I have praised Our World in Data in the past and am happy to use this post to reiterate my profound admiration for how the group visualizes long-term global trends. Their analytic products are almost always very powerfully delivered.

The Oxford-based academic who founded OWID and writes a lot of its summarizing online articles is Max Roser. His philosophy is beautifully balanced:

The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better. All three statements are true at the same time.

The man and his people are doing God’s work, in my opinion.

Now, in this NYT op-ed, Roser gets more ambitious. It’s one thing to celebrate the profound decline in the share of the global population living in extreme poverty; it’s another to argue we need to raise our definitions of making it in our global economy.

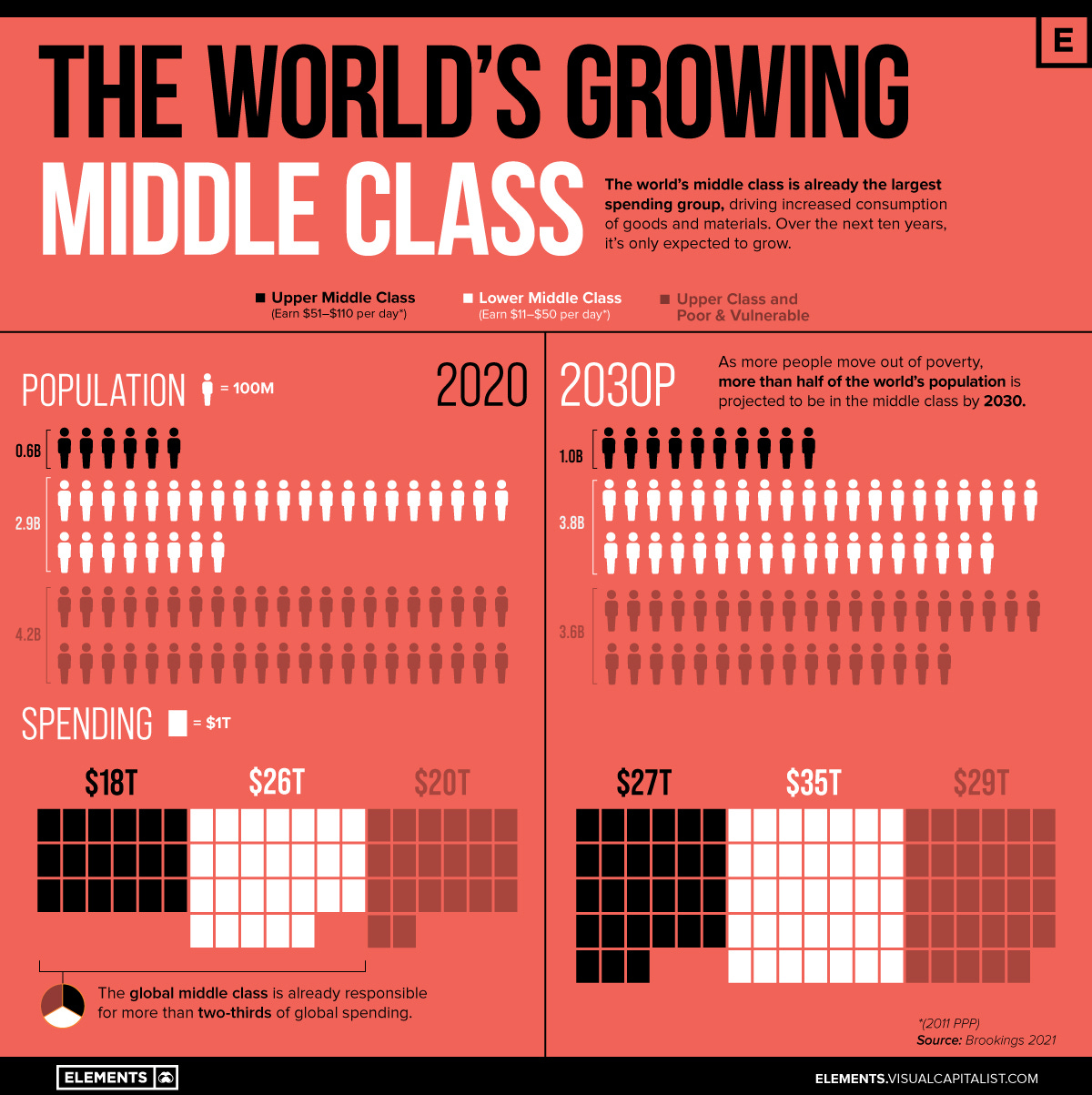

Roser’s argument here does undercut those estimates that I love to tout about an emergent majority global middle class. For example, here’s Visual Capitalist’s recent depiction:

But notice the definition of that expanding middle: earning between 11-to-50$ per day.

That’s where Roser seeks something better, and his instincts — if we want this emergent majority middle class-and-higher pool to rule itself versus succumbing to radical rule from either the Left or Right — are spot-on. The middle class really arrives in a nation, I would argue, when it is large enough to rule itself within a pluralistic polity. That happens when the bulk of your population has enough income and wealth to start demanding the long-term protection of both by the state.

So, what Roser argues is that we need to raise that lower bar from $10/day to something more like $30/day, or — in effect — from the minimum rate that globalization has managed to hit to-date to something better over the long haul.

This is the right sort of ambition, and redefinitions of class and consumption must be pursued to make it happen. All of that fits my larger prescription of a much-needed progressive era for the global economy as a whole (but America in particular).

Here’s how Roser argues his point:

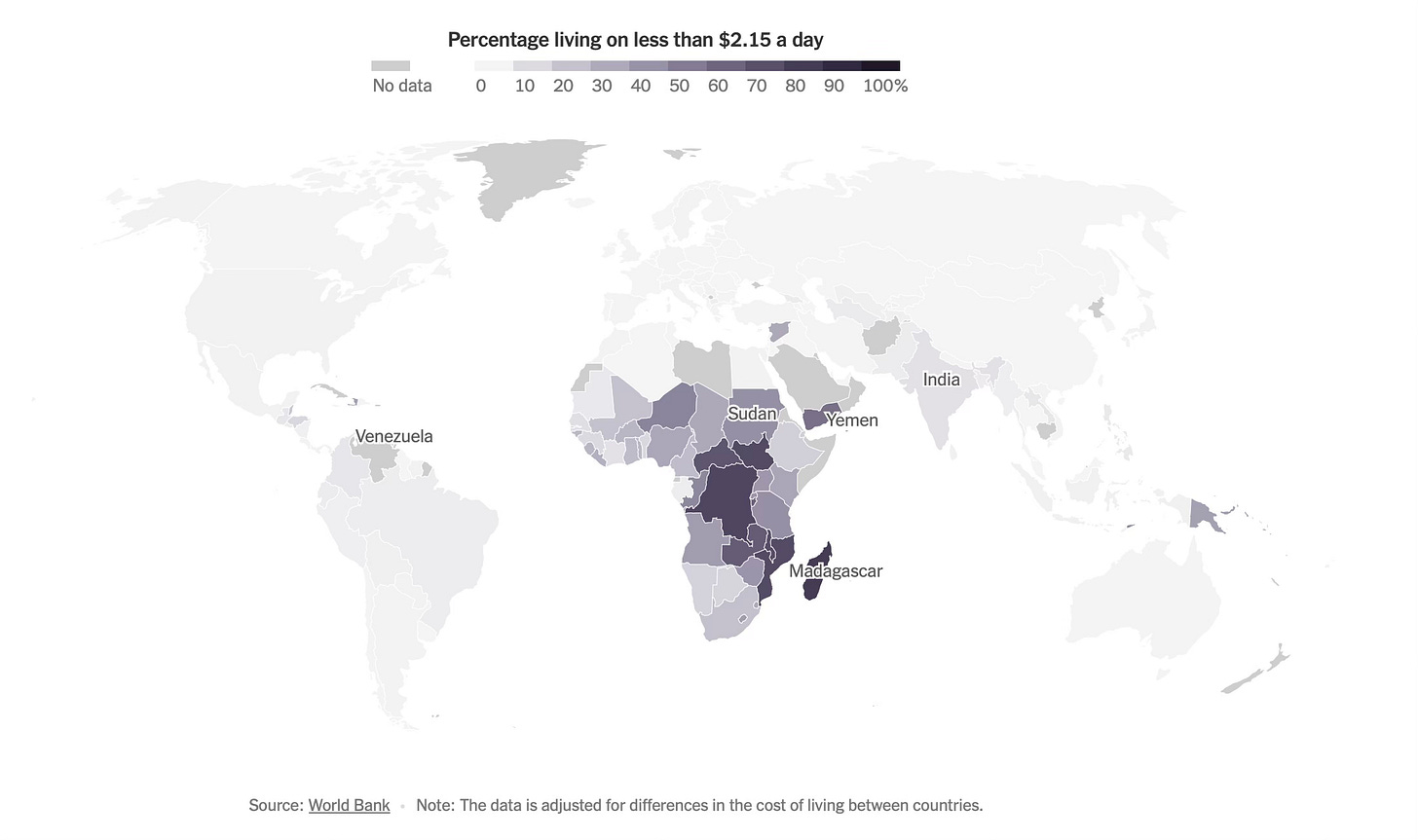

The international poverty line, which the U.N. uses to measure global poverty, is very low. It tells us how many people live on less than $2.15 per day. This low poverty line reveals that a large number of people continue to live on extremely little, as the map below shows. Seventy-three percent of people in Mozambique live in extreme poverty; in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it is 75 percent. The international poverty line is valuable because it has succeeded in drawing the world’s attention to the extreme poverty of the world’s very poorest people.

Now, understand that Roser’s definition of a “large number of people” here is but one-tenth of the world’s population — the lowest share of extreme poverty that our world has ever seen.

But, again, this is an argument about doing even better by raising the bar. We’ve done that, for example, in our definitions of war, which most researchers now peg as low as just three deaths/day over a year (1,000 or more combat deaths = lowest threshold of a recognized “war”). Yes, that’s crazy low compared to the past, but that bare minimum threshold doesn’t exactly equate to sufficient security of the sort we associate with a middle class existence in the West, now does it?

So, it comes down to whether we measure poverty from the perspective of the world’s impoverished looking up optimistically (I need at least that!) or from that of the North’s middle class looking down pessimistically (I am not going back to that!).

I get that: if you want a truly functioning middle class that makes reasonable demands on the political system, it makes more sense to go with the middle class’s sense of fear than the underclass’s sense of relief.

Back to Roser:

The misuse of low poverty lines as a criterion for what is sufficient for a good life distorts our perception of people’s living conditions. The reality is that we live in a world in which billions are struggling to pay for the bare necessities: Three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet. Three and a half billion do not have access to sanitation facilities. Most of them live on more than two or three dollars a day, but they are still living in deep material destitution. To claim that they can live “a life of dignity and opportunity” I find ethically repulsive. It negates the misery of billions.

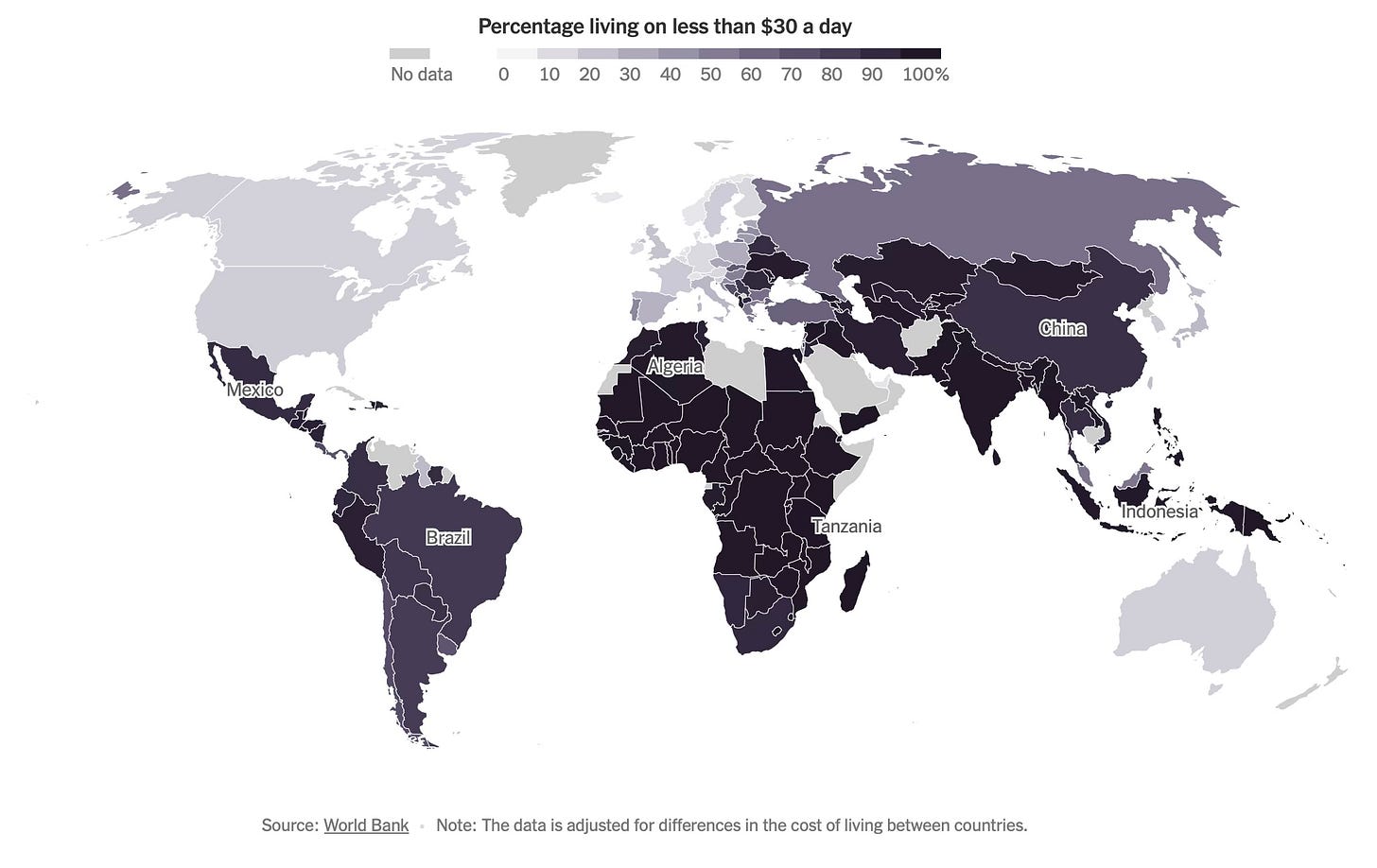

As Roser points out, the UN set the low end of above-$10-a-day based on measuring poverty in a lot of poor countries, whereas he proposes to establish a similar criteria but by measuring poverty in rich countries. On this basis, he argues for a $30/day redefinition of making it in a middle class way (not just the existence of some discretionary income [i.e., that income not automatically dedicated to the bare necessities of life] but sufficient discretionary spending to achieve some genuine economic autonomy).

And yes, dignity and autonomy go together on just about everything.

So, when Roser raises the bar that high, we get a very different map:

In effect, then, Roser is seeking to define globalization’s essential threshold for universal basic income (UBI) from the perspective of an advanced economy — the lifestyle line below which any reasonable, empathetic person would assume nobody should have to tumble because they themselves view it as an unacceptable plight, or one that invariably drives such masses to seek out extreme political solutions from either the Left or Right.

Fair enough.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.