In general and reductionist terms, climate change dehumidifies Earth’s surface while humidifying the atmosphere. This sets in motion great and continuing transfers of water from certain world regions to others. We begin to recognize the power of these transfers in the dynamics of atmospheric rivers, which have the capacity to transform the environment of regions that suffer them at high frequency/intensity, creating whiplash effects that leave the region in question that much more vulnerable to extreme climate events in general (like Los Angeles recently with the fires).

Two recent articles/posts where I explored this dynamic:

POPULAR SCIENCE: Greenland’s lakes are getting uglier—and fast

UCLA: Floods, droughts, then fires: Hydroclimate whiplash is speeding up globally

Warmer temperatures trigger more evaporation from water and land surfaces. Because warmer air holds more moisture, the concentration of water vapor increases, in turn, intensifying the water cycle.

In the simplest terms, wet regions grow wetter and dry regions become drier. Those wet regions, on average, lie to the north (and higher latitudes in general), while those dry regions lie to the south (and lower latitudes in general).

This disparity in environmental risk, if you will, will come to define geo-political risk this century more than any other factor you can name.

Why?

Because, unlike the case of technological advance, which invariably spreads out globally, this disparity is geographically locked-in for the rest of this century — to say the least. Not really much of anything we do in the short term will alter this emerging geo-strategic reality and the migratory pressures already in evidence (species moving poleward and upward in elevation all over the planet).

Thus, water increasingly becomes an ordering principle, particularly in its relationship to energy (or, more agnostically, power [typically, electricity]). Sufficient and trusted access to some combination of the two defines habitability in this world — at the low end of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. At the higher end, it determines economic power in terms of sheer capacity-building — e.g., the enormous power and water requirements associated with chip production or data centers. Ultimately, it should become the basis for currency value by more effectively signaling an economy’s viability than such far-more-detached measures (mere possession of minerals, hydrocarbons).

[Recall the origins of the word salary: Roman soldiers paid partially in salt rations — hence the phrase, being worth one’s salt.]

If salt (something you dig out of the ground) was used as currency in ancient times, along with precious metals (gold, silver), only to be superseded eventually by oil (petrodollars), then water (its sustainable management and manipulation) logically steps into that vaunted status this century.

And yeah, that inevitability favors the United States.

And no, you don’t have to “believe” in climate change to recognize this growing primacy. Debating cause has given way to debating adaptation to effects. Don’t believe me? Keep an eye on your homeowners insurance policy as the “natural” disasters keep piling up.

In 1793 the firm of Almy, Brown and Slater replaced their experimental workshop with a new mill. Known as the Slater Mill, it was the first water powered textile mill in America. The original mill was six windows wide and two and ½ stories tall.

This is not a new phenomenon for humans, who long ago learned about the primacy of that combination (water and power) in determining where industry could thrive. In our modern world, we just sort of forgot how primal that combination is. Having built cities in the desert, and drawn down our groundwater supplies recklessly, and consumed entire river flows, and air-conditioned our entire existence … we lost our respect for, and awareness of, that water+power primacy.

Atmospheric rivers represent that primacy in a climate-changed world. They grow stronger and more frequent and, like so much in our natural environment today, they are shifting poleward over time. Meanwhile, in arid and semi-arid regions, atmospheric moisture has not increased as expected with climate warming, leading to an increase in vapor pressure deficit. This can lead to wildfires and ecosystem stress.

VAPOR PRESSURE DEFICIT: the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and the maximum amount of moisture the air can hold at a given temperature, thus indicating how much "drying power" the air has.

As the recent events in West Greenland (cited above) proved, a shift in atmospheric rivers can have big effects on local climates — in some instances transforming them permanently in a climatic heartbeat (few months).

Atmospheric rivers impact regions differently, generating benefits and risks. They can be crucial for replenishing water supplies (half of California’s annual rainfall), but they also pose threats of flooding, landslides, and infrastructure damage.

In general, the south and west of the US will become ever more subject to atmospheric rivers, amidst their more general migration toward the poles. This will lead to outcomes such as atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska, while their absence generates longer droughts for areas like California and Brazil’s Amazon region that depend on them for rainfall.

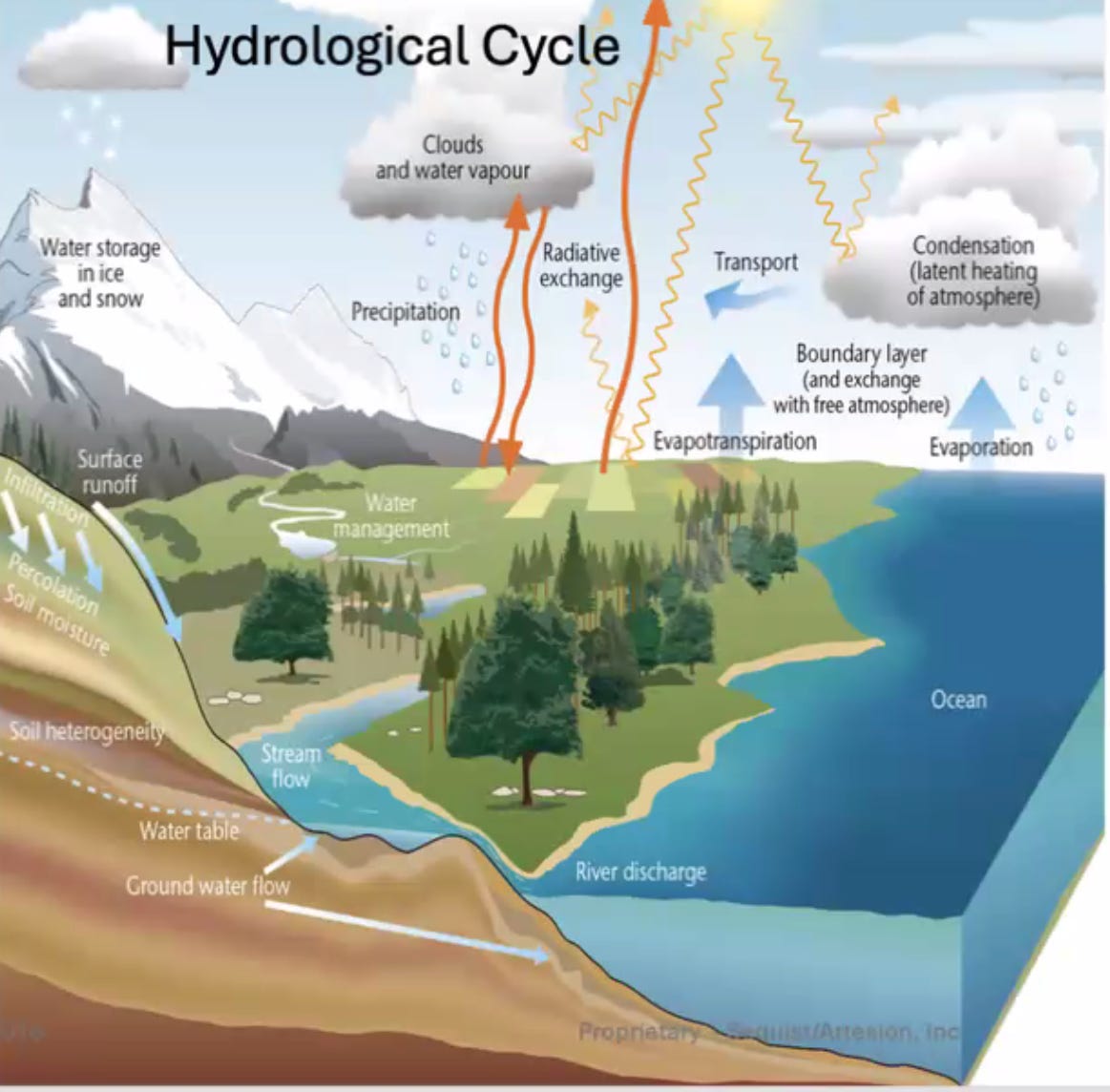

Back to the hydrological cycle:

Humans, I would argue, have grown too used to viewing this cycle primarily in horizontal terms, or once precipitation hits the surface and flows along our various groundwater vectors. We used to be more rain-centric, but over time we became more well-centric — technology finding a way. As with gold and oil, we grew accustomed to viewing water as something that comes out of the ground — almost without limits (untrue, of course).

What climate change does is reorient us toward that vertical portion of the cycle — you know, the what goes up must come down part.

This is where CEO and Founder of Artesion (product and services company offering breakthrough water-management technologies), Karen Fleckner, enters my career picture and the world at large.

Karen’s vision starts with an AI/ML/IoT/edge computing/pervasively sensored/big data approach to managing the nexus of water and power. On the power side, Artesion is agnostic, but on the water side, the firm ultimately seeks to tap that vertical portion of the water cycle for “vector-free” or “green” water.

Atmospheric rivers are like "rivers in the sky" that carry substantial amounts of water vapor from one area to another. They are concentrated channels of moisture in the atmosphere that play a vital role in the Earth’s hydrological cycle. These airborne corridors of water vapor transport water from the tropics to higher latitudes. An average atmospheric river is about 1,200 miles long, 300 miles wide, and nearly two miles deep. Strong atmospheric rivers can move moisture at 15 times the discharge rate of the Mississippi River.

In other words, all that moisture being shoved up into the atmosphere? It’s there for the taking/redirecting/managing.

One key component of that technology approach, known as atmospheric water generation (AWG), is well established and out there at a wide variety of scales. Basically, the industrial version is like a giant air conditioner (HVAC) that is optimized and attuned to dehumidifying the atmosphere up to a certain altitude (or within what Karens calls the Near Lower Atmosphere [NLA] between Earth’s surface and, say, about 30,000 feet) to produce potable water (condensation).

Karen’s vision is a practical one: adapting to a world facing greater disparities in humidity and effectively arbitraging that risk latitudinally through the creation of municipal/regional/hemispheric water+power networks tied to existing or new power networks.

Think about how we today manage and trade electrical power across North America (in deep collaboration with hydro-powered Canada, mind you) and imagine adding water management to that dynamic. Then consider adding nuclear power capable of generating potable water via desalination of seawater.

Now, you’re starting to see the bigger picture.

A water+power equivalent of the US interstate highway system is not a new concept. It was first broached decades ago:

The North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWPA or NAWAPA; also referred to as NAWAPTA, after the proposed governing body, the North American Water and Power Treaty Authority) was a proposed continental water management scheme conceived in the 1950s by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The planners envisioned diverting water from some rivers in Alaska south through Canada via the Rocky Mountain Trench and other routes to the US and would involve 369 separate construction projects. The water would enter the US in northern Montana. There it would be diverted to the headwaters of rivers such as the Colorado River and the Yellowstone River. Implementation of NAWAPA has not been seriously considered since the 1970s, due to the array of environmental, economic and diplomatic issues raised by the proposal.

Up to this point in history, such “friction” was sufficient to block any such ambition. As for today and going forward … expect the “force” of this logic to expand exponentially because this is the essence of socializing the latitudinal risk associated with climate change.

In other words, what was inconceivable then can easily become inevitable with enough pain and time.

If, as we’re coming to realize, atmospheric rivers can increasingly alter or even transform local and regional climate conditions, then tapping and/or managing those rivers becomes both a defensive reaction (ensuring supply) and an opportunity to be exploited (surge production and storage).

To me, this is radical acceptance of the highest order:

Human activity has changed the world’s climate.That changing climate creates disparities in water wealth.

[If bullets 1 and 2 add up to zero or less for you, then go straight to the one immediately below.]

Humans must adapt to increasingly chaotic climate by learning how to better manage the water+power nexus that, across the century, comes to define economic growth — not to mention habitability.

By achieving that management potential, humans begin to modulate and control the weather on a local/regional scale (yes, we will crawl before we walk — much less run).

That capability can, over time, be marketed, allowing for the socialization of water risk — largely along latitudinal lines. This is a MUST for national security this century because the lack of such risk management will trigger all manner of threats to social stability and economic vitality. [And, yeah, this is another reason why Canada matters to the US.]

Such successful management and optimization of the water+power nexus is, logically over time, financialized (made trade-able).

Ultimately, that successful management should become the basis for currency valuation, replacing such predecessors as salt, gold, silver, and hydrocarbons. In a world undergoing massive water-cycle change forcing unprecedented water+power management, citing water as a basis for valuing currency makes as much or more sense than your ability to crunch mathematical equations — right?

The biggest picture/payoff: such technology-driven management of the water+power nexus on a regional or even hemispheric basis represents a sort of miniature terraforming that logically prepares us for such efforts on grander scales in a space-faring future. [Years ago Elon Musk asked NASA to put a hothouse on Mars for testing purposes … hey! Elon! We’ve can gin up such testing sites all over North America!]

So let’s think this thing through a bit further, like along the lines of rules emerging.

Think about such a future: We have a UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that’s focused more on the horizontal portion of the water cycle. What we will need over time is something similar for the vertical portion — a UN Convention on the Law of the Atmosphere, if you will, or something along such lines.

From a key report entitled: Getting law to work for the water-cycle

Adapting law to reality

The global water cycle entails the circulation of water in its liquid, solid, and vapor phases as it moves through the atmosphere, the land, and the rivers, lakes, and oceans. It consists of three major processes: evaporation, condensation, and precipitation and this cycle is fundamental for securing access to freshwater.

The authors point out that current governance architecture only accounts for some of the global hydrological cycle dynamics and mainly target blue water, i.e. water that comes from the ground, from a river, a lake or a dam, not green water, that comes from natural precipitation.

Should America pioneer that new ruleset ASAP?

Yup.

Should it then seek to export that ruleset to the rest of the world?

Absolutely.

That is a pattern of behavior we have exhibited many times in the past (think about nuclear technology, the original internet, GPS, drones, AI, etc.).

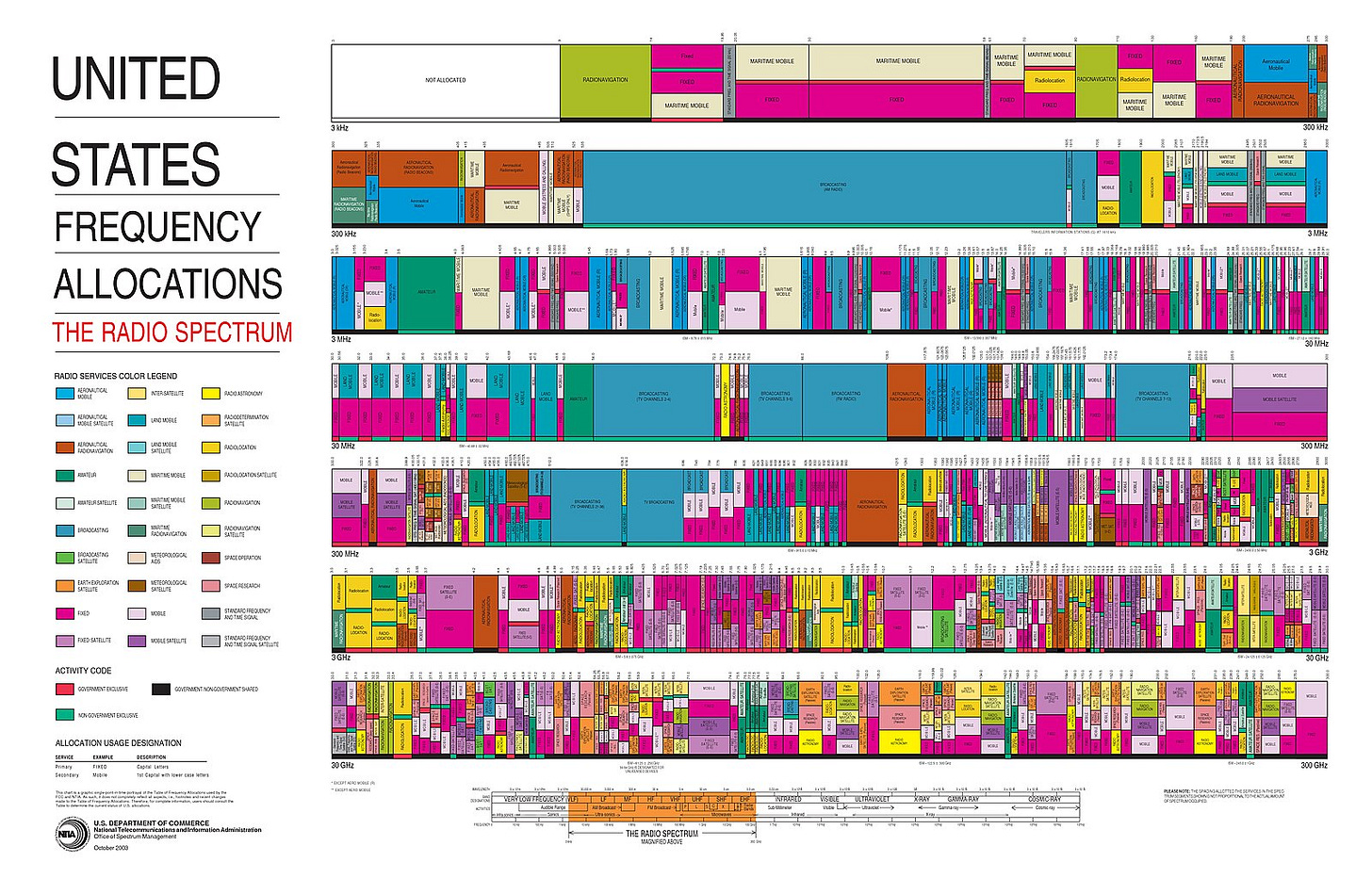

Where can we also look for precedents for, and guides to, this future?

Think about how we divided up and regulated the wireless spectrum, for example.

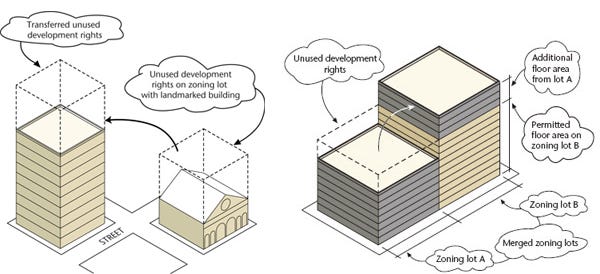

Think about how New York City manages development through “air rights.”

Consider the history of “air sovereignty.”

When I was first exposed to Karen’s technologies and vision a few months ago, my reaction was, this is so much bigger than what you’re talking about!

I have long stated that such a statement is essentially the PERFECT RESPONSE to the kernels of grand strategic thinking.

I think Karen is possibly the smartest person I have ever met. I know she has a grand strategic mind — no matter what lower and more practical levels she works in the near and medium-term. She has shocked my system/worldview by demonstrating how a thinker and entrepreneur can help trigger structural change on a grand scale in the service of this country (and humanity) this century.

And that’s why I agreed to become a Senior Strategic Advisor to her company, Artesion.

However you feel about Trump and the multitude of transformational revolutions he’s got cooking, we live in a time in which new circumstances and realities demand new approaches and models. I have bumped into this level of genius in the past (Steve DeAngelis of Enterra Solutions, where I worked in the firm’s formative years and with whom I continue to collaborate) and I never let go.

I intend to do the same with Karen and Artesion.

Companies like Enterra and Artesion and — most recently for me — Throughline are just too crucial to the solution-set that is a Second American Century for someone like me to be restricted solely to oppositional stances vis-a-vis Trump 2.0. Amidst destruction there are plenty of opportunities to build.

Big visions yielding big technologies forging big solutions to existential challenges.

With this much play in the system right now, all responsible parties must engage in pathfinding. There is simply too much at stake to merely stand by.

This is what gets me up in the morning and keeps me going all day long.