The Youth Bulge of All Youth Bulges

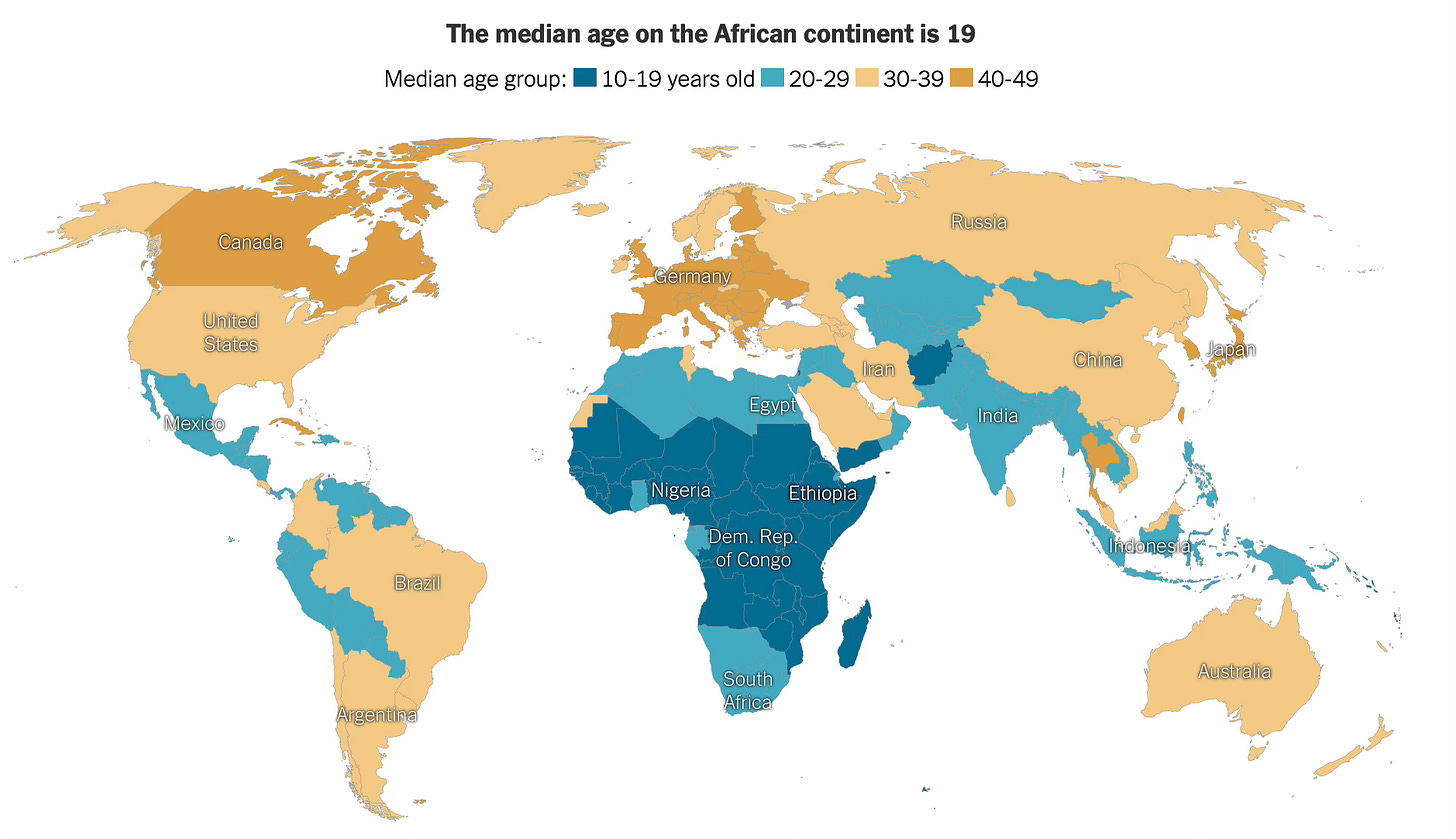

Come mid-century, we will all be living in Africa's youth culture

Really solid NYT article exploring a subject very familiar to me: the inevitable demographic rise/transition of Africa this mid-century.

Some key bits:

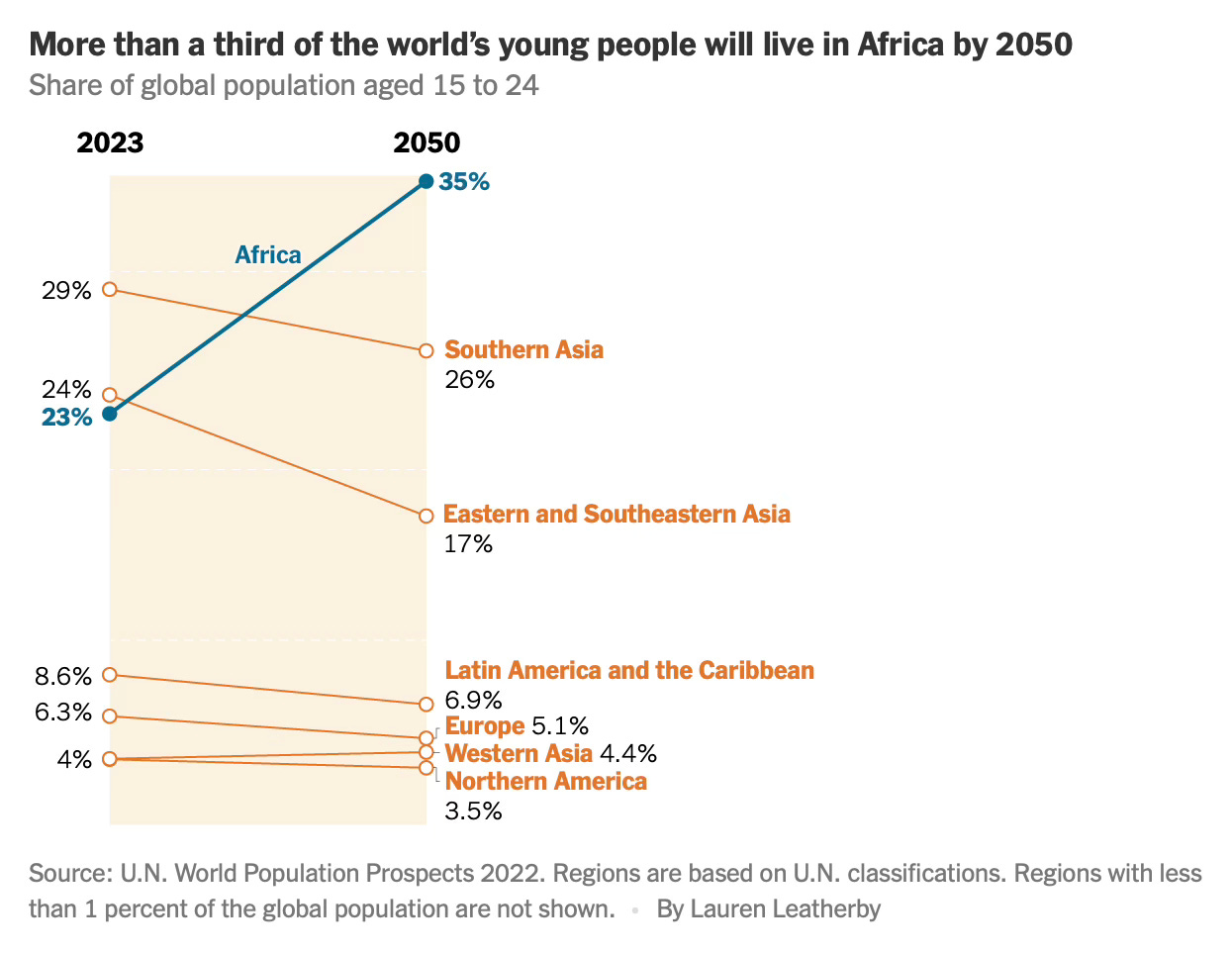

By 2050, one in four people on the planet will be African, a seismic change that’s already starting to register.

You can see it, the article argues, in music and culture already, which is only natural, as youth tend to drive such developments in any society, and so, as Africa begins to dominate global youth ranks, it will dominate global youth culture and — by extension — global culture in general.

For now, it all seems wonderful from an emerging markets perspective:

Businesses are chasing Africa’s tens of millions of new consumers emerging every year, representing untapped markets for cosmetics, organic foods, even champagne. Hilton plans to open 65 new hotels on the continent within five years. Its population of millionaires, the fastest growing on earth, is expected to double to 768,000 by 2027, the bank Credit Suisse estimates.

But then the piece hints at the economic caveat to all this:

You can see it in the waves of youth who risk all to migrate, and in the dilemmas of those who remain.

What we are witnessing here is the world’s last great demographic transition, which goes sequentially from baby boom to youth bulge to demographic dividend (lots of workers relative to dependents) to the dreaded silver tsunami!

We in the North have all pretty much passed through the dividend and await the tsunami — China being the latest superpower to ride that cresting.

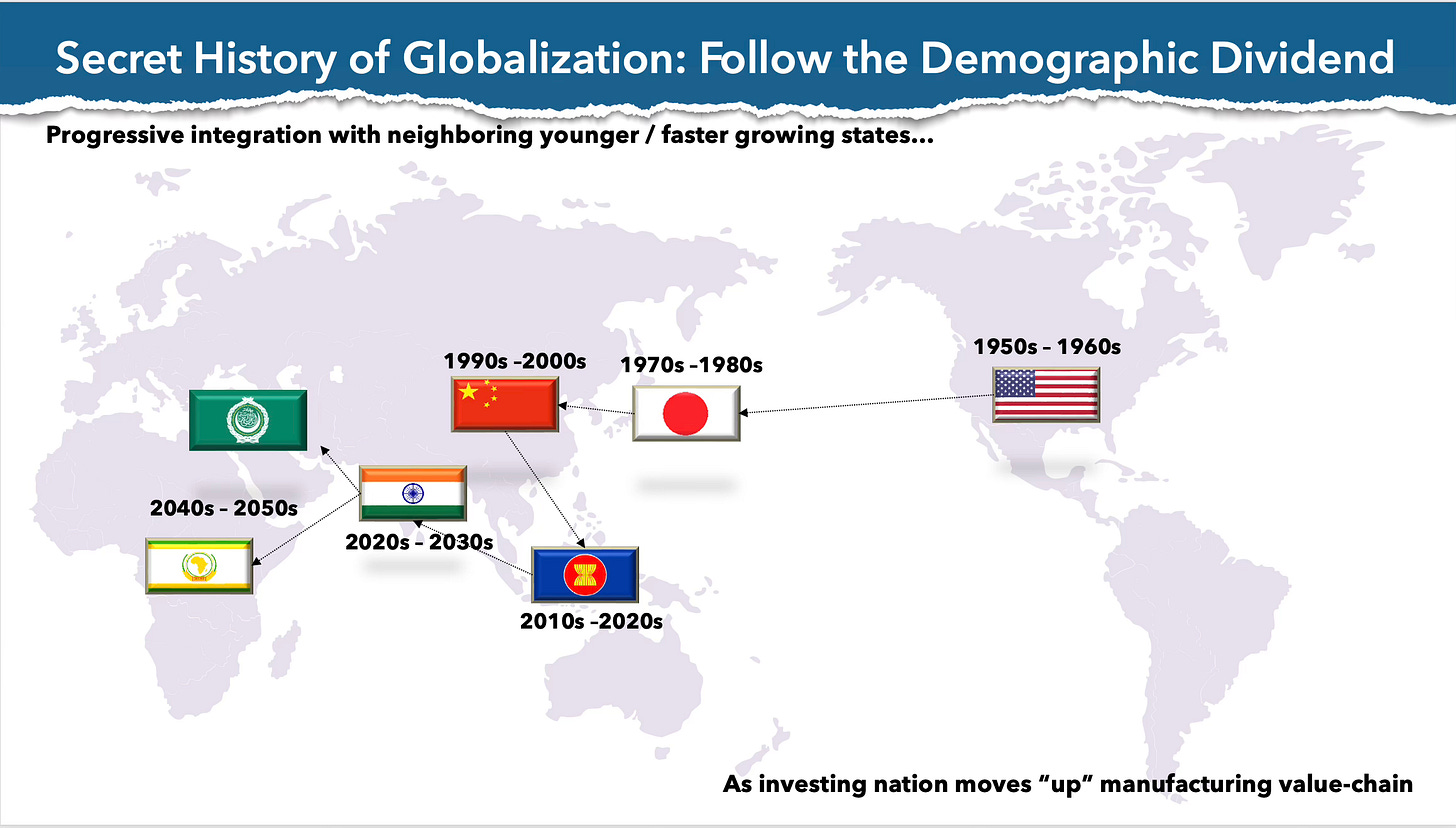

This what I describe in America’s New Map as my “Secret history of globalization: Follow the demographic dividend” (Thread 14):

America escaped World War II demographically and industrially unharmed, only to immediately enjoy a baby boom that allowed it to capitalize on its supremely advantageous position as sole surviving economic superpower. America was indeed great but sought to share that greatness with others, engineering the economic resurrection of former enemies (Japan, Italy, Germany) and encouraging Western Europe’s cloning of its integrating political union (the EU).

Taking advantage of America’s largesse, Japan’s three-decades-long post- war demographic boom fueled its amazing industrial rise while preordaining its rapid aging. Tokyo and its imitators, known as the Four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), were too successful for China to ignore, particularly as the Soviet Union’s rapid dissolution confirmed the eco- nomic backwardness of state socialism.

China’s own demographic dividend (1980–2010) followed closely on Japan’s heels, only to peak during the Great Recession. Not only have factory wages risen ever since but now Beijing also faces a loss of 200 million workers by 2050.

Fortunately for China, globalization’s next great pool of cheap labor emerged next door in Southeast Asia, to which Beijing is already directing its lower-end manufacturing assets and investments in increasing competition with Japan and India. But Southeast Asia’s own rapid aging is well underway, compressing its demographic margins and marking it as mere placeholder for its far-larger successor: India, with its youth bulge of half a billion souls. India’s demographic dividend will peak in the 2035–2040 time frame, subsequently yielding to similar dynamics in both the Middle East and Africa, which in combination will offer up a dividend approaching one billion workers.

In the brief, it looks like this:

So, what we’re going to witness with Africa is the final great expression of a cheap-labor demographic dividend, largely overlapping with one unfolding across the Middle East. Between them, as I note, we’re looking at about one billion young people to put to work — or else.

Great quote, this:

Aubrey Hruby, an investor in Africa and an author of “The Next Africa” … said, “After climate change, Africa’s jobs crisis will be a defining challenge of our era.”

So, yes, Africa’s demographic prominence come mid-century and how the world effectively enables its processing in terms of economic development will say a great deal about our global economic future — setting aside for the moment the looming reality that climate change will be VERY trying for Africa this century, thus putting at risk this entire throughline.

The good news:

Most young Africans admire and desire democracy, numerous polls have found.

The bad news: Youth becoming disillusioned with corrupt politics and either running away to Europe or embracing militancy of the sort that is spreading across the Sahel (transition zone from Saharan desert to the rest of the continent’s savanna grasslands and jungle).

Remember: inevitabilities yielding inconceivables.

For this to work, Eurasia’s combined superpowers will need to engage in some North-South integration regarding Africa that, imagined from today’s perspective, would seem fantastic in its ambition.

And yet, given the alternative (vast economic failure across Africa due to climate change, sending vast hordes northward in desperation), these inconceivables will become reality.

I see this secret history as being a very connected puzzle. America lifted Japan and the Tigers, who in turn lifted/enabled/financed China, which now does the same in SE Asia and must eventually do for India (very tricky, given that relationship).

So the world as a whole needs this “secret history” (so dubbed because it’s mostly about demographics versus some “world-beating” economic development model that we consistently spot [e.g., America was going to rule forever with its big-firm capitalism, then Japan was going to with its industrial policy, then China …]) to continue successfully unfolding, with the latest being so integrated in global value chains thereupon investing it forward to the region next up in experiencing that demo dividend.

So, again, we need China to work both SEAsia and India, and then India to work both the Middle East and Africa — while China succumbs to rapid aging.

Looking at it that way, you get my argument that India’s rise is the key superpower variable of this century, particularly as it endures climate change’s devastating impact on its labor-intensive ag sector (45% of its workforce).

So, when I look at Africa’s world-record youth bulge heading into demographic dividend status come mid-century, I am seeing India playing the lead role in actualizing that integration into global value chains, outpacing what will inevitably be a slowing effort by China as it ages and starts to more resemble Japan than any “Asian future.” Right now, the African diaspora (emigrants living abroad) are the leading investment force across the continent via remittances. That will not be enough for what needs to happen — particularly in infrastructure.

So ask yourself, Mr. and Mrs. Westerner: Do you really want to see China’s Belt and Road Initiative fail across the continent? Are you prepared to pick up that aid bill any time soon? Because India is not yet there to supplant China, rest assured.

So keep an eye on this brilliant bit of sensible projecting in this series by NYT.

We will see these articles more and more over the coming years. My only admonition is to keep in mind the sequencing here, because it matters. If America sabotages China’s rise from cheap manufacturing to IP powerhouse, then that endangers its ability to finance and integrate India’s processing of its demo dividend, which then threatens what must become India’s replication of China’s “rise” to something far and beyond mere cheap manufacturer as it moves up the production ladder and thus feels compelled to pull Africa into its global value chains.

It all connects and it all matters.

So, when I argue against fighting China’s rise, I’m thinking of India’s rise — and later on Africa’s rise. The West is not in any position to displace these pillars in this sequencing — far from it.

So, as we fret about superpower competitions, let’s keep the entire game board in mind and just not the players.

I know it is tempting to think our future is all about how Ukraine and Palestine and Taiwan turn out, but, with the entire game board experiencing these profound levels of structural change, it is essential we retain the broader perspective.

Future generations are depending on it.

That is a very good question, one that likely requires a very complex answer.

I got nothing off the top of my head, but I will keep it in mind in my ongoing research. I suspect it would be quite different from past experience.

From your perch: any idea how “industrialization” would manifest in western, eastern, and southern Africa that takes climate change and environmental conservation into account?