There are normal and healthy limits to globalization

And the combination of China's completed rise, the Great Recession, and globalization's digitalization all factor into that new normal

Note: today’s newsletter is the last free weekday edition as I shift over to subscription-based access tomorrow

Here I am leveraging a Financial Times analysis of an updated think-tank report. The original report was from the Peterson Insitute of International Economics (PIIE) and was called “Trade Hyperglobalization and its Future” (Subramanian and Kessler 2013). Those two authors plus a third have now updated and expanded their argument about a “trade hyperglobalization” that unfolded across the 1990s and 2000s but then was altered/halted by the Great Recession. I read the updated report and it’s a bit technical, so I’m going mostly with the FT’s analysis.

This whole package of analysis tracks well with what I wrote in America’s New Map: basically, globalization maxed out on globe-spanning East-West integration across the post-Cold War era thanks to China’s rise and the incredible wage differential offered in its surging manufacturing sector that, by extension, was leveraging a substantial-but-one-time-only demographic dividend. Here’s how I summarized it in the book:

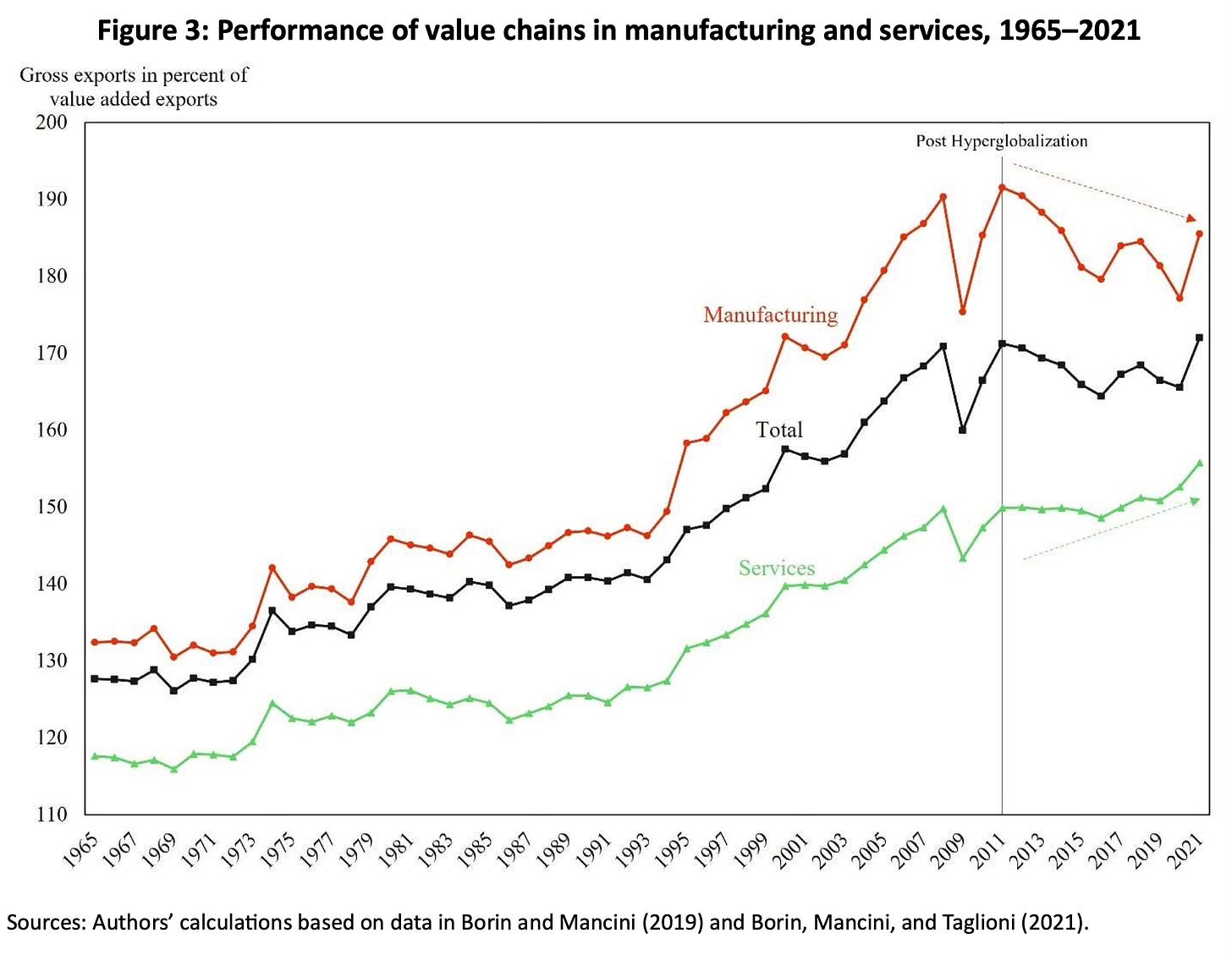

The globalization of the 1990s and 2000s was a goods-intensive phenomenon, which, since the Great Recession, has flatlined. Today’s globalization, rising phoenixlike from the ashes of that worldwide financial crash, features service-intensive trade with exponentially expanding data flows. Global data flows were negligible at the turn of the century. Per the McKinsey Global Institute, they now account for more value added to global GDP than do traded goods—the effective digitalization of globalization. Remember that the next time some pundit declares globalization dead and buried.

In the decade surrounding the 2008 crash, cross-border data flows and cross-border bandwidth-in-use jumped forty-five-fold. If the previous era’s globalization leveraged cheap transportation, then this one capitalizes on cheap communications. Every global transaction today contains digital content, even as we do not yet possess good methods for measuring data flows—much less policing them.

The economic drivers behind globalization’s transformation from goods-centric to service-centric make clear that we are in a period of globalization’s intraregional consolidation …Point being all these consolidating trends are a logical, system-wide response to the emergence of a global middle class located overwhelmingly in emerging markets, which, until recently, lacked the infrastructure—both physical and virtual—for these levels of consumption. No economic law states value chains must always be world-spanning to constitute “real” globalization. If anything, business logic argues for supply chains to be no longer than necessary to efficiently serve any market. That is the “de-globalization” we witness today: the emergence of more efficiently regionalized value chains to serve new demand centers—China chief among them.

Again, what I'm asking is that we recognize that the peak or “hyper” globalization period of the 1990s and 2000s was both a unique and positive affair marked by China’s rise — something now many of us in the US fear because of the competitive pressures that have arisen as a result. Now that China has slowed down to more advanced-economy levels of growth, many in the West are simultaneously celebrating its come-down (aha!) while fearing what that means (slower global growth for all).

So, understand, we have three big things happening here:

Hyperglobalization as represented by China’s rise has ended for all sorts of natural reasons, the biggest being China now anchors its own global demand center in East Asia and hence increasingly shifts from factory floor to the global economy to factor floor for the Asian demand hub.

That leads to the rational reregionalization/optimization of global supply chains that we’re witnessing now and which are reflective of the mercantilist mindset of the West’s current bout of economic nationalism (hence all the globalization-is-dead crowing).

But globalization is likewise radically evolving thanks to its ever-more-pervasive digitalization, much of it, I suspect, we have trouble tracking and measuring because it’s so different and new and evolving relative to the old goods-centric global trade we know (and track) so well.

In effect, America is like the toddler in pre-school that has a hard time transitioning from one activity to the next (here, hyper globalization to globalization’s digitalization). As I argue in the book, this is a bit odd considering we’re the global leaders in both digital content creation and world-spanning platforms for delivering it.

Instead of just being happy that globalization’s peak period of the 1990s and 2000s raised up so much of China/Asia from endless poverty to membership in an ascendant global majority middle class, we in the US choose now to demonize China and globalization as the source of all our woes.

What should we be doing instead? Retooling for the next competitive landscape, which I argue in my book is increasingly cyber-centric and involves networking, surveilling (yes), and successfully capturing the hearts and minds (stomachs and wallets) of that emergent, Global-South-centric majority middle class that is leaving behind its past and embracing, for the first time, a universe of processed, packaged, and branded goods. Thus, winning them over to all manner of brands — to include political and national brands — is how a superpower economy grows with globalization this century in addition to amassing the sort of big data flows that will drive the advance of AI in its predictive capabilities. Winning the superpower brand wars over that global middle class determines which superpowers prevail in all manner of domains (ideological, political, technological, economic, security, social).

We’re in a race to access that global middle class, win its brand allegiance and by doing so capture all that data to elevate our technological capacities to serve and win them over even more, thus ensuring our nation’s long-term economic health and the prevalence of our pluralistic values. The Global South, bedeviled as it will be by climate change, is not a burden nor an obligation but the prize and the opportunity — precisely because it will be put in such play by climate change’s discombobulating impact.

This growing awareness, clearly on display among our competitors (EU, Russia, China, India), is lacking in America right now. We are stuck in our East-West mindset while our competitors are shifting to a North-South mindset for all the reasons argued here. America can fear all that effort, label it with all sorts of scary titles, and seek to “contain” it. But, until we offer the Global South some better model of belonging, China’s quick-and-dirty offering (Belt and Road Initiative with a 5G/Safe City upsell) will continue to win over most of the world.

Having got that off my chest, let’s dive into the FT article analyzing the updated think-tank report on “hyperglobalization” (or hyperglobalisation as the Brits render it).

The opening:

Death notices for the surge in globalisation that started in the 1990s have been posted for about as long as the process itself. Covid-19, the US-China conflict, climate change and the struggle for green industrial supremacy are all being offered as reasons for globalisation coming to a stop. And yet it moves.

Now, it’s true that the era of “hyperglobalisation” from roughly 1992 to 2008, where trade grew markedly faster than global gross domestic product, is over …

Yet on close examination it appears some of the positive parts of globalisation have either slowed naturally or are still in train, and what has gone into reverse wasn’t much of a loss. There are some serious challenges ahead in navigating macroeconomic shocks, particularly in China, and always the risk that geopolitical tensions will escalate rapidly. But only those who fetishise the internationalisation of an ever-larger share of activity in every conceivable economic sector need worry much about what’s happened so far. [emphasis mine]

Globally, goods trade relative to GDP has flatlined or shrunk a little since the financial crisis in 2008. Services trade is still rising as a share of GDP, though at a slower rate than before, and in any case the numbers are distorted by inaccurate reporting for tax avoidance purposes.

But, as the study notes, the remarkable development isn’t that goods trade is slowing but that it’s remained as strong as it has. It has faced stiff headwinds, but they are more to do with the evolution of the world’s economies than with shocks such as Covid or meddling governments.

For one, the process of labour-cost arbitrage — rich countries sourcing from lower-income economies — has somewhat run out of space, at least in those countries (such as China) where good infrastructure has connected low-cost workers to global value networks. (There’s a lot more that could be done in countries like India, but poor infrastructure and business climate have held them back.) That’s a good outcome to be celebrated. Trade in goods postwar has played such a big part in reducing global inequality that there are fewer poor workers left for it to liberate.

That’s a great summary of what I’ve been trying to say here: there are natural limits and evolutions to globalization that we consistently treat as “disasters” and “chaos” and “existential threats” and so on, when, in truth, it’s simply globalization’s rather natural evolution as major players within its ranks likewise evolve and co-evolve.

[NOTE: tomorrow I will explore a great example of that evolution in line with my book’s argument that to track globalization’s center of gravity is merely to follow the bouncing ball that is the sequential unfolding of demographic dividends region-by-region.]

From the FT article’s end:

The integration of world markets in goods, services, capital, data and people is not something to be pursued at all costs. It is a means to an end. For 30 years, goods and services trade have promoted prosperity, including creating and (admittedly imperfectly) disseminating technologies to improve lives. Managed properly, it can help do the same to combat climate change. Globalisation has certainly not failed. Nor, for the moment, has it hit a wall. It is evolving, partly in response to the changes wrought by its own success. [emphasis mine] The much-hyped era of hyperglobalisation has faded, but solid gains are still being made.

That is such a validating bingo to me. Some people out there actually get it, and, not only get it but can make intellectual space within their thinking to address climate change as the next great evolutionary factor in globalization’s continued unfolding.

I realize my book is a tough sell right now. It’s not focused on the US political scene (i.e., Trump), which eats up so much media and intellectual attention. It’s also not a doom-driven screed, which is very popular right now as well. We also constructed, in a visual sense, a book that is part graphic novel with those dozens of illustrations, thus forcing us to go with a solid-but-still-seen-as-hybrid publishing house like BenBella, making our achievement of visibility all the more harder in the world of Big Publishing.

Those are all complications but none are show-stoppers, not when I come across validating analysis like this — leveraging serious scholarship and data-crunching — that fires up my confidence regarding the book’s intrinsic logic.

There are sensible and feasible pathways out there to be forged and widened. We just need to keep coming up with, and disseminating, positive storylines regarding their discovery and eventual completion.

To top off, see this from the end of the think tank article:

The truth is just ideas going in and out of fashion, as Robert Solow famously said. Today the vanes of taste have veered in favor of inwardness masquerading as a legitimate response to the excesses of neoliberalism. But this trend too shall pass, not least because the era of hyperglobalization was also the golden age of poverty reduction and income convergence for developing countries—a point they should reiterate. The disenchantment with globalization and the embrace of inwardness are, in their own way, forms of intellectual neo-imperialism.

In other words, the North is pulling the same bullshit it always pulls when asked by the South to consider reshaping the global economy more equitably. We saw it with the Group of 77/Non-Aligned Movement’s call for a New International Economic Order (NIEO) in the 1970s and we’re witnessing the same selfish and short-sighted reaction today with regard to the looming threat of climate change.

Thus, our good fight continues …