The return of the Scoop Jackson Democrats

Harris's "muscular progressivism" or "progressive patriotism"

Foreign Affairs is out one of its star-studded editions that plumbs the depths of conventional wisdom. The theme is “America Adrift,” which is forgivably accurate enough. Such lamenting is sort of an alliterative tradition for foreign policy types, but usually when their side is out of power and the other isn’t acting sufficiently “realist.” Walter Russel Mead brings up his Jeffersonian/Jacksonian/Hamiltonian breakdown, as usual, arguing that we’re necessarily in the Hamiltonian way today — if we’re paying attention:

The driving force behind the Hamiltonian renewal is the rising importance of the interdependence of corporate success and state power. In the heady days of post–Cold War unipolarity, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and many leading companies started thinking of themselves as global rather than American firms. Moreover, it seemed to many foreign policy thinkers and officials that the distinction between U.S. national interests and the needs and requirements of the global economic and political system had largely disappeared.

I like the argument in this sense: Having abandoned our market-making role around the time of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, we have since struggled to define a genuine and healthy balance between that enduring instinct to shape the world system and our natural desires to do well ourselves in a more competitive landscape (acting more like a regular market-player in this multipolar world of our creating).

The Hamiltonian ethos does seek to balance the two instincts — at least abroad: we play hard but with an eye to shaping the whole when and where we can. Clearly, for now, we need to focus on competing with China and it’s clear ambitions to shape the world system amidst the continuing rise of a majority global middle class increasingly based in the Global South — a place America generally ignores as it focuses on its traditional targets of Europe (v. Russia), East Asia (v. China now), and the Middle East (v. Iran since 1979).

That’s your history of US regional foci across the Cold War: first save Europe (1940s-1950s), then contain communism in Asia (1950s-1960s), then shift to the Middle East under Nixon/Ford/Carter (1970s) before reverting to Reagan’s “high ground” snatching (Star Wars) vis-a-vis the Evil Empire (1980s). Point being, we’re still focused on all three, with our brain-dead strategic tendency being to assume we must be able to militarily stop each region’s baddie in their tracks even under conditions of simultaneity:

What if Russia attacks NATO and …

China goes for Taiwan and …

Iran goes directly at Israel …

Do we have a military that can dominate all three battle spaces at the same time?

Because, if we don’t, we’re totally screwed and so is the world!

A bit melodramatic and self-centered, ja? But hey, that’s who we are. We either save the world or it’s all going to hell! There is no in-between and there is no trusting the world order we established and sustained for so long.

Our dominant interpretation right now is that the US rules-based order is under assault, which is our way of saying that other superpowers are now more openly seeking their interests in aggressive ways — something that, in the good old days, was left ONLY to the United States whenever it saw fit (our long history of system-shaping/preserving wars and crisis interventions).

Sigh!

When we engaged that sort of behavior, it was a positive thing. Then, when we started walking away from that muscular market-making role and others naturally stepped into that vacuum, that was automatically a very bad thing — now recast in Cold War outlines as democracies-v-autocracies.

Fair enough on the name calling, but must we re-adopt the whole three major regional contingencies mindset of the past?

Because, honestly, we’re not up for that anymore. We won’t sacrifice all that butter at home for all those guns abroad.

We do need a balance, and while a Hamiltonian one of enlisting the private sector makes a lot of sense in my vision of the US-v-China competing to satisfy the demands and desires of that global majority middle class (where the struggle between autocracy [from Right or Left] versus democracy [middle ruling itself] is centered this century), there’s still too much of a populist impulse at home for that to work openly.

What I mean by that: we’re in a progressive era in terms of need (we need to regrade our domestic economic landscape to rebalance rich-v-middle-v-poor), and we’re getting closer with party responses (reasonable on the Left but still too regressively backward-looking on the overly populist and xenophobic Right). Per Benjamin Friedman’s notion (Moral Consequences of Economic Growth), America can only be the benign, market-shaping progressive force abroad when its middle class back home is happy. Thus, an openly corporatist approach to foreign policy (very Hamiltonian) just won’t fly today. And it certainly won’t attract the sustained support of upcoming generations.

We currently feel that corporatist instinct vis-a-vis China, and it’s not wrong. But the more broadly-framed truth is this: we need to trust-bust a lot of these IT giants at home, but, if we do so, we risk knee-capping our nation in the grand race with China to wire up that Global South, capture that global middle class’s hearts and minds (after adequately addressing their stomachs and wallets), progressively rule the resulting infosphere, sucking up all that Big Data and, on that basis, prevailing in the AI race!

Whew! It’s a lot, right?

But, to me, that’s the real race here. Not Ukraine, not Taiwan, not the Middle East, where, in each instance, we’re dealing with very OLD fights stretching back decades. The future is winning the Global South amidst globalization’s wave of North-South integration forced by climate change and demographics and that emergent global middle class, and to shape that market and win that competition (that China is leading by a ways right now), we need those IT giants to remain … kind of … giant, frankly. Otherwise we won’t keep pace with China’s national IT flagship companies.

So … the Hamiltonian approach is not workable in an era that demands progressivism at home (the true nation-building we’ve been struggling to define since 2008). It’s just too mercenary and thus vulnerable to attack from the populist Right (Mead’s Jacksonian vein).

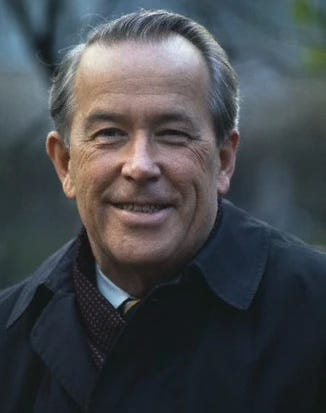

America thus needs a sort of split personality right now: muscularly engaged abroad but deeply progressive at home. To me, then, the right Jackson here is Henry or “Scoop” Jackson, the fabled “senator from Boeing” (1953-1983) who nonetheless was a clear progressive on domestic issues.

I have long described myself as a Scoop Jackson Democrat: activist at both home (progressive re-grader of the economy) and abroad (muscular interventionist). Usually, when I say that, nobody remembers my preferred Jackson, but he remains the model: biased toward the little guy at home but openly corporatist in the global competition (the what’s-good-for-GM-is-good-for-America kind of vibe).

Scoop was the epitome of the “Cold War liberal,” and that split-difference comes closest to what we need today: market-re-making at home, purposeful market playing abroad.

That’s a tough balance, indicated by my lament that, while I vote Democratic, I’ve worked far more for Republicans across my career (really, no contest).

Frankly, there’s not a lot of people or politicians standing up for that middle ground today … except maybe we’re getting a decent approximation with Harris and Walz and what some (okay, just one NYT story) are calling their “muscular progressivism” or “progressive patriotism.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.