Couple of interesting analyses that go well together.

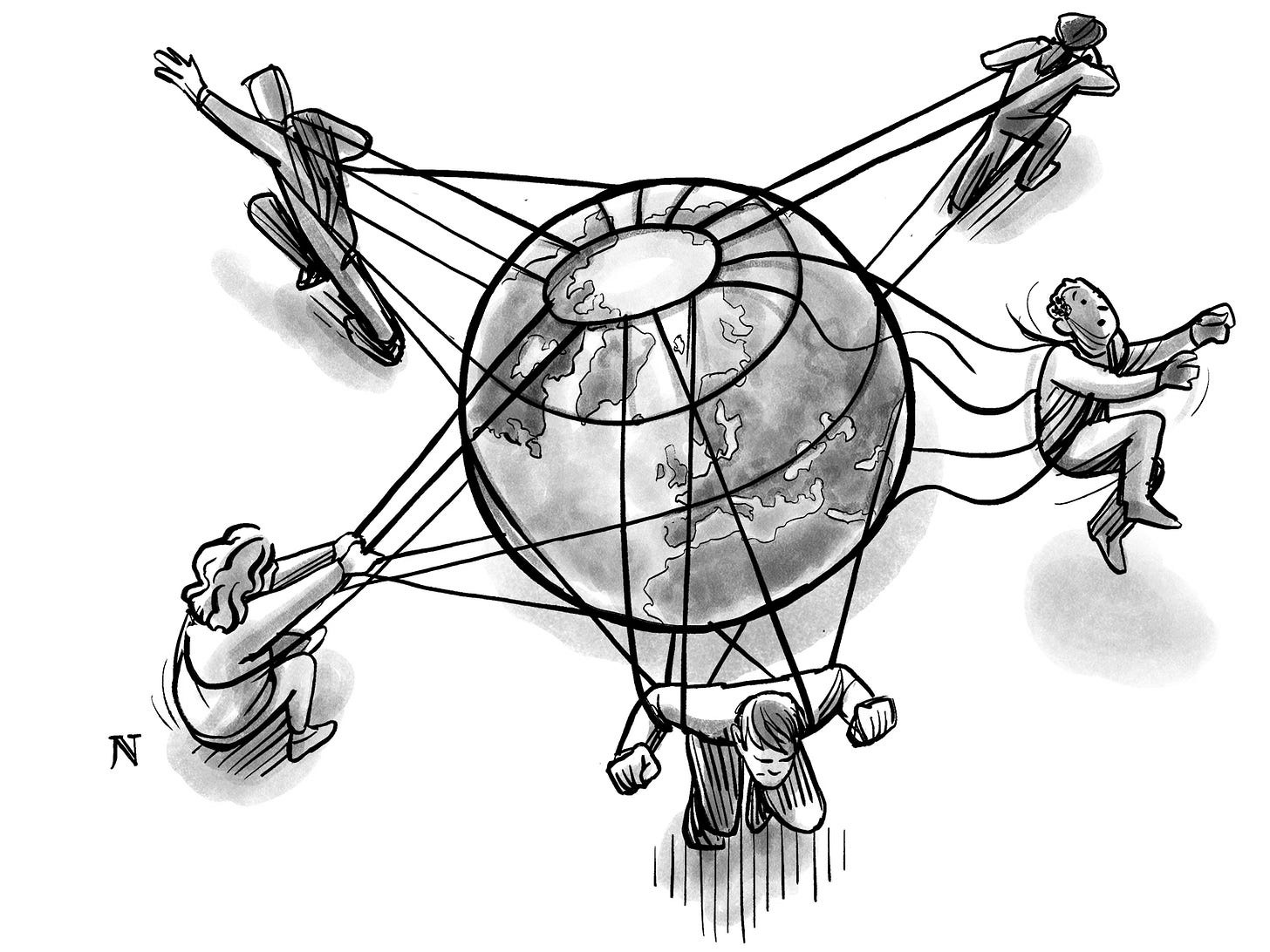

The first is a magnificent defense of the positive outcomes associated with hyper or peak globalization (widely dated as 1990-2008 or 1990-2020, depending on the perspective). It was during this goods-drive trade expansion, aided by a radical decrease in transport costs, that a lot of good things happened.

The Foreign Affairs article (A Requiem for Hyperglobalization: Why the World Will Miss History’s Greatest Economic Miracle) makes a great argument for the macro benefits of trade connectivity — not policies per se but just the sheer connectivity.

The prime evidence of these benefits is what has been called the Great Convergence of economic growth rates among developed (which grew) and underdeveloped (which grew faster and thus narrowed the gap with rich countries) economies. This was a huge reversal of global fortune, which, going back through five centuries of European colonial empires, had unfolded overwhelmingly to the benefit of the advanced West relative to the East and Global South.

The radical expansion of global trade connectivity that characterized hyper globalization changed all that by lifting those “boats” that had long suffered under colonial rule and its long aftermath — in short, a more equal world emerged.

From the article:

Some poorer economies had already experienced success in the twentieth century—South Korea and Taiwan prospered beginning in the 1960s, followed by Indonesia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Thailand. But the era of convergence that began around 1990 stands out for its ubiquity of remarkable growth, extending to a plurality of developing countries. As a group, they started reversing their previously bleak economic fortunes. The world saw a historic decline in poverty not just in China and India but also in Latin America and, starting in the mid-1990s, in sub-Saharan Africa.

Every country pursued unique policy choices. But although ideology and favorable macroeconomic conditions helped power this astonishing era of convergence, arguably the most important factor was hyperglobalization, the rapid increase in trading opportunities beginning in the late 1980s. It is uncanny how convergence coincided in timing with hyperglobalization: they began together in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when developing countries became more exposed to trade and then started growing faster than their rich counterparts. Hyperglobalization and convergence also peaked together. And since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, both phenomena appear to be coming to an end.

That is arguably one of the best things ever to happen to our world throughout the course of human history, healing a vast wrong. But it came with a price: the far more competitive global economic landscape in which we now find ourselves, along with the more contested geo-political landscape — thanks to all those “risers” but China in particular.

As I have long noted: we sought all this, going back to the end of WWII. We wanted to be done with great-power world wars and, thanks to the invention of nuclear weapons, the world finally got its military Leviathan that said this far and no farther. We sought convergence (who can be against it?) and we sought multipolarity.

But, when we got both — along with the greatest period of great-power peace in human history, they scared us in addition to demanding a more inventively competitive stance from us. As modern, US-style globalization’s “market maker,” or the great power most concerned with the “state of the game” and not just its own standing within that game, the US naturally reached an endpoint in that decades-long quest to fix a world so that great-power war was no more.

In short, we needed to shift away from our strong market-making roles (leader of this and that) to one more overtly “market playing” — i.e., looking our for ourselves, making America great again, etc.

That shift coincided with the Great Financial Crash of 2008 and Obama’s election. He promised nation-building at home and a more restrained global leadership role. Trump later amped up that instinct considerably, and Biden, while softening Trump’s often wrongheaded tactics, has largely kept that attitude in place. No matter who wins in the fall, we’re looking at further retreat from global leadership: Biden’s being slow and steady and Trump’s being abrupt and chaotic and destabilizing.

Worse, though, is the reality that the North’s growing trade protectionism is finding acceptance across the Global South as both sides swallow the notion that hyperglobalization was somehow bad:

By joining the West in repudiating globalization, however, developing countries—especially larger emerging economies—have become complicit in biting the hand that fed them. And some Western progressives have swapped their cosmopolitanism for nationalism without much discomfort or remorse, justifying this shift on the doubtful grounds that globalization harmed developing countries. These days, the demise of hyperglobalization is often met with relief, even celebration.

But the world, and especially developing countries, may well look back on it and the era of convergence it underwrote more elegiacally, the sense of loss compounded by the guilt that perhaps not enough was done to defend it. Hyperglobalization’s death ought to elicit mixed feelings—if not lamentation, then at least not cheerleading. It is open to debate whether protectionist measures by industrialized economies will help to combat climate change or reduce dependence on or conflict with China. But for developing countries, hyperglobalization undoubtedly played a critical role in their post–Cold War economic renaissance. The alternative to hyperglobalization—developing economies become locked into regional and geopolitical trading blocs and struggle to exit from commodity dependence and tap into the more dynamic manufacturing and services sectors—may well prove worse.

But this is where I see — and seek — an “out” or way ahead in my book America’s New Map: hyperglobalization was fundamentally an East-West connectivity scheme, which, by extension, triggered an East-South connectivity push that continues to this day in things like China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The West wanted the East’s cheap goods (made possible by Asia’s sequential demographic dividends: Japan—>Tigers—>China—>SE Asia and soon India) and, to make that happen, the East needed to radically expand trade connectivity with raw material producers throughout the Global South (to a degree replaying colonial-era trade balance/flow inequities).

But now, with the West feeling threatened, it wants to “decouple” from the East (the “China plus one” diversification scheme you hear about from so many Western multinational companies) just as that East (China, India, Russia, etc.) is turning South to both balance its loss of access to the West (due to rising trade protectionism there and overall geopolitical tensions) by “winning” the Global South by meeting that cohort’s expanding middle-class demands for a permanently improved standard of living.

In effect, then, hyperglobalization is at risk — in the largest sense because of the West’s growing nationalism, xenophobia, protectionism — right at the historical moment when the Global South is seeking a locked-in status when it comes to achieved prosperity. The West risks slamming the door on those aspirations RIGHT AS climate change hits those lower latitudes and sends those economies into a lengthy downward spiral, thus reversing the magnificent gains of hyperglobalization’s long stretch of success.

That’s just the economics.

If you layer in the politics, then we know already, from past historical experience, what happens when new middle class ranks are suddenly thrown back into poverty or even just severe uncertainty: namely, they turn to radical Left (socialism) and Right (fascism) solutions — both of which exist nowadays in plentiful amounts (Trumpism included).

Instead of stepping forward with progressive solutions favoring the preservation of the middle class (think of the Roosevelts Teddy and Franklin), America is devolving right when its political leadership could play a positive and decisive role both at home and abroad.

How?

We do so by pushing North-South integration as the best possible variant of the near-shoring protectionist impulse so intensely animating our politics right now (to include tackling popular fears of overwhelming Latino migrations to our shores by addressing those impulses at their sources down south). If we’re going to de-couple from China and playing a harder, more protectionist game with both the West and East, then we have to give somewhere else to avoid a complete retreat from global leadership.

We can’t just be running from everything; we need to be running toward something.

Which gets us to the second article of note: America Isn’t Leading the World.

Making China our enemy isn’t really leading, nor is reducing the perceived “international community” to just our advanced-economy buddies:

There is more to global leadership than backing friends and beating back foes. Leaders, in the full sense, don’t just remain on top; they solve problems and inspire confidence. Mr. Trump barely pretends to offer that kind of leadership on the world stage. But precisely because most U.S. officials do, it is all the more striking where American power stands today. Never in the decades since the Cold War has the United States looked less like a leader of the world and more like the head of a faction — reduced to defending its preferred side against increasingly aligned adversaries, as much of the world looks on and wonders why the Americans think they’re in charge.

Big ouch! Mostly because that judgment is so damn accurate.

Climate change is here as a global problem seeking global leadership.

Our broken immigration system is routinely described as our worst near-term national security issue (climate change being the long-term variant).

Both can be addressed by US leadership that shifts from our long-term fixation on West-v-East to a new appreciation of North-v-South.

Hyperglobalization got the world so far in solving the North-South gap, but now the North is collectively in danger of reversing that convergence dynamic as it freaks out over great power competitiveness and tensions — all East-West in orientation.

If America wants to lead right now, it needs to break that mold, turn North-South, and address, through a new vision of North-South trade and investment and — ultimately — political integration, our two big problem sets right now (immigration in the near/medium term, climate change in the medium/long term).

That is where our leadership needs to be steered, versus being lost to our manias over Middle East peace, the Russian threat, or the Taiwan scenario — all tailbones of the Cold War (i.e., useless until their suffer “injury”).

America is indeed at a major turning point in global history.

The sad thing is, we’re choosing now, in our national election, between two candidates who offer painfully little vision or leadership to a world desperately seeking both from us.

And no, that’s not a call to waste your vote on third-party types. That’s just a way to take a personal pass to no practical effect.

Frustrating times for anyone dedicated to thinking long term, is it not?