Africa's demographic/climatic collision

Tunisia exemplifying Africa's challenges of "rising" amidst climate change

The Christian Science Monitor (where I scored my first-ever published article in 1989!) put out this excellent piece that transmits — at a very human level — how climate change is already stressing out lower latitudes (here, Tunisia in North Africa).

The basic message: there is an exodus unfolding in Tunisia and a great deal of it is climate driven.

Tunisia, you may recall, was a big early part of the Arab Spring in 2011. The dream for many young rural men back then was the opportunity to farm with — hopefully — more support from the government than had previously been offered by a longstanding dictatorship that focused its corrupt attention on coastal cities versus the rural interior.

The environmental problem that subsequently emerged made that dream impossible across Tunisia: it stopped raining and these farms are overwhelmingly rain-fed.

The story of one man — Barqoushi:

The first setback came in 2014 when the rains stopped. His barley and wheat dried up, forcing him to purchase animal feed for his flock. After two years of rising feed prices, he was forced to sell off his sheep. By 2017, his vegetables were requiring year-round irrigation, costing more than $450 dinars, about $150, per month, and production was halved. After trying his hand at low-paying jobs in the village, scraping $8 a day, he decided he needed to leave his home, farm, wife, and children to relocate to the capital, Tunis, 125 miles away. He works as a construction day laborer painting buildings. On a good day, he earns $16 for 10 hours of work.

Classic move. Dad heads to the city and tries to make some money to pursue a non-trivial solution: a deep well that would feed his crops but which lies beyond his capital to enact.

If only he could tap the receding underground aquifer, he says, he could make his farm thrive.

“I wouldn’t leave my home for a single day if I had water. All I need is a well,” he says, shaking his head. “If I only had a well.”

At the current rate, it would take Mr. Barqoushi over a decade to save up the $10,000 needed to dig a 100-meter (330-foot) well.

So, there’s the impasse, or the kind of thing that foreign aid can often fix (digging wells is a biggie also for the US military when it seeks to do good deeds wherever it is situated). It just ain’t happening here, and even if it was, you have to wonder about the sustainability of it.

The CSM story argues that a trio of crises drives migration patterns today: political instability, economic inequality, and climate change. But those three are hard to dis-entangle, as the piece readily admits.

Climate change decimates the farming/rural sector, exacerbating urban-rural economic inequality. That pushes men like Barqoushi to head into the city, flooding that environment with ultra-cheap and desperate labor. That situation feeds political instability.

If Barqoushi has his rain or his well, things would be different all around.

UN stats bear out this causal-chain diagnosis:

The share of refugees and asylum-seekers from regions threatened by climate change, for instance, has jumped from 61% in 2010 to 84% in 2022, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

Tunisia, like most of the Mediterranean rim, is suffering greatly from climate change. Most climate experts will tell you that this region is particularly vulnerable.

The Med Rim is warming at a rate approximately 20% faster than the global average, with annual mean temperatures now already about 1.5°C above late 19th-century levels — so a leading edge situation. By the end of the 21st century, regional temperatures are slated to rise by about another 4 degrees Celsius.

It’s that sort of inevitability that sees a couple of Australias’ worth of livable/arable land disappear across my Middle Earth band (30 degrees north and south of the equator) and magically appear across the planet’s northern quartile — unfair in the extreme, but there you have it.

Water scarcity is a longstanding issue across the Mediterranean basin and that, of course, is being exacerbated by climate change to the tune of a 10-30% loss of precipitation over the coming years/decades. Meanwhile, as currently populated and farmed and urbanized, the Med Rim is expected to require 2-3 times more water by mid-century.

Not realistic, so depopulation will ensue.

Toss in all the coastal zones subject to rising sea levels, saltwater intrusion, and warmer sea temps and we’re talking about a fisheries industry under severe strain already.

Back to the CSM story:

In few places can one observe this collision [of negative trends] as clearly as in Tunisia. Here, in this Mediterranean African country, people are experiencing the autocratic relapse of the world’s youngest democracy, hyperinflation thanks to decades-old economic mismanagement, and temperatures warming at twice the global rate, coupled with historic drought.

This is why I argue for North-South integration along as many lines as possible: Tunisia ain’t making it on its own. It is failing now as a state and it will only get worse as climate change deepens its impact. The EU either reaches down across the Mediterranean and offers some sort of belonging in a North-South construct (however defined or extended) or it’s got a huge, flaming disaster on its water border.

Remember: it was thinking ahead on Russia that pushed NATO and the EU to pull in those Eastern European states as quickly as they could in the early post-Cold War period. And, yeah, it was a smart move to anticipate that inevitability of renewed Russian aggression.

That effort at eastward integration helped make the EU the economic beast it is today in terms of overall size and consumption and productive capacity. The Union has its problems and challenges alright, but having more to work with helps, as does limiting the proximity of the threat from Moscow.

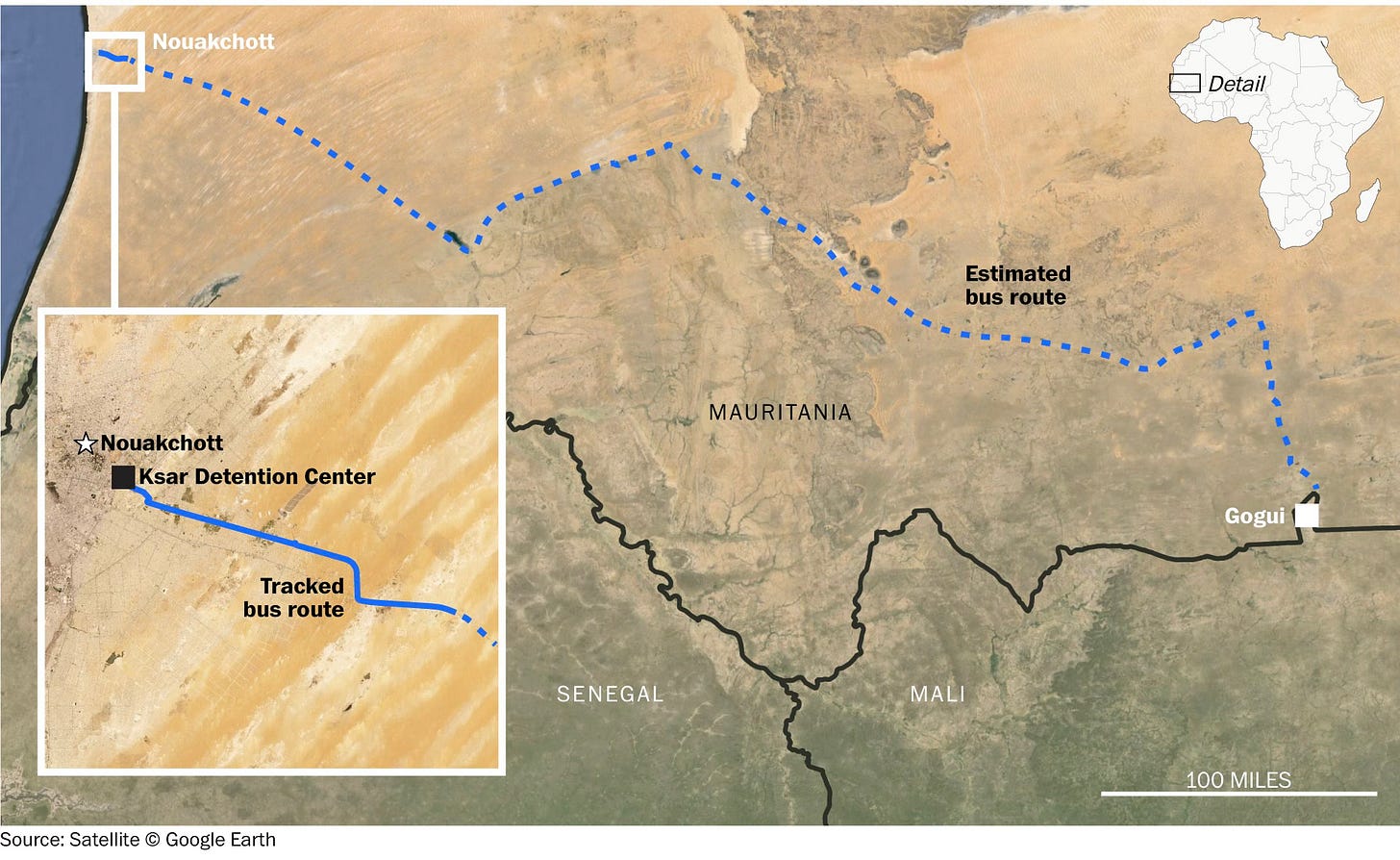

The same logic applies to North Africa with regard to climate change. Isn’t it better to extend the EU’s boundaries southward versus having that problem right on its shore, coming across in a never-ending stream of boats. We’ve already seen the EU being caught paying off North African governments to intercept climate migrants heading to the Mediterranean, the deal being that the local governments take the refugees into the interior desert and basically dump them.

WAPO: With Europe’s support, North African nations push migrants to the desert

Dirty deeds, done dirt cheap.

Again, the projections going forward are grim (per the CSM piece):

“Tunisia is not an anomaly by any means, globally or within the region,” says Brendan Kelly, head of the migration and development unit at the International Organization for Migration in Tunisia. He cites the country’s water stress, more frequent and longer heat waves, a drop in precipitation – which is expected to drop 10% to 35% further by 2050 – and lack of economic opportunity pushing more and more Tunisians to leave their hometowns and villages.

“In Tunisia we are already seeing [how] the extremely serious consequences of climate change and environmental degradation, combined with economic factors, drive human mobility,” he says. “The projections for the next decades to come are even more serious.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.