When rising oceans means less freshwater

Climate change threatens to "intrude" into New Orleans's water supply -- in large part due to upstream droughts also triggered by climate change

Water is everywhere on this planet, but so little of it is drinkable. From America’s New Map:

On Earth, the water that humanity sustainably consumes is but a tiny fraction of the world’s total supply, 97 percent of which resides in the oceans as salt water. Outside of desalinization (which is getting less expensive but remains energy intensive), that leaves 3 percent as fresh water, two-thirds of which is frozen on Greenland and Antarctica. Humanity makes do with that remaining single percent …

Of that tiny renewable freshwater share, three-quarters goes into agriculture while a tenth goes into industry, leaving about 15 percent for direct human consumption. What comes through our pipes and faucets is thus a mere one-sixth of 1 percent of the world’s water—our most precious natural resource now being globally redirected and redistributed by climate change.

Like with much of climate change, the impact favors the North and beggars the South, as water-poor lower latitudes tend to get drier while the water-rich higher latitudes get wetter. Having said that, both higher and lower latitudes are going to see rainfall unfold more sporadically: periods of drought interrupted by torrential downpours.

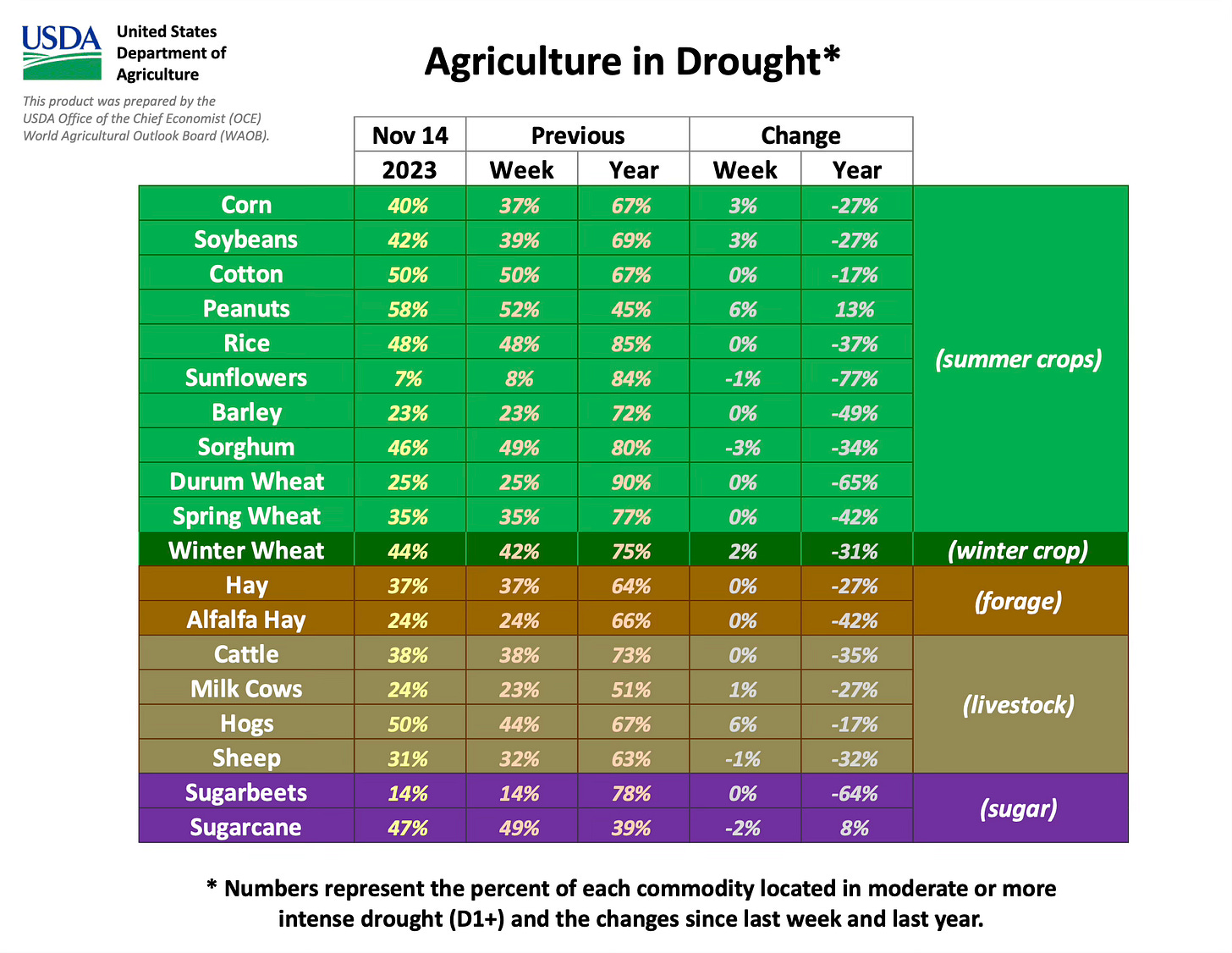

That volatility complicates agriculture. Check out the chart displaying how much of current US crops are endangered by drought right now. That pressure forces farmers to draw upon irrigation more, reducing normal riverine flows to be sure.

And this is a pretty good year overall …

Here we have a NYT story illustrative of such complex causality, one comprising drought and rising sea levels combining to threaten New Orleans’ water system through saltwater intrusion. Here’s how I summarized the latter dynamic in my book:

Rising saltwater sea levels paradoxically increases water insecurity by ruining coastal freshwater aquifers. This intrusion used to happen only with storm surges but now regularly unfolds as “sunny day floods” reflecting high tide.

With sea levels set to rise along US coasts by one foot come 2050, Americans are looking at a doubling of flood events within the current thirty-year home mortgage window. That will surely trigger huge public infrastructure costs.

For New Orleans’ Sewerage and Water Board, they’re looking at a $200 million bill to upgrade their water treatment plants to remove the added salinity.

We’ve already witnessed the four horsemen of the Anthropocene (Gaia Vince’s designation of heat, fire, flood, and drought — see her Nomad Century) scare insurance companies out of Florida and California, creating a direct impact on people’s PITI (principal, interest, taxes, insurance) monthly mortgage payment. Here, we see your local taxes and water bill being not just hiked but the latter potentially knocked out of commission on a regular basis.

From the NYT story, this form of intrusion involves sea water penetrating up the Mississippi, thus ruining the freshwater that local communities draw from it:

All through a sweltering Louisiana summer and into the fall, people in Ms. Pete’s corner of Plaquemines Parish, a marshy strip of land southeast of New Orleans dominated by fishing and the oil industry, endured salty showers and avoided drinking from the tap. Their water comes from the Mississippi River, which runs through the parish like a central nerve.

But this year, droughts in the Midwest sapped the thousands of tributaries that supply the Mississippi, weakening the river and allowing a wedge of saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico to creep dozens of miles upstream …

Forecasts showed that the salt could reach treatment plants in New Orleans by late fall, contaminating the drinking water for hundreds of thousands of people and possibly leaching dangerous materials, including lead, from the city’s aging pipes.

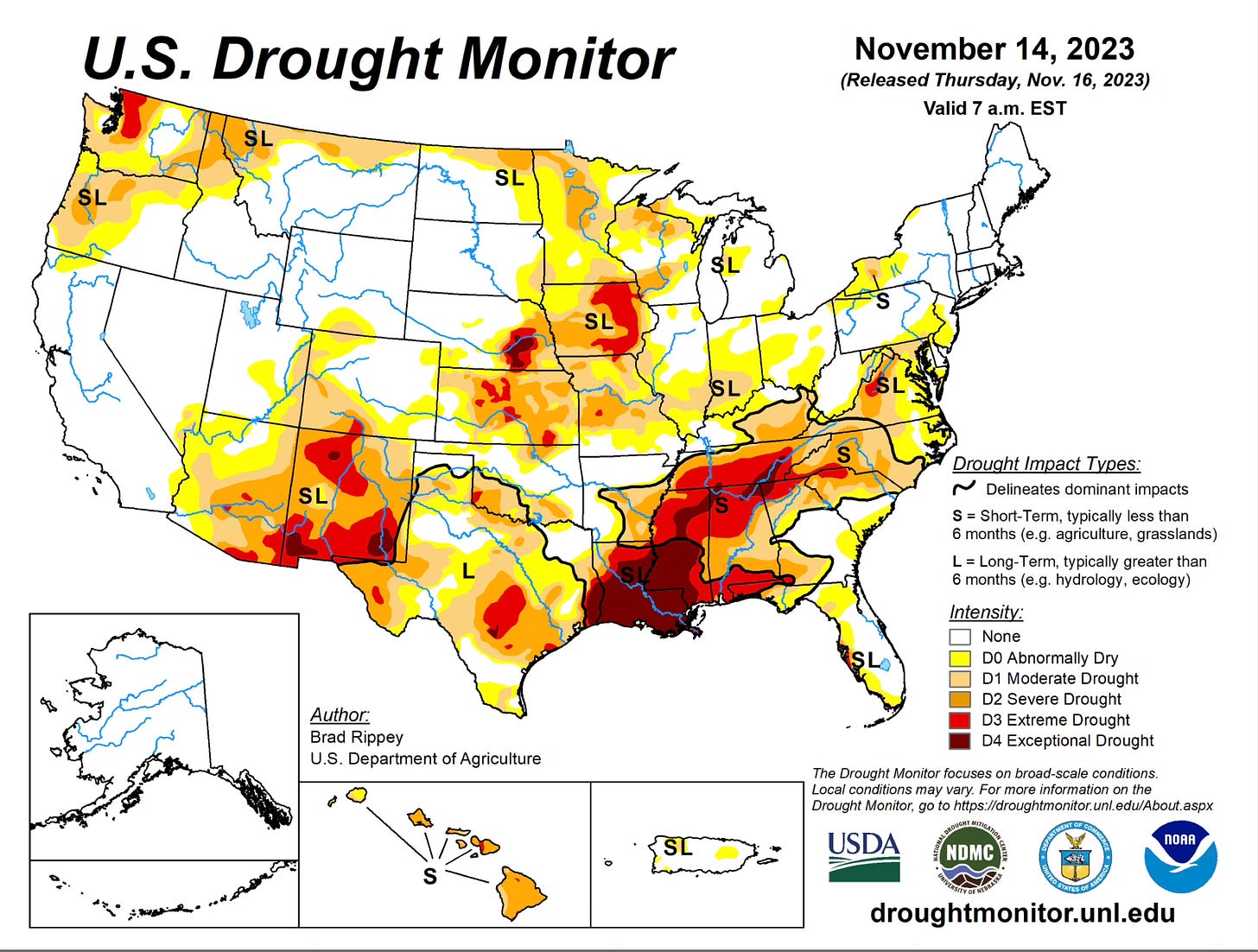

And it’s not just the Mississippi being weakened. Check out just how dry Louisiana is relative to the rest of the country right now.

It’s almost like all the upriver droughts are being carried down and concentrated at the river’s terminus.

So it’s basically the case where a drought-weakened Mississippi is no longer able to maintain enough pressure and sheer presence to keep the rising salt water at bay (pun intended), allowing that salt wedge to invade northward dozens of miles. That gives you a sense of the complexity of the problem here, as New Orleans is getting this problem from both ends — upstream and downstream.

This problem is only going to get worse:

Saltwater from rising seas, a growing threat to freshwater worldwide, has plagued southeastern Louisiana before. But this was the second year in a row that the region suffered a drinking water crisis, and experts predict more frequent intrusions as climate change continues to cause shifts in Midwestern rainfall.

And when the Army Corps of Engineers come in to dredge the river threatened by lower rainfall? Their actions tend to make it easier for this intrusion to unfold. As I point out in the book, droughts can basically shut down riverine commerce, something that’s happening with more regularity now along the Mississippi (2013, 2022).

Then there’s just the everyday hardships imposed upon the public by all this:

The region experienced an epidemic of busted water heaters and rusted dishwashers. Residents worried over smelly faucets and odd rashes, and they rushed to the fire station every time local officials dropped off cases of bottled water — which they used to rinse their hair, feed their pets and make their coffee and sweet tea.

So, no surprise, it wears on people — even longtime residents. One 59-year-old readily admitted to the NYT reporter: “With the environmental stuff that’s changing around us, we don’t know how long we’re going to be here.”

Adapt, move, or die. That’s the choice all species face with climate change. Humans can surely adapt all they want. The question is the money and — in many cases — the increasingly futility.