When Rising Powers Operate Overseas Ports: Natural Supply-Chain Management or Threat to US Order?

India starts down a supply-chain management strategy that China has pursued for years

Two stories got me thinking about this:

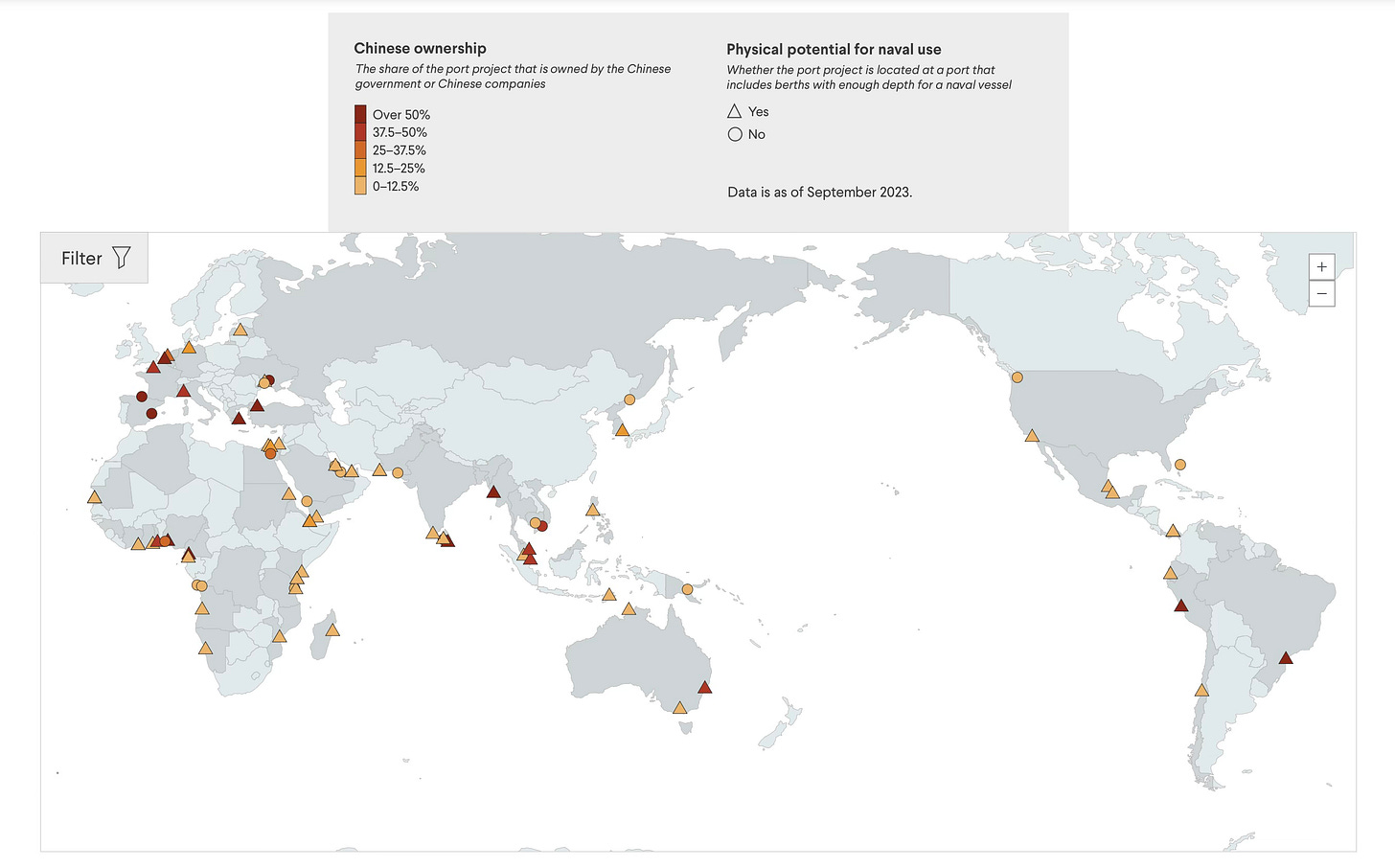

This is nothing new for China, as Chinese state-owned companies like COSCO Shipping and China Merchants Group have invested in, or operate terminals at, nearly 100 ports across over 60 countries spanning all continents except Antarctica.

Who owned these ports prior? Typically local firms.

What does China do?

It comes in with big plans to expand port operations (yay!), often financing a great deal of it with loans to the local government (not so yay!).

Here’s how I described the process in America’s New Map:

The biggest advanced-economy gripe against China’s BRI “investments” focuses on the fact that the vast majority are really loans (versus grants or official development assistance) that, when an economic downturn arrives, effectively “trap” the recipient under a mountain of sovereign debt that Beijing exploits by (a) locking in repayment as long-term, below-market resource flows to China; or (b) assuming operational control of the collateral via decades-long leases (consider, for example, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port). While such arguments presume that BRI participants are not savvy enough to negotiate on their own behalf, such opportunistic collateralization effectively shifts project risk from Beijing to its partners. Already, several dozen BRI partners owe China sovereign debt greater than one-tenth of their annual GDP. To critics, that is Beijing’s debt-trap diplomacy at work—highlighted by indebted Sri Lanka’s political and economic collapse in 2022.

Still, on the far side of any such experience, a country tends to have a radically expanded port capacity. It’s just that China wants that operational control in return for its investments (such as they are).

Still, from the West’s perspective (here, quoting a WAPO story):

The majority of the investments have been made by companies owned by the Chinese government, effectively making Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party the biggest operator of the ports that lie at the heart of global supply chains.

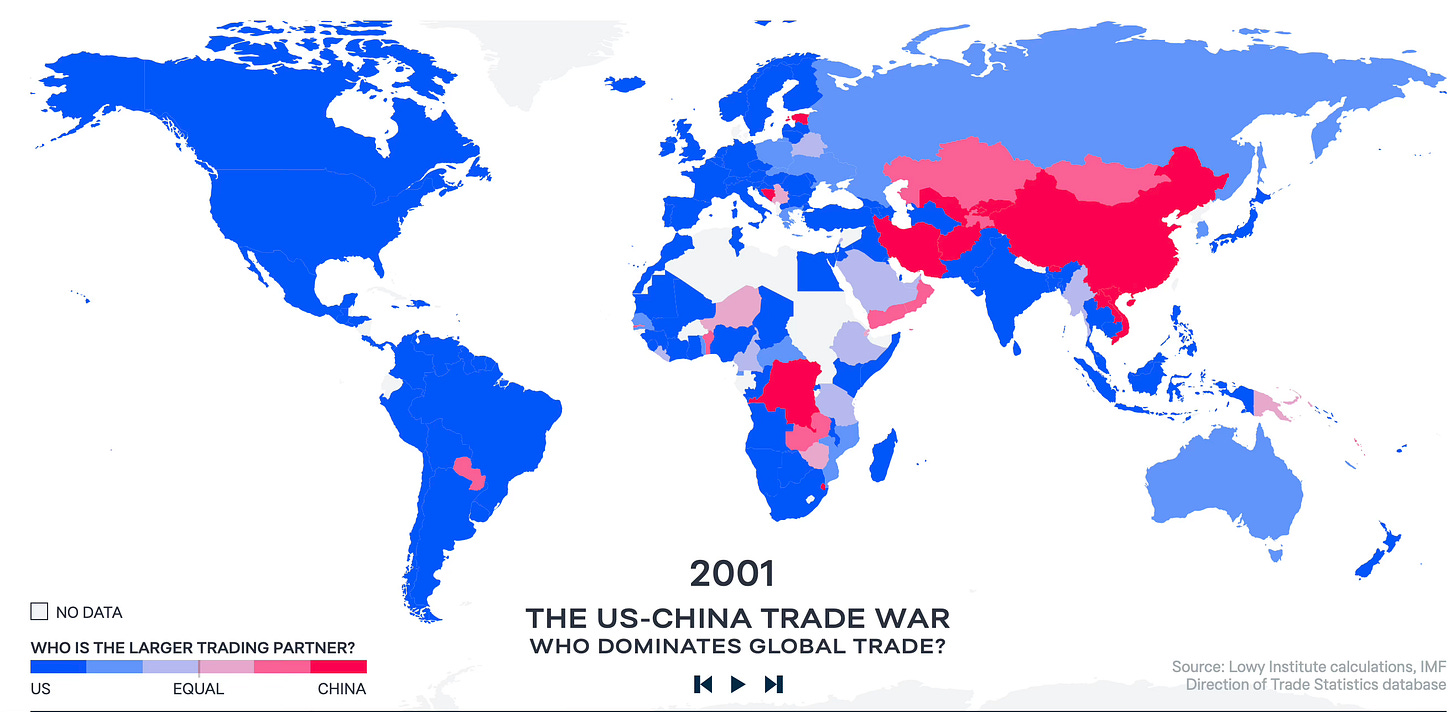

Given China’s preeminent role in global trade, that’s not so weird.

I mean, check out how many states featured the US as their primary trade partner at the beginning of this century — relative to now:

When you observe (dare I say broad frame?) the issue like that, it seems somewhat predictable. China’s overseas interests have ballooned, and one way they approach that problem is to seek out control — port by port. The flag following trade, yes?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.