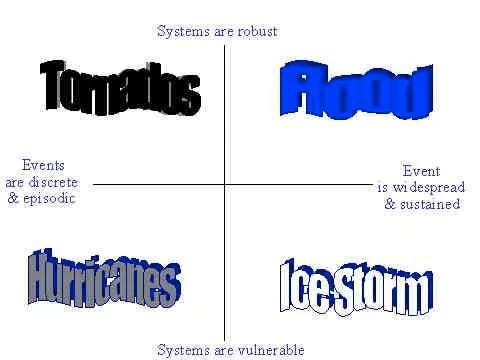

So, we started with the X-Y and came up with the four weather analogies:

Those were the names arrayed to suggest the Cone, but it was the visuals for each that sealed the deal.

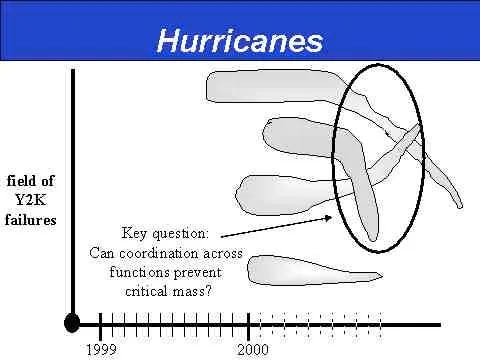

Discrete and episodic unfolding of failures revealing system vulnerabilities = pathways of hurricanes.

Similarly discrete failures but systems are more robust, so the damage is often isolated and seemingly random = tornados.

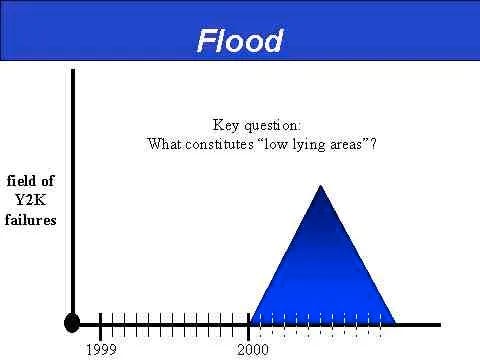

Widespread failures but impacts concentrated across the weakest systems (low-lying areas) = flood.

And then the most comprehensive failures yielding a shutdown of most dynamics = an ice storm that reveals all manner of system vulnerabilities (once A fails, B follows, triggering C, D, and E).

Everybody I briefed instantly got these analogies because they were simple, and accessible, and we provided visual imagery that matched their personal memories.

And, once I had them inside that bounded Cone, we could go anywhere to uncover all manner of surprises while keeping our reception sufficiently contextualized as to rule out shock: Yes, we had considered that possibility.

By admitting it could be both very handle-able and very un-handle-able, people were able to enter these alternative futures with some level of understanding and thus confidence — the basic requirements for strategic planning.

Why re-argue/re-present all this stuff?

We’re at a weird point in our political and security responses to both our economics (globalization) and technology (AI) racing ahead of known rule-sets, triggering a great deal of that VUCA-perceived fear.

If you want to puncture that giant cataract in your vision field (VUCA), you need to frame dynamics so as to reveal the inevitabilities and, by doing so within that Cone of Plausibility, explore the possible pathways forward, in turn revealing choices that today might seem inconceivable but won’t be as we move forward in time.

Visualizing all this is crucial to unlocking your brain and allowing it to operate on this highly conceptual level.

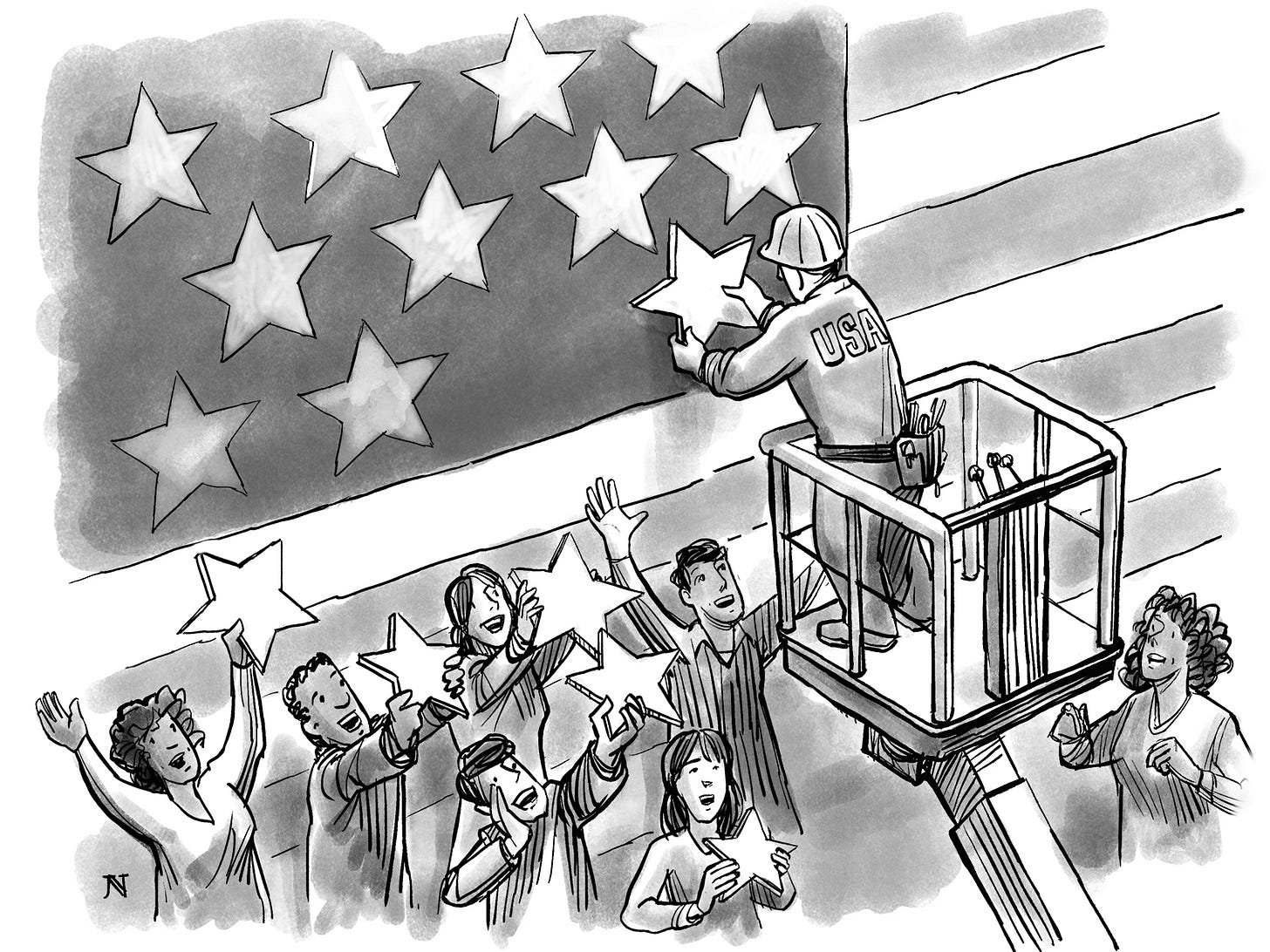

So, no, there are no silly pictures. They all tell us something about choices yielding outcomes, or crises segueing into opportunities.

These are the underlying reasons why I work now for Throughline — a firm that helps leaders visual futures, allowing them to move from intent to action.

See the visuals + follow the logic = move from VUCA to understanding and action.