Xi's dream: World needs China but China doesn't need world

A specter is haunting Beijing: the specter of a demanding middle class

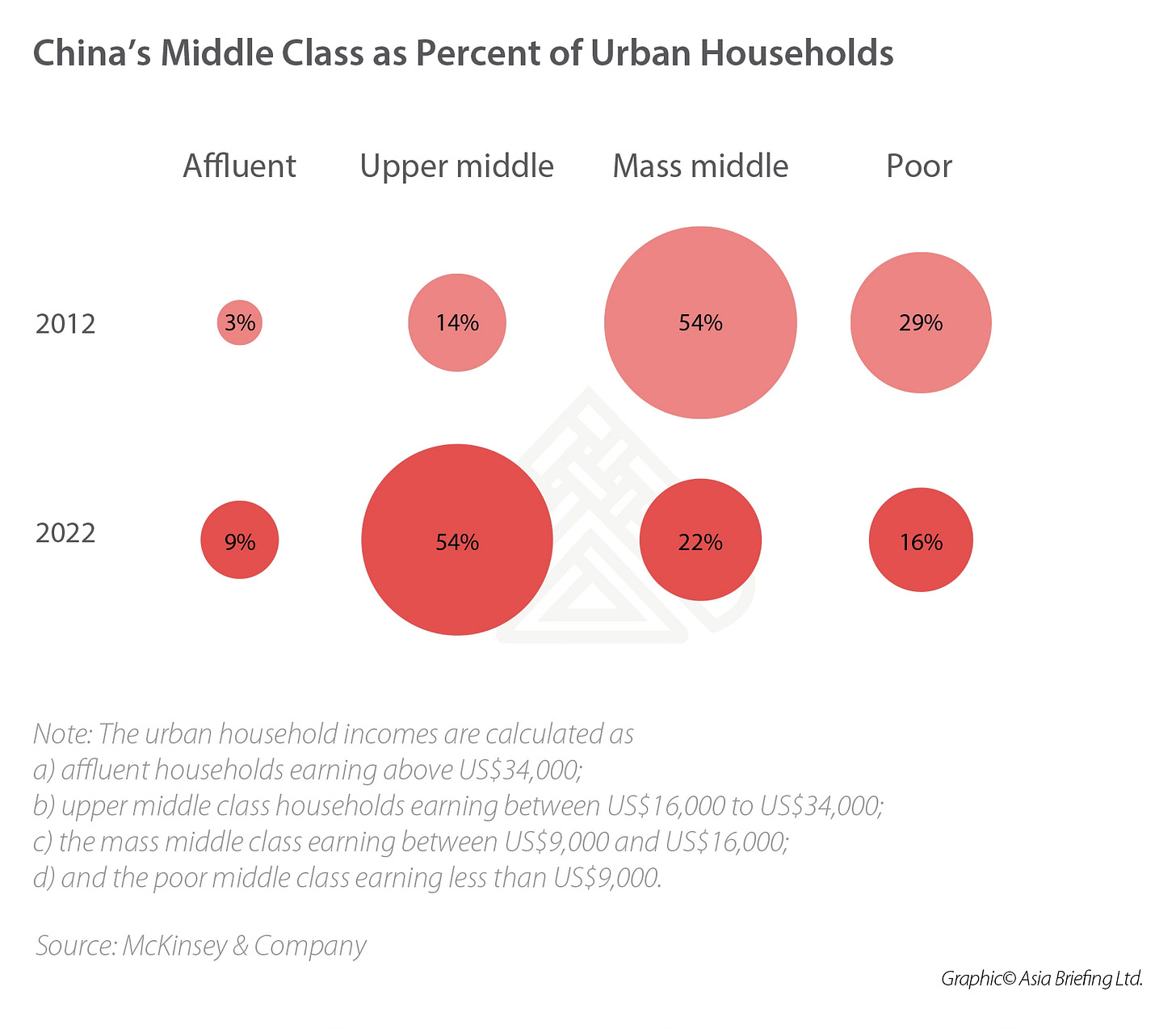

China’s middle class is growing — upward. Back in 2012 the combined middle class was 68% of the population. In 2022 it had risen to 76% while the poor were cut in half. That is serious progress.

But we all know what happens when you get a large middle class in an authoritarian state: those people start wondering why they can’t rule themselves. Being more educated and economically empowered, the middle begins to demand greater political liberties and accountability from the government.

This was the story of both South Korea and Taiwan — two huge bellwethers for the Chinese.

It all comes down to the perception of social mobility: when the middle class feels economically secure, they can stomach and may even prefer the stability provided by authoritarian regimes. But if they perceive a threat to their status or future prospects—such as economic downturns or rising inequality—they may lean towards supporting democratic reforms to ensure better redistribution and political representation. This dynamic creates a trade-off: when feeling vulnerable, the middle class prioritizes democratic change over the stability of the current regime.

Remember my bit:

The poor want protection from their circumstances

The rich want protection from the poor

The middle wants protection from the future.

Countering any natural push toward democratization in China is the reality that so many of its citizens still remember the bad old days under Mao, before Deng stepped up and marketized the economy.

Xi represents the last generation to have come of age during the Cultural Revolution, and, like the Boomers in the US, he clings to power on behalf of that mindset: when it doubt, double down on ideology to maintain social cohesion and party control.

This is why China feels both powerful and stuck right now: it adopted the Japan/Tigers model of export-drive growth under the benevolent umbrella of America’s dual willingness to absorb all those imports while providing the security “glue” for East Asia (keeping that situation clear enough about America’s military superiority there and thus allowing for all to countenance the sequential rise of so many powers in the region over the past several decades).

Think about Asian history: we have never had a situation of such powerful multipolarity: Japan risen, the Tigers risen, China risen, SE Asia rising, India rising. That’s a whole lot of risen/rising that, absent the US security “glue” role, could have easily succumbed at numerous points along the way to some sort of rivalrous conflict.

To-date it hasn’t, and this is one of the most amazing achievements of America in its market-making role across Asia since 1945.

Really amazing.

But the region outgrows our capacity to deliver that sense of security, and, since the 2008 crash, America has purposefully moved away from market-making responsibilities and embraced more me-first market-playing dynamics. This is natural and good and inevitable, but it is also scary (like Trump).

Because, in China’s clear rise, there is a new potential sheriff in town, so to speak, and just about everybody in Asia who’s not Chinese finds that reality unnerving.

Would it all be okay if China succumbed to democracy?

Yeah, actually, that would do it.

But let’s be honest: everybody in Asia who’s not Chinese — and even those who are — find the prospect of that journey to be … even scarier on many levels.

Remember how it went down in South Korea in the late 1980s: lots of Tiananmen Square-like street protests.

Understand: from its founding in 1948, S. Korea was ruled by authoritarian governments, to include military dictatorships. But once the nation’s middle class started to assert itself in the late-1980s, mass protests erupted, demanding democratic reforms and the end of military rule. The movement was driven by various social groups, including students, labor unions, and civic organizations. The protests ultimately pressured the government to concede to demands for democratic elections.

That makes South Korea’s democracy less than four decades old. It also means it took four decades for that evolution to come to fruition, driven by economic advance.

China really doesn’t start to take off until the 1980s-1990s, putting the nation right in the natural zone for democratization four decades later.

But that’s where the rise of Xi has retarded the entire trajectory: he senses the historical trajectory and moment, and, true to his formative years, he reaches for a Cultural Revolution-lite, or one enforced largely through cyber means — Xi’s omniveillant society being the Cultural Revolution digitalized.

This is Xi believing the Party can have its cake (development) and eat it too (stave off democratization). The problem is, the global economy can’t live with that outcome of China continuing to get rich by export-driven growth while not fully unleashing — and addressing — mass domestic consumption that, in Xi’s worldview, represents the death of Party control and socialism in general. Because the more people get what they want, the more they want what they don’t have — political freedom to go with that economic freedom.

So Xi seeks to use one (economic consumption) to police the other (political participation). The social credit scoring system is the tip of that iceberg: getting individuals to police themselves politically by tying access to economic consumption to approved (and constantly tracked) social behaviors.

Externally, Xi wants China to stay in extreme export-driven-growth mode — an outcome the world cannot accept.

Why?

China cashed in its demographic dividend and has moved up the production chain and now it’s time for others to follow in its wake — like India. But Xi’s strategy denies that graduating dynamic — just like his decision to make himself president-for-life denies the graduating dynamics of what should be the Sixth Generation of leaders in China (Mao 1, Deng 2, Jiang 3, Hu 4, Xi 5, ??? 6).

In short, China isn’t moving along like it should, sort of constipating the system as a result.

Xi’s choice cannot succeed: it will cost too much of the rest of the world too much in terms of economic and — ultimately — political advance.

Many experts say the world is de-globalizing since 2008 when it isn’t. While the goods trade has flatlined globally, that’s not deglobalization per se. There’s no logic that says we have to have the longest, most complex supply chains possible to be advancing in terms of globalization. That just doesn’t make sense.

There are optimum levels in all things human and we reached a lot of those in Peak Globalization (1990-2008). Now, we’re on to something else, like the digitalization of globalization, China’s hoped-for evolution, rise of India, later the rise of Africa. The train must move on, but Xi is holding it up, yielding this sort of strange situation described by the Financial Times like this:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thomas P.M. Barnett’s Global Throughlines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.